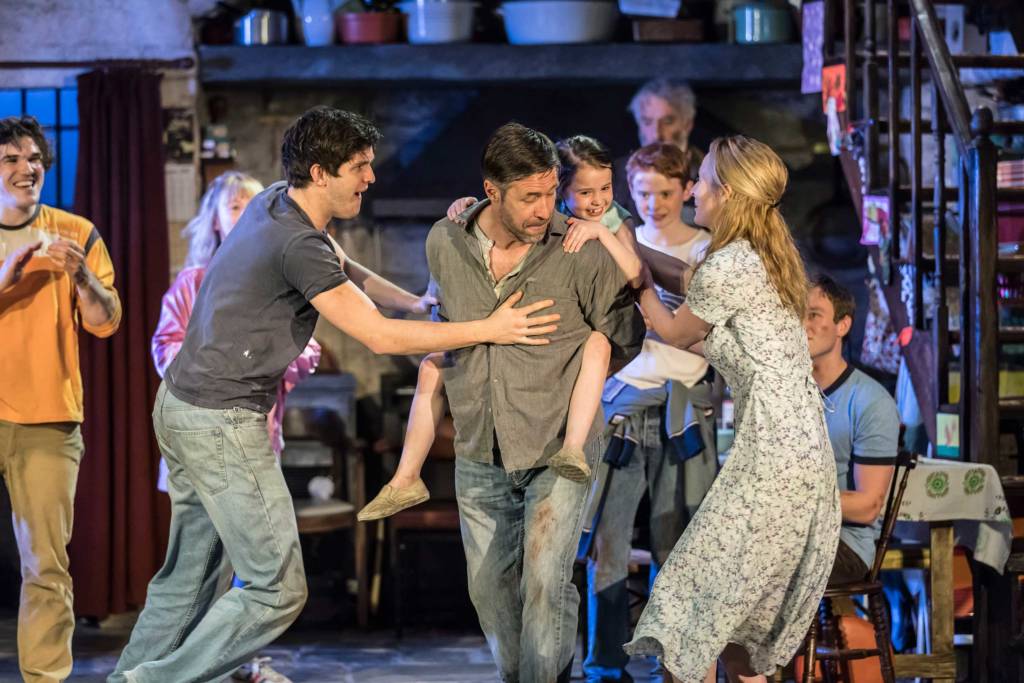

Photo: Johan Persson

Jez Butterworth’s The Ferryman offers a raucous yet tender depiction of family life in 1980s County Armagh. We were waiting in anticipation after the huge success of Jerusalem, as well as the The River, and once again Butterworth’s writing is captivating and rich enough to sustain the intimate view of a family over twenty-four hours in one setting.

Butterworth’s sense of realism is peppered with mythical references, and even the title is a nod to the ferryman of Hades in Greek myth, Charon. This is another aspect of the script which is consistent with his previous work. The movement of time is dealt with carefully and commented upon subtly, with everything building to the climactic harvest meal and its tragic aftermath. Despite there only being one main set, the attention to detail is wonderful. The Carney farmhouse kitchen seems to have been inhabited for a long time by a large family and includes everything from children’s drawings up the stairs to worn out looking furniture.

But really it is the enormous cast, from a live goose to a tiny baby, that makes the play what it is. Despite there being so many characters, each one shines in the moments they are given. The two leads, Quinn Carney and Caitlin Carney, are charismatic, loveable and complex, portraying their sense of longing for one another throughout. They manage to hold onto the audience’s sympathy despite displaying moral ambiguity. True to Butterworth’s characters, it is their flaws that make them what they were. Paddy Considine’s Quinn is the charming, tragic hero, and in a play with so many different characters with their own moments, his unfaltering performance is the glue that holds the piece together. Caitlin’s frank outlook on life and tendency to drink and swear in no way diminishes her unabiding love for her her son and the family she has become part of. It would be easy to resent the character for her magpie tendencies, but it is Laura Donnelly’s performance that make empathising with her easy.

Photo: Johan Persson

One of the most captivating scenes takes place when the adolescent boys of the family sit around drinking in the sleeping house. Another performance that shines out at this point is from the young Michael McCarthy. He delivers his cutting lines with confidence and hilarity. His smooth undermining of his siblings’ bravado slices through the growing tension and increasing silences of the kitchen. One would never have guess that this play is McCarthy’s professional debut.

There are, however, some distracting aspects that might give an audience pause. It often veers towards the sentimental Eastenders ‘We’re family’ cliché. While it makes sense that so much weight is placed on holding the family together, it is repeatedly shown to us on a plate in a way that isn’t wholly necessary. The high consumption of alcohol is also unrealistic to the extent that the two leads would have to be superhuman to manage no sleep and consume so much liqueur. Perhaps it would be more plausible if there were implications of vomiting or hangovers, but that has never really been Butterworth’s style, as it contradicts the idea that everyone is damaged yet made of steel. In this case Irish steel. There has been some criticism that the play is overly indulgent of national stereotypes: the constant drinking, the jigs, the loud family rows, the aunt seeing the banshees at the window, and let us not forget the frequent visits from the head of the IRA.

Photo: Johan Persson

However, it is testament to the excellent cast and direction that, despite this, it always remains a human story about how doubt, love, and fear can tear families apart, and how sometimes it doesn’t quite work no matter how hard a man tries. Quinn Carney tried to be a family man and husband but fell in love with his sister in law. He tried to throw himself into the farm and forget his dark past but it came back to haunt him. He tried to break the cycle only to see his younger relatives fall into the same situations. Watching his fight is both magical and heartbreaking.

Politics, family, love, loyalty: all these things coexist in an aggressive, tumultuous storm in which it is difficult to survive. This becomes blatantly clear in the final act. The play’s moral ambiguity is complex and deeply human in its changeability. It is no Jerusalem, but despite it’s faults, Butterworth has shown the raw beauty of humanity and a simple life.

Filed under: Theatre & Dance

Comments