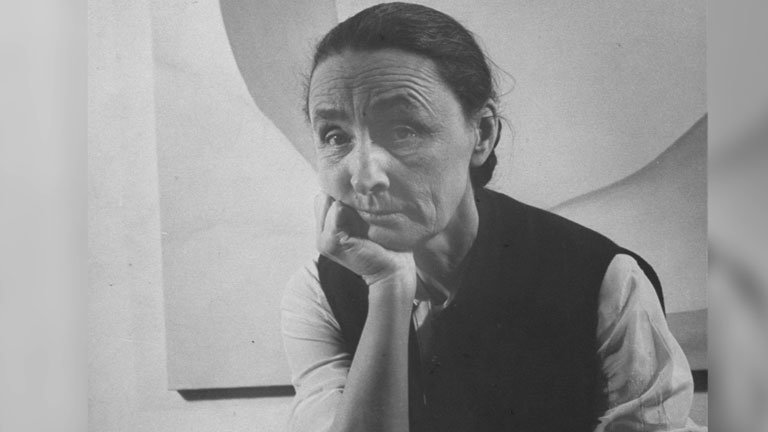

Georgia O’Keeffe: Not A Woman Artist

August 23, 2016

It is true that for many – for most, even – the work of Georgia O’Keeffe instantly brings to mind the image of the artful vagina: yonic ripples and folds, a metaphorical ‘flower’, rather than the literal one she always professed to be her true muse. Beautifully coloured, with sensitivity and fluidity of line, but, inescapably, a vagina.

These sexual connotations and gendered readings have gone hand in hand with the artist’s international recognition, but do the longstanding erotic interpretations of O’Keeffe’s work do the artist a disservice?

White, male artists of the twentieth century enjoy the privilege of numerous, contrasting and multi-layered interpretations of their work. O’Keeffe though, is often treated one-dimensionally, put in a box labelled ‘flower paintings’, her voice is silenced while, ironically, her feminist credentials are lauded. We skim over whole periods of her work because they do not fit our preconceived notions of what an O’Keeffe painting is, but in doing all this, we risk denying her her rightful place in history. She was, after all, a modernist pioneer and complex, multifaceted artist.

Tate Modern’s hotly anticipated O’Keeffe retrospective opened recently, and it certainly appears to be distancing itself from stereotypical readings. It aims to look at her work, which is rarely seen in the UK, with a fresh gaze, and examine not just her famed flower close-ups, but the early charcoal sketches which first caught the attention of gallerist (and later, O’Keeffe’s husband) Alfred Steiglitz, as well as her New Mexico landscapes, and river paintings. The exhibition seems a concerted effort to resituate the flower paintings as part of a diverse and historically significant body of work.

But who is ultimately responsible for creating and perpetuating the pervasive sexualised view of O’Keeffe’s paintings? Her husband and early champion, Alfred Stiglitz,? The art critics? Or maybe even the third wave feminists who adopted her, and her most famous paintings, as celebrations of female sexuality, against the artist’s own assertions.

O’Keeffe began her artistic career at a time when Freud’s theories regarding women and sex were beginning to be discovered, and seen as ground-breaking tools for interpretation. Freud perpetuated the concept of women as sexual beings, but only in the sense that they were the objects of men’s desires, not self-determining individuals with their own needs and impulses, and Stieglitz’s efforts only served to compound such readings.

Alfred Stieglitz was an art promoter and photographer, owner of the New York gallery 291. On seeing O’Keeffe’s work for the first time in 1915, he is said to have exclaimed ‘at last, a woman on paper’, and he struggled to progress beyond that limited view, seeing her as a woman artist whose work was solely concerned with female experience. O’Keeffe pushed against this gender pigeon-holing, but her voice was rarely heard above that of Stieglitz, whose writing often seemed to reduce O’Keeffe, and women in general, to their reproductive qualities: ‘The Woman receives the World through her Womb’, he said, that being ‘the seat of her deepest feeling’, her ‘mind’, he added, ‘comes second’.

In 1921, Stieglitz was making a concerted effort to sculpt a certain image of O’Keeffe. He planned an exhibition of his photographic portraits, many of her, including several nudes. The photographs of O’Keeffe present her as female object, almost creature-like, examined by the male lens of Stieglitz’s camera. It is little wonder, then, that critics of the time were similarly one-track-minded in their views of her work. In 1922, Paul Rosenfeld, a critic for Vanity Fair wrote, ‘There are spots in [O’Keeffe’s] work wherein the artist seems to bring before one the outline of a whole universe, an entire course of life, mysterious cycles of birth and reproduction and death, expressed through the terms of a woman’s body. For, there is no stroke laid by her brush, whatever it is she may paint, that is not curiously, arrestingly female in quality. Essence of very womanhood permeates her pictures.’ Rosenfeld insists that no matter what subject she turns to, O’Keeffe’s femininity cannot help but flow unbound through her work – an uncontrollable force of nature, that Other with which the feminine is so often made synonymous.

Other critics were less flattering, but equally as fixated on O’Keeffe’s gender and the perceived sexuality of her work. In the same year, modernist painter, and 291 artist, Marsden Hartely, published a book in which he described O’Keeffe’s painting as, ‘probably as living and shameless private documents as exist’, adding, ‘by shamelessness I mean unqualified nakedness of statement.’ She was hurt by what she felt was a absolute misinterpretation of her work, but later seemed to become somewhat immune to these underdeveloped critiques, stating ‘I have already settled it for myself so flattery and criticism go down the same drain and I am quite free…Someone else’s vision will never be as good as your own vision of your self.’ And her vision was indeed opposed to that of the male dominated art world, and her husband’s close circle of critic friends.

O’Keeffe strove to be recognised as a brilliant artist, exclaiming famously: ‘I am not a woman painter!’ She lived in a time in which there was an unspoken assumption, an unchallenged belief, in women’s inherent inferiority. To be a ‘good woman artist’ was to be ‘good, for a woman’, and O’Keeffe knew this. She was incredibly astute when it came to analysing the mental working of her male commentators, speaking of Stieglitz’s portraits of her, she said the photographer was, ‘always photographing himself’. Rosenfeld commented on these pictures, too. For him they had a broader symbolism – in them he saw ‘not Stieglitz, but America, New York, ourselves’. How telling that no one seemed to see Georgia at all.

Her flower paintings have been subject to a similar project of co-option. While her contemporary critics required that her work represented the whole of womanhood, viewing it as the epitome of virtuous feminine eroticism, and scarcely addressing the artist at all, her 1970’s reincarnation as feminist icon similarly ignored or fabricated the person behind the art, foisting an unwanted mantel upon the artist.

Third wave feminists celebrated her vulvic flowers as having made women’s sexuality the subject rather than the object in art, active, rather than passive. She was portrayed as a pioneer of ‘female iconography’, but this had never been her aim, and though she was feminist in her views about her own work, in the independent way she lived her life, she baulked at suggestions of explicit sexual content in her art.

In a passage intended for Stieglitz, but that could be justly directed at all these myth-making admirers, she wrote, “I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower, you hung all your associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see – and I don’t”.

It would be somewhat ridiculous to suggest that O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are flowers and nothing more, and of course there is a place for interpretations involving sex and womanhood, but we should never assume that art created by women must inherently be, at root, about women. We would not do that to a male artist. O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are complex experiments in abstracting from nature, self-expressions through line and colour, exercises in selection, elimination and emphasis, getting at ‘the real meaning of things’, and occasionally, perhaps, you might see a vagina.

Comments