Khanyisile Mbongwa is a curator whose practice centres on ‘Curing and Care’. For the 12th edition of the Liverpool Biennial, the Cape Town-based curator will focus her curatorial concerns on Liverpool, a city which, during the eighteenth century, was referred to as ‘the second city of the British Empire’ due to its pivotal role in the trade of enslaved people.

‘uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things‘ will interrogate the history and temperament of Liverpool. Through emancipatory practices, joy and play, it will explore ‘catastrophe and aliveness’, acknowledging the past, centering repair and imagining a potential future. I met with Mbongwa, to talk about the theme of this year’s Biennial, her curatorial practice and the potential legacy her programme could leave.

Lubaina Himid, Between the Two my Heart is Balanced, 1991. © Lubaina Himid, Courtesy of the artist and Hollybush Gardens.

I began by asking about the significance of the title. ‘uMoya’ is an isiZulu word which means ‘spirit, breath, air, climate and wind’. Mbongwa explains its significance: “It was important for me to include my mother tongue when thinking through what the Biennial could be. (It is) a first encounter with both the wound and its possibility to heal. I think language is an important part of what is lost, stolen and suppressed when people are colonised.”

The impact of colonialism on indigenous languages has, in some cases, caused their extinction and was an important tool to eradicate indigenous cultures. “It was important for me to have in the title, an ontology conversation around language and what happens to the tongue when we are colonised and enslaved, the violence of that and how some people can never return to a mother tongue.”

The elemental nature of wind and its role in Liverpool’s past is important too: “The force of the wind is what propelled the imagination to live up to what the city did with enslavement. I’m in deep conversation with the wind here. It’s very difficult to look at a natural resource and think of it as part and parcel. I’m asking questions of the wind – Why did you assist? Why have you invited me here? Why are you making sure that I can feel you? What do you want to show me?”

Katy’taya Catitu Tayassu, TransFORMEactions Dreams and Regenerations, 2022.

The wound, created by colonialism, requires Black people and people of colour to hold both the trauma of the experience and the violence of the coloniser.“We are demanded by the world to hold intergenerational trauma based on seeing ourselves completely and utterly through violence and being violated and conquered. We are asked to sit in the trauma and the violence. Not only do we hold our own trauma and violence but also hold the violence of the coloniser, because if we hold it they don’t have to”.

By asking simple, straightforward questions – How did you get there? What happened? How did it happen? How does this continue to manifest? What is the potential to heal? How do we heal? – by getting back to basics and relating it to the body, Mbongwa can bring the legacy of enslavement close enough to start a conversation. She asks: “How can we create space through these creative and artistic interventions to sit alongside the wound and ask it what it needs and question what is my role in this?” The second part of the title – ‘The Sacred Return of Lost Things’ – aims to walk the line between ‘catastrophe and aliveness’ and asks how we can “hold or speak about these painful encounters… how do we at the same time marvel in our aliveness?”. Mbongwa does not only open up and examine this wound, she celebrates ‘aliveness’.

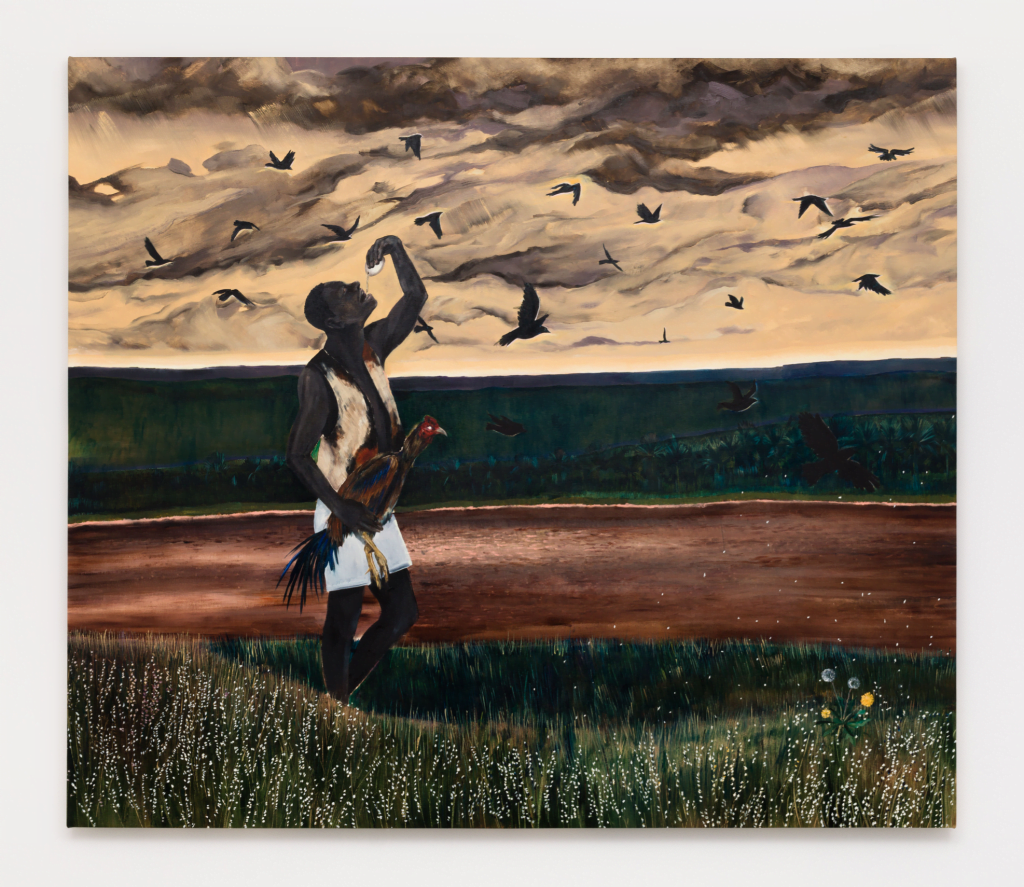

Antonio Obá, Alvorada, Música Incidental Black Bird, 2020.

It is an ambitious project. However, Mbongwa’s early experience working with Gugulective, a collective formed in 2006 of creatives from Gugulethu, the township she grew up in, instilled a collaborative approach to her curation. She is able to curate with a heightened sense of self-awareness, enabling her to hold space for conversations to happen through the work.

She highlights, “Working in a collective, where there were so many tensions, made me self-aware. The collective challenges your ideas and your perspective. There were eight of us so when you proposed something, you have seven other voices challenging you. I think that has equipped me to listen. When I invite artists, I’m interested in the conversation that emerges between myself, the artists and the work. In a collective the author is dead, so we all become authors.”

David Aguacheiro, Take Away, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. (Credits: Tina Krüger)

Each Biennial leaves a legacy, so I asked Khanyisile what she would like her personal and professional legacy to be.

“Personally, I think for my kids to look back at this moment and say ‘She was brave enough to speak and communicate what she felt inside’. For my ancestors, to say ‘thank you for making it possible for us to be present here, to look at our wounds and see how we can heal them’. Professionally, to leave behind ‘Care’ as a creative practice.”

I ask what she wants the public to take from the Biennial.

“The desire I have is to create a safe space to face yourself and your ancestors. To face what has actually happened here in Liverpool and the role of this city and country in some of the devastation of the world. I believe that when we truly take accountability, we are one step closer to actually opening up the wound. We cannot open the wound if we are not ready to ask ourselves – what happened here and how am I tied to what happened?”

The Biennial is the biggest project of Mbongwa’s career to date. She dedicates each project she works on and the Biennial is dedicated to a number of important people in her life – Palesa Ndlovukazi Sibiya, friend and soulmate, who died on 26 January 2022, the day Mbongwa was announced as curator for the Biennial. It is also dedicated to the community that makes it possible for her to be an international curator with a young child, maintaining the line between catastrophe and aliveness, the ancestral and celestial:

“That line where we have experienced so much but we are insistent on being alive. To imagine ourselves into existence when we yearn to be alive, not as a response to violence, not as an explanation of why we’re here, just be. Full stop.”

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: art, artists, biennial, Cape Town, colonialism, curation, curator, legacy, liverpool, South Africa

Comments