Robert Motherwell’s ‘Wall Painting No III’, 1953.

On the one hand, an exhibition created jointly by an art historian and an experienced curator could provide the best of both worlds: a smartly organised and flowing layout, with texts and underlying ideas that really get beneath the surface of a complex group of artists. On the other hand, you could end up with a slightly confused and jumbled show that struggles to smooth over the pull and push of two curators who perhaps did not entirely agree on what they were trying to achieve with this blockbuster.

In the first room of the exhibition, we are introduced to the big idea behind it all: a chance to see, for the first time in decades, a show that situates the whole gamut of so-called Abstract Expressionist artists together in one place. One man shows for Pollock, De Kooning or Rothko you may have seen, but this time we will have the pleasure of viewing this disparate group of artists as a whole, as representatives of a critical time in US history, the moment when the first truly American art movement was born. That is what’s special, or could have been, if the show’s curators had stuck to their guns.

Jackson Pollock’s ‘Blue Poles’, 1952.

Instead, some artists—the Pollocks, De Koonings and Clyfford Stills of this world—are given whole rooms to themselves, which, says Anfam on the audio guide, we will recognise as having subtly different wall colours. Genius. The Krasners, Mitchells, Motherwells, and Tobeys (and many more) are, on the other hand, crammed in together in weakly themed rooms. One in particular, ‘Works on Paper and Photography’, felt especially like ‘other things we had left over and didn’t know where to put’. Sketches by Pollock and ink drawings by Kline, which might have sat nicely alongside larger works by these artists and informed the viewer of their processes, are amassed together in one room towards the end of the exhibition where gallery fatigue is already setting in.

The wall texts in this exhibition are more intellectual than you might usually see, and in some ways this is a good thing—there’s nothing quite so annoying as being patronized by vinyl lettering. But we are missing some of the basics about the movement, if it can even be called a movement, and the art history-speak goes a little far, with the voice of the co-curator coming through too prominently. Describing Pollock’s fatal car crash as “quasi-suicidal” is a flippancy too far, especially as the comment is not then explained or justified, and reducing Krasner’s epic ‘The Eye is the First Circle’ to a canvas which “ranks as perhaps the most memorable single tribute to Pollock” does the artist a disservice. It was painted several years after her husband’s death, an event that did of course greatly affect Krasner’s art, but shouldn’t so exclusively inform our view of her subsequent work.

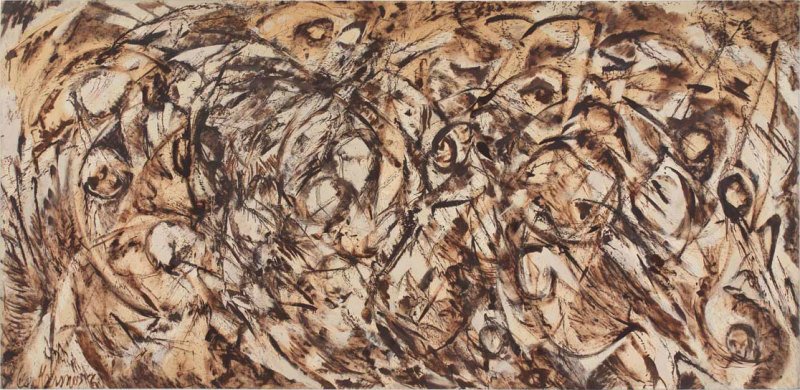

Lee Krasner’s

‘The Eye is the First Circle’, 1960.

In case you were interested in knowing a little more about Krasner as an artist in her own right, the sweeping burnt umber tones in this piece are a direct result of the artist’s insomnia. At the time, she was painting a lot at night, and since she didn’t “like to deal with color in artificial light”, she chose to work solely in these brown hues, producing a whole show of similarly coloured works for Howard Wise in 1962.

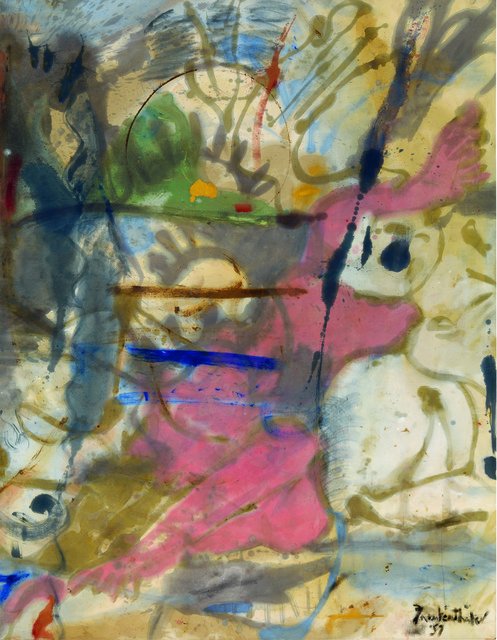

Female artists are predictably thin on the ground, and do feel like a bit of an afterthought, but there are some stunning works every now and then. Joan Mitchell’s four-canvas ‘Salut Tom’ is a real jaw dropper, heavily laced with scents of Monet and the Vétheuil landscape where she lived and worked. A work by Helen Frankenthaler is featured in the ‘Gesture as Colour’ room, and even though her Abstract Expressionist credentials are debatable, it’s a strong piece, a departure from the brighter, more delicate floral canvases that are perhaps more widely known.

Helen Frankenthaler’s ‘Europa, 1957.

Titled Europa, it is a semi-figurative work, with discernable pink, fleshy, limbs in a tousled and grubby milieu that suggests the mythical rape narrative of the eponymous character. It showcases Frankenthaler’s famous ‘soak stain’ technique and stands out as noticeably different from the works around it, helping us see that, though the core abstract expressionists are hard to pin down and define, here we still have something that doesn’t quite align with their works.

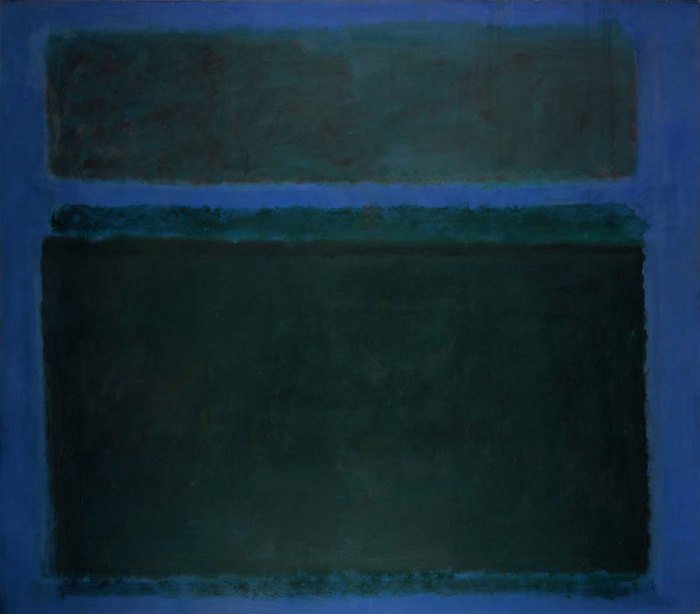

Of the artists who do have rooms of their own, Clyfford Still’s is the most successful. His huge works, with their earthquake fractures and jagged rips of paint, look well side by side in their unrelenting verticality, giving a real sense of the groundbreaking genius of this outsider. The Rothko room, though, has the opposite effect. The curators have chosen the vestibule space in an attempt to re-create the low-lit spiritual atmosphere of Rothko’s famous Chapel. It does not work. The pieces have jarringly different colour schemes, and that encircling calm evoked by the repetition of dark muted colours in his Chapel is simply impossible to achieve with greens, yellows, reds, and blues all competing to be seen in the low light.

Mark Rothko’s ‘No. 15’, 1957.

It’s a shame this exhibition hasn’t really come off. It was no doubt very expensive and difficult to organize, and there are some real gems in there for sure. But a cohesive, well-narrated show it is not. There is a distinct lack of focus, and for such a contrasting group of painters, who all have such idiosyncratic styles, this proves fatal. In some rooms we are looking at a particular artist, in others technique, medium, time period, then back to an individual again. If you thought Abstract Expressionism a confusing notion before you entered the galleries, don’t expect much clarity once you’ve left.

Abstract Expressionism runs at the Royal Academy until 2 January 2017.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: Frankenthaler, Krasner, Motherwell, Pollock, Rothko, Royal Academy

Comments