Frank Walter, source

A turmoil of a life

Francis Archibald Wentworth Walter, self-titled 7th Prince of the West Indies, Lord of Follies and the Ding-a-Ding Nook, artist, sculptor, photographer, composer, writer, and philosopher from Antigua, could have been a mythical personality. He could have been considered a saint or a prophet, serving as a highly respected spiritual leader or teacher, a shaman or a wizard, perhaps, in some other times.

But he was destined to live in the complicated space-time of post-colonial Antigua. A place still heavily charged with the colonial stigma, racialised politics, and white supremacy practices. And Walter was a genius mixed-race kid, a descendant of a white European aristocrat slave owner illegitimately paired with an enslaved woman, an utterly confusing past for his luminous but also ultra-sensitive mind.

Frank Walter’s life, talents and career have a cinematic quality. So peculiar and unique that they seem to belong in fiction. Born in Antigua in 1926, he was such a charismatic child that his tutors –in the very prestigious school he had the opportunity to attend– prompted him to follow law or medical studies. He nevertheless preferred an agricultural career near nature and the land that he loved. In fact, learning from a young age about his ancestors had produced in him a heavy combination of guiltiness with delusions of aristocratic grandeur. Strongly influenced by these complexities he developed the rather daring ambition to become a sugar planter and join the white upper class to which his ancestors belonged.

Frank Walter, source

Bright and talented as he was, he became the first black manager of a major plantation in 1948. However, after a couple of years, he left this post to travel in Europe with his cousin and dear one Eileen Galway. He aspired to pursue new skills and cutting-edge agriculture practices, eager to help his people outgrow their production and get emancipated from the strict colonisation regime. At the same time, he needed to deal with his genealogical restlessness.

Yet, the times were very hard in the West for a young black man of his ambitions. During his travels, Walter confronted violent racism and discrimination. He was rejected by the white members of his family and was obliged to leave and forget Eileen. As he couldn’t find a job appropriate to his studies and skills, he ended up doing menial jobs much below his expectations and even being institutionalised because of hallucinations. Despite racial barriers, scold, internment and the consequent trauma, young Frank persisted in researching and studying for his purposes.

After ten years, he finally returned to his country, fervent to practice all the knowledge he had gathered, and found the sugar industry in decline and only rejections to his proposals. Walter, not giving up, practised farming and experimented with local energy resources in Dominica. When the state confiscated his land, he went back to Antigua, where he became involved in politics while working as a photographer. After he faced disappointment once again by the low acceptance of his political visions, he retired in the isolated house he built by himself on an Antiguan hillside, and dedicated himself entirely to writing and practising his art.

There, and for almost two decades until his death in 2009, Walter found his salvation in art. A marvellous synthesis of his legendary polymathy, his turmoiled past, adventures and disappointments, were expressed and realised through multiple forms of visual, audio and textual “autobiographies” and historical and philosophical essays that reached 25,000 pages.

Frank Walter, source

The Leonardo of the Caribbean

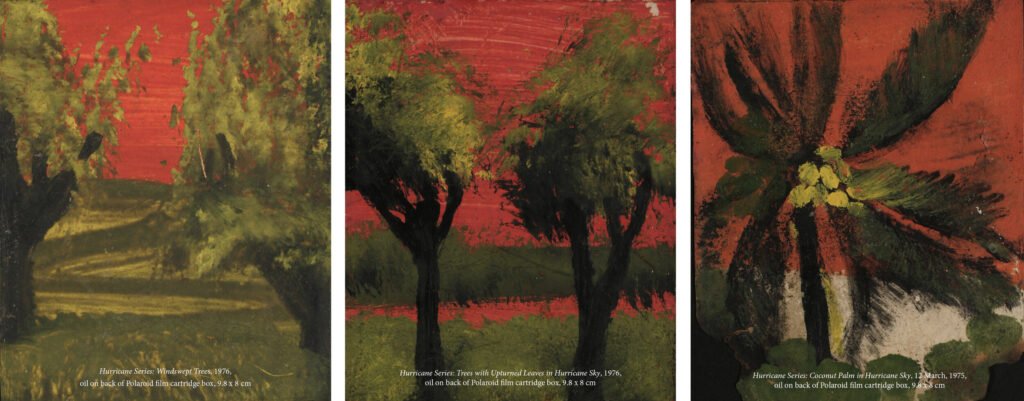

Frank Walter’s painting retains its own distinguished identity although he has adopted many different styles, been experimenting with numerous media, qualities, materials and formats.

I encountered his work for the first time in the David Zwirner gallery a couple of months ago, and I was amazed by the vast diversity of his practice. His painting ranges in subjects and styles from minimalistic or abstract miniature landscapes to meditative works of geometric abstraction, reminiscent of sacred mandalas or flirting with Kandinsky and Hilma Af Klint’s imagery. His multiple sources of inspiration include, among other stuff, Scottish lands and Antiguan nature, famous personalities and his scientific studies.

What struck me the most though, was his personal and poetic approach in all the various media and subjects, his unusual use of colour and some small almost photographic unexpected “glimpses”, psychologically charged and influenced by his career as a photographer: the sudden flight of birds on a mauve-pink sky, a Turnerian wild seascape, a close-up of a watermelon or a tambourine on a colourful background.

Researching his oeuvre more broadly, I discovered and admired an art-brut quality in playing with forms and sizes, his particular and sometimes tragic sense of surrealism in paintings like his self-portrait as Jesus Christ, his gestural freedom as it appears in his coconut woman or his “Dipsomaniac” Hitler and the tenderly childish perspectives in works like “Self-portrait in a tree”.

Apart from the lion and dragon’s heraldic symbols and imagery (that are linked to Walter’s obsession with his royal ancestors) there is another frequent motif in many of his paintings, dominating them and often covering the background-like these forms that block your vision after you’ve looked constantly towards something luminous: the mysterious shape is nothing less than the Antigua’s map.

This Leonardo of the Caribbean Sea had a mind brilliant but fragile. His lyrical and melancholic use of Antigua’s map dictates his drama, a continuous and agonising conflict of grandeur’s illusions and patriotism, an everlasting haunting by his origins that shadowed the whole of his oeuvre.

Walter’s non-medicated schizophrenia – mostly confronted as artistic eccentricity through his life – in combination with the mixed feelings produced by his controversial black-white lineage and the trauma of the systemic racism he encountered immensely in Europe, led him to doubt his very own colour. Even before leaving for his 10-year trip to Europe, he used to call himself “Europoid” and there are works where this belief is evident, like the “Aristocrat-Self-portrait”. As the art historian, curator, and author of his monograph, Barbara Paca states, during the seven-year period in which she interviewed him, Walter believed he was white.

Frank Walter, source

Frank Walter, unveiled

It was eight years after his death that Frank Walter finally received the international recognition he deserved. In 2017, his work represented the Caribbean nation Antigua and Barbuda at the 57th Venice Biennale, in his country’s first participation. The exhibition was curated by Barbara Paca and had the glorious title “Frank Walter: The Last Universal Man, 1926–2009”.

Many exhibitions followed all over the world. Today, Frank Walter’s legacy comes to a thrilling retrieval as he is finally acknowledged as one of the Caribbean’s most important, intriguing, and inspiring artists. His case remains indicative of the persistent invisibility of the colonised people’s genius and creativity, the multiplicity of traumas and identity crises produced by the systemic racism and discrimination in Europe and ex-colonies and shows how art can be a powerful and revolutionary language to manifest all these issues.

Comments