Review: Kate Bornstein’s On Men, Women and the Rest of Us at Manchester’s Queer Contact Festival

February 26, 2016

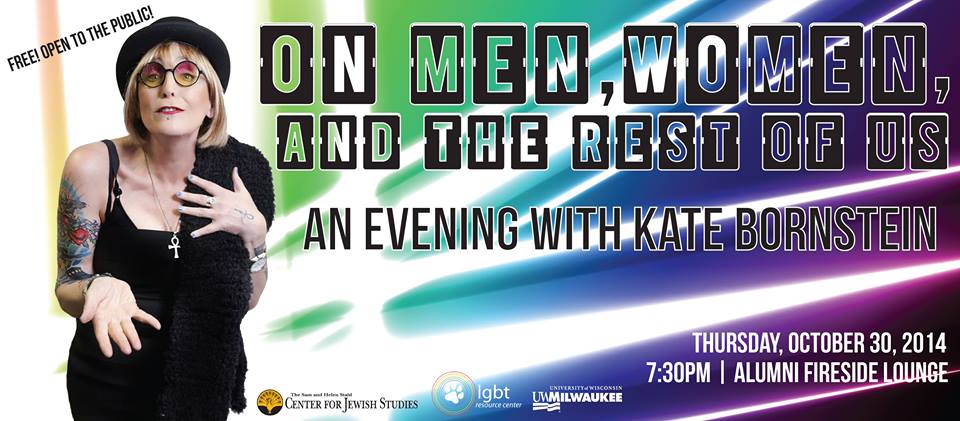

As part of this year’s Queer Contact Festival, I head to Manchester’s Contact Theatre to see transgender activist, performer and self-appointed ‘advocate for teens, freaks and other outlaws’ Kate Bornstein. The piece, ‘On Men, Women and the Rest of Us’, kicks off with thundering, almost militaristic music, and I wonder what I’ve let myself in for. But Kate unassumingly shuffles onto the stage; elegant, wise, softly spoken and a little bit naughty – in other words, immediately loveable.

This piece was different from others I saw as part of the festival as rather than being a show in any clear-cut sense of the word, the evening felt more like a cosy evening in catching up with a friend, sharing anecdotes, personal trials and tribulations and putting the world to rights. Her work is described as spoken word but it lacks, for better or for worse, the characteristic lyrical modulations and urban punch usually associated with the genre. Bornstein’s style is closer to story-telling, a perhaps safer aesthetic through being less at risk of sounding artificial. Kate is sweet, sincere and candid, and totally at ease, sitting back on a chair as her audience gathers to listen to her tales.

Having been involved in activism and performance for more than a quarter of a century, Bornstein’s piece spans two generations, telling of a world that is finally showing signs of changing. She describes the misunderstanding and suspicion surrounding LGBTQ identities in her youth, experienced herself all too often as one of very few openly transsexual (now more commonly termed ‘transgender) individuals living in her area at the time. Even when the New York Times was set to publish one of her pieces, they harboured concerns about including the term ‘transgender movement’, for fear it would equate to acknowledging that one actually existed. While there remains much to be done, we are finally seeing shifts into a time where the need for the respect, rights and representation of LGBTQ identities is being established as a baseline point on which we need to build.

The defining theme of Kate’s work has to be her the struggle to establish a definitive identity. Selecting ways to define herself from her ‘inventory of identities’, she attempts to navigate a world divided into male and female, despite falling somewhere in the middle. While this sometimes means choosing the path of least resistance and simply picking one, some areas of her life provide the possibility of multiple and shifting identities. Her mother – initially confused and upset by Kate’s coming out, sarcastically referring to Kate as ‘my son, the lesbian’ – ultimately gives Kate her most poignant acceptance. Morphine-addled and on her death bed, her mothers demands ‘Who are you?’, and, in response to Kate’s ‘proffered selection of whos.’ replies, ‘That’s good. I didn’t want to lose any of you, ever’.

It is perhaps this recognition of the possibility of multiple identities which has led Kate to interrogate the usefulness of notions of identity of any kind. After all, she says, the cells in our bodies are totally replaced every seven years with new ones, a conceptual shedding of one’s skin and identity. How can we claim to be any one thing despite physically having nothing in common with ourselves seven years ago? After spending thirty-seven years male and eight female, Bornstein has concluded that neither is really worth the trouble. Identities, as Kate sees them, are addictions: one of many manifestations of the ego which must be overcome if we are to feel truly peaceful.

As much as Bornstein essentially rejects over-identification with one gender or another, her work nonetheless powerfully critiques society-at-large’s expectations of those who do identify as women. Discussing her first foray into voice-coaching with a view to learning to speak like a woman, she describes how she was instructed to modulate her tone, be breathier, smile more (because ‘women always smile when they talk’) and add tagging questions after her assertions to convey self-doubt and humility. Rejecting this, she took a friend’s advice and listened to Laurie Anderson on repeat until she had a voice which felt right. Clearly, her mother’s experience of hearing male members of the family repeating, ‘Thank God I was not born a woman!’ impacted on the kind of woman Kate was going to be. Strong, funny and kind – Kate in turn is the perfect example of what any idol, male or female, should be.

As we leave the theatre, each member of the audiences receives a Get Out of Hell Free Card, which reads: ‘Do whatever you need or want to do in order to make life worth living. Love who and how you want to love. Just don’t be mean. Should you get sent to Hell for doing something that isn’t mean to someone, I’ll do your time in Hell for you, kiss kiss – Kate’. There’s no arguing with that. Kate, you’ve got yourself a deal.

Comments