It’s impossible to pinpoint when glass began. There is the young rock, Obsidian – a pitch-black naturally occurring glass of just 20 million years old. It was made into sharp cutting tools in the Stone Age. There are also fulgurites – insane zigzagging statues protruding out of sand or rock, created when lightning fuses with the earth. The Roman philosopher Pliny suggests that Phoenician merchants made glass in modern-day Syria around five thousand years ago. But archaeological evidence suggests that human production of glass began in Eastern Mesopotamia and Egypt around 1500 years later.

Over the centuries glass has become woven into human life – as tools, windows, jewellery, glasses, and other vessels. But its existence is a constant paradox: it’s at once common and luxurious, familiar and otherworldly, durable and fragile. Glass is ever-present and a staple, but also an afterthought, a stranger.

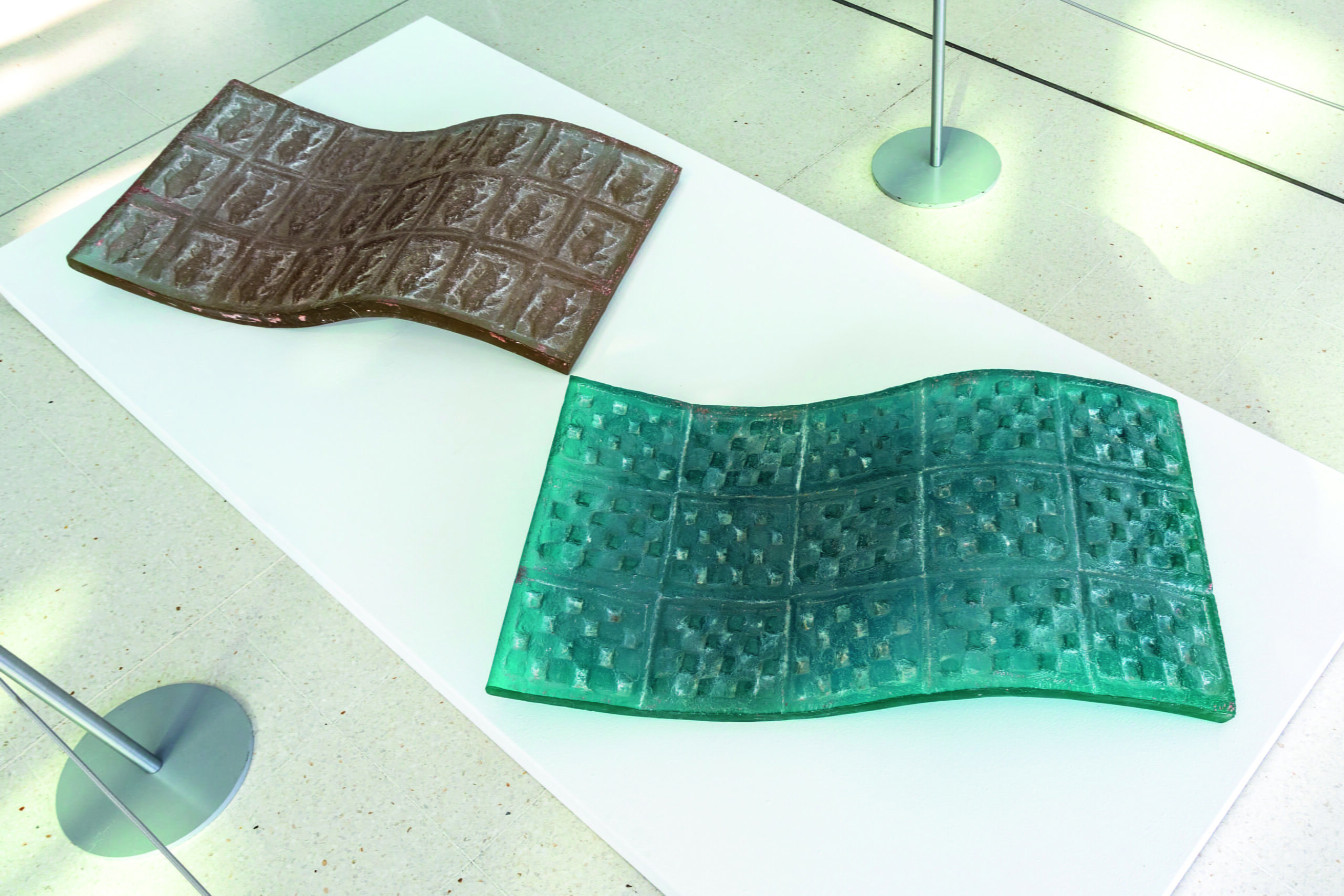

Installation views of ‘A State of Matter: Modern and Contemporary Glass Sculpture’ on display at the Henry Moore Institute 18th February-5th June 2022 (Credit: Rob Harris)

Its inspection, then, in a new exhibition at Leeds’ Henry Moore Foundation comes as a real treat. In categories of solid, liquid and gas, audiences are reminded of the ancient substance’s capabilities beyond its function, as it is morphed into sculptures and displayed in its molten form on film.

Curated by Dr Clare O’Dowd, ‘A State of Matter: Modern and Contemporary Glass Sculpture’ first and foremost displays a range of enigmatic glass objects – from a sculpture of a malaria virus to balancing spheres to twisted figures, to an almost two-dimensional wine bottle with an accompanying fallen glass and pool of liquid.

But by being presented with these sculptures, the audience is asked to change the way it thinks about glass. British-Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum’s piece, for example, is of red glass globules trapped in compartments in a rectangle silver cage. The blobs are anything but glass as usual. Perhaps organs or some other kind of living organism, their location inside a cage of clean, straight lines – each padlocked into their cell – makes their existence as glass objects all the more jarring.

Similarly, the exhibition displays an uncomfortable sculpture by American artist Claire Falkenstein. What was once a recognisable green glass bottle has been heated and contorted to become an elongated frozen mass, surrounded by ironized metal rods like a crown of thorns. There is a liquid in the bottle now – also melted – that looks like a liver has burst and splattered inside a translucent stomach.

This is glass as we have not seen it before. Other artists in the exhibition included the De La Torre Brothers, who use glass to explore bicultural identities and the Mexican American immigrant experience, Erwin Eisch, one of the 20th century’s most prominent glassmakers, and Czech artist Alena Matějka who makes thick 30kg ‘carpets’ from glass. The carpets are covered in historical patterns and remind the audience that glass does not need to be flimsy – in fact, Matějka’s largest carpet is the heaviest piece of kiln-formed cast glass ever made.

Alena Matějka Magic Carpet 2004. Courtesy National Glass Centre (Credit: David Williams)

Whether in the sculpture category of solid, liquid or ‘gas’ (blown), each of the pieces selected for the exhibition introduces audiences to new dimensions of glass. In many cases, its new state can best be described as body-like – such as the red organs and burst liver. But why should this natural material provoke such physical images?

Emma Woffenden, an innovative mixed-media sculptor who works in Britain and France explains that humans and glass share some similar attributes.

“There are more obvious ones, soft-looking things can look like human organs, runny glass can evoke body fluids, early-stage glass shapes can look phallic or breast-like, maybe these are the first ideas thought when artists enter the glass studio and see glass blowing.

Then there are qualities like fragility, emptiness, sensuality, heaviness, light and shadow metaphors we equate with our psyche. These are starting points that can become interesting.”

It is this power that allows glass to retain its enigmatic profile. Glass can, of course, be sensual – yet how? It is made of sand, soda ash and limestone, heated into molten matter.

Woffenden’s own work deals with themes of myth, archetypes, and the psyche. Although employing a wide range of techniques she is best known for her glasswork, where androgynous figures are fixed into unfamiliar poses: sometimes comedic, sometimes unsettling. Her piece ‘Creature’, has a tongue, or beak, long legs and genitalia. Although cold and otherworldly, the glass nevertheless provokes intense feelings of the body.

Emma Woffenden Creature 2015– 2018. Courtesy National Glass Centre (Credit: David Williams)

“Sculpting glass is made with the body, where it requires a sort of choreography, mental strategy, and focus – all aspects of glassmaking require immense focus because it is dangerously hot, and when it is cold, it is dangerously sharp. Glass has a skin with a sense of fluidity and depth below its surface. It is all very human,” adds Woffenden.

The exhibition also brings a vividity to glass: if you haven’t thought much about the material before, you will on your walk home. Suddenly you notice that glass is absolutely everywhere. It is shards of a broken beer bottle on the pavement, it’s a black lacquer sheen across the tower block, it’s misty on the car that passes you, and wet turquoise panes on the pub door.

This surrounding quality of glass interests Petr Stanicky, one of the exhibitions’ sixteen artists. Stanicky is the Head of Glass at Tomas Bata University in Zlín, Czech Republic, and has exhibited his work around the world. More than ever, he makes spatial compositions and site-specific installations, dealing with questions around space, light and reflection.

“Glass attracts me more and more because it has the ability to constantly change and supplement the needs of people in this world. The greatest example of this can be seen in our cities,” explains Stanicky. “Windows mediate the world around us.”

In the exhibition Stanicky’s piece, ‘Mirror-Mondeo Bite’ combines a car window with a blown globule of silver glass. The unfamiliar ‘liquid’ glass looks like it is eating or attacking the familiar car window. Why should one version of the glass produce such an effect that it becomes almost animated, while the car window lies flat – cold, still? Is the globule anthropomorphised simply because it is unfamiliar?

Petr Stanicky Mirror 2014. Courtesy National Glass Centre (Credit: David Williams)

“The object connects the ordinary with the imaginative, but at the same time, the solid with the fragile, and organic with the industrial. These are properties that are unique to glass and fascinating to me,” says Stanicky.

“I’m not sure if it’s alive, but I can pretend it is and it’s definitely liquid. It is actually referred to as a chilled liquid. It does not have a solid crystal lattice. It is fragile and strong at the same time, it is solid, but it can be bent, inflated, blown, melted, and cut like a stone. It is also similarly stable (for centuries).”

In the exhibition, there is a sentient element to the glass on display, and this begins to draw in audiences as much as it has the artists. While glass is absolutely historical and ancient, here in ‘A State of Matter’ it feels modern – futuristic even, probably in part to seeing glass in shapes and sculptures that are unusual and uncharacteristic.

Emma Woffenden sums it up nicely: “I enjoy the history, the community, the sensuality, along with the futuristic look and emptiness of the medium. Glass making feels limitless, it is obsessively challenging.”

***

The Henry Moore Foundation was founded in 1977 by the artist and his family. Henry Moore remains one of the most celebrated British artists of the last century and his sculptures can be found around the world including in Hawaii, New York, Jerusalem, Paris, Tehran and New Delhi.

Henry Moore was born in Yorkshire in 1898. He served in the First World War, and trained to become a teacher but then retrained at Leeds School of Art and then the Royal College of Art.

‘A State of Matter’ marks the United Nations International Year of Glass 2022. The exhibition runs until 5 June 2022.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: art, artist, contemporary, exhibition, glass, glass blowing, liverpool, molten, sculpture, Studio, vivid

Comments