‘My images are not necessarily about the woman in the picture. They’re about the character or experience that she represents. They’re icons rather than individual life stories.’

This quotation, emblazoned on the wall of the first major survey of Hannah Starkey’s work at The Hepworth Wakefield, which draws upon perhaps the largest concern of those encountering her work for the first time. Whilst so much of our current discourse about media and art surrounds the question of ‘authenticity’, Starkey situates herself firmly in the blurred, liminal space between fiction and truth. The images, reminiscent of street photography, are a series of carefully crafted visions of femininity. They intend to create a window into ideas far bigger than the individual. A slippery sense of a unified existence refracted through the image of a female body.

‘Wakey Tavern’, Hannah Starkey, 2022.

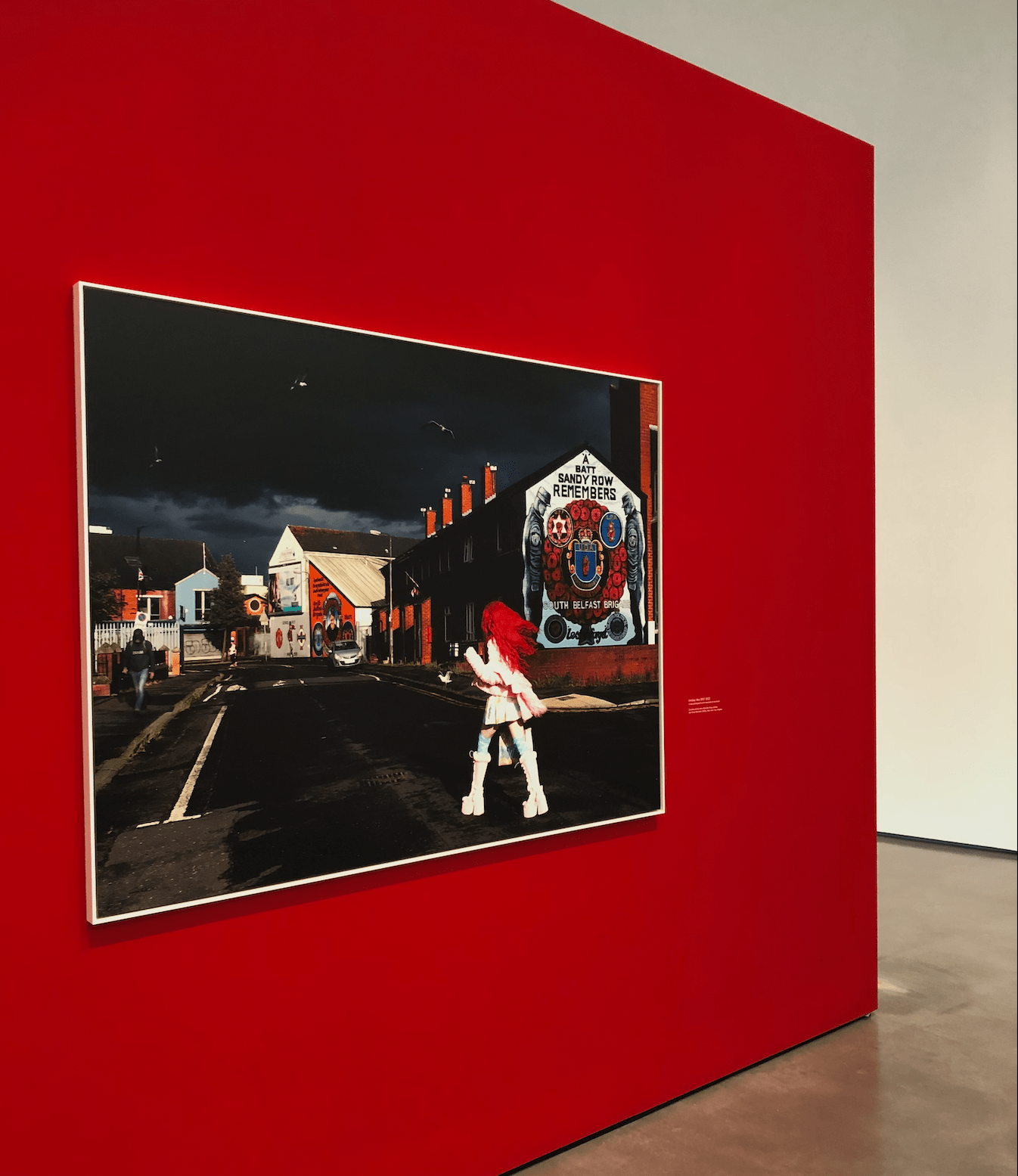

Whilst the corporeal female experience is central to Starkey’s exhibition, it is vitally dictated by interactions between body and space. Both in her work and the rooms of the gallery itself, ‘In Real Life’ delineates the journey of Starkey’s creative practice and, in turn, womanhood over time. Starkey self-identifies as a ‘flâneuse’, a psychogeographical wanderer distinctly reclaimed and redefined from earlier iterations through her femininity. A large portion of her work takes place in cities, seeking to highlight the quiet, often unseen moments of the anonymous woman in the metropolis. The women integrate into their surroundings as much as they operate within them as a foreign object. They ask you to look at the world, how they interact with it and how it responds to their touch, with Starkey’s photography carving out a distinct place for them within it.

‘Untitled’, Hannah Starkey, January, 2013.

United in their quiet, quotidian womanhood, the subjects in the collection often transcend spatiotemporal relationships. Grey hair and pink hair sit in harmony, images of women divided by sea and political alliance are suddenly side by side, not as bold or subversive statements but as an embrace of variety. Starkey’s work does not seek to homogenise, there is an importance placed on difference which is apparent when viewing the breadth of her collection. Images of women running across demolished buildings in Ireland placed in the same vicinity as an elderly lady celebrating a football result, roaring faces at protests appear next to vacant gazes through cafe windows. No representation is demonised nor celebrated more than another, they are simply existing simultaneously, in complete concordance.

Starkey shoots many of her subjects from behind, or with their focus seemingly elsewhere, perhaps representing the moments in which the facade drops, exposing the reality of womanhood when it seems like nobody is watching. This is what makes her creative practice so interesting, an ironically constructed image that seeks to counteract a neurotic cultural obsession with self-curation. Through this, we begin to see each room profess a complicated relationship between intimacy and inaccessibility. We are all too aware that, as close to these subjects as we may feel, we will never truly know the women outside of the frame. We are granted space to project onto these women, relate our own experiences to their absent stares, but they are not ours to take. We are forever taking the shape of the potential voyeuristic onlooker that Starkey seeks to exclude.

‘Untitled’, Hannah Starkey, May 2022. Photographed at the ‘In Real Life’ exhibition at The Hepworth Wakefield, 2022.

This uncomfortable sensation is in line with Starkey’s ethical method in itself. Whilst staged, she goes over the image with each of her subjects in depth in order to democratise the form. Though the knowledge of this staging at first breeds disappointment, it is exactly this that provides her subjects with autonomy. The real reasons behind the fleeting movements and interactions that first sparked Hannah’s interest remains theirs and theirs only. The images themselves become not so much a work of fiction, but perhaps autofiction or memoir, as Starkey and her subjects reflect on and attempt to represent an organic mode of living.

In one room, a large portion of her more recent work is placed together in a series of images referencing the beauty industry’s influence on young women. In her earlier work, Starkey’s subjects appear unaware that they are being watched, yet in her later work are all too aware of a voyeur. The camera’s presence, however, remains unobtrusive. These more recent images tackle the issue of performance head-on by seeking to include the slippery gaze of the media. Her own medium is called into question, as references to phones, cameras and mirrors beyond Starkey’s lens transforms each young woman into a self-conscious performer. It seems that there is an increasing awareness of the near impossibility of an authentic, relaxed self that Starkey sought to represent in her earlier career.

‘Untitled’, Hannah Starkey, October 1998. Photographed at the ‘In Real Life’ exhibition at The Hepworth Wakefield, 2022.

In Real Life provides Hannah Starkey’s vast body of work with the space to be viewed as a complete project. It becomes a cataloguing of quotidian western womanhood in its various shapes and forms, an ongoing survey as opposed to an exhaustive list. In turning toward the smaller, silent moments, Starkey’s photography raises interesting questions regarding the ethics of proximity. As authenticity is called into question, these images remain loaded with enough emotional depth and uncanny relatability to shake any woman down to her core.

***

‘In Real Life’ is on at The Hepworth Wakefield until the 30th April 2023. Click here to get your tickets to see this wonderful exhibition.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: art, artist, body, Diversity, exhibition, female, femininity, figure, Form, gallery, Hannah, liminal, photography, society, space, Starkey, The Hepworth Wakefield, Unity, women

Comments