In the beginning: The Bristol School of Artists

October 17, 2015

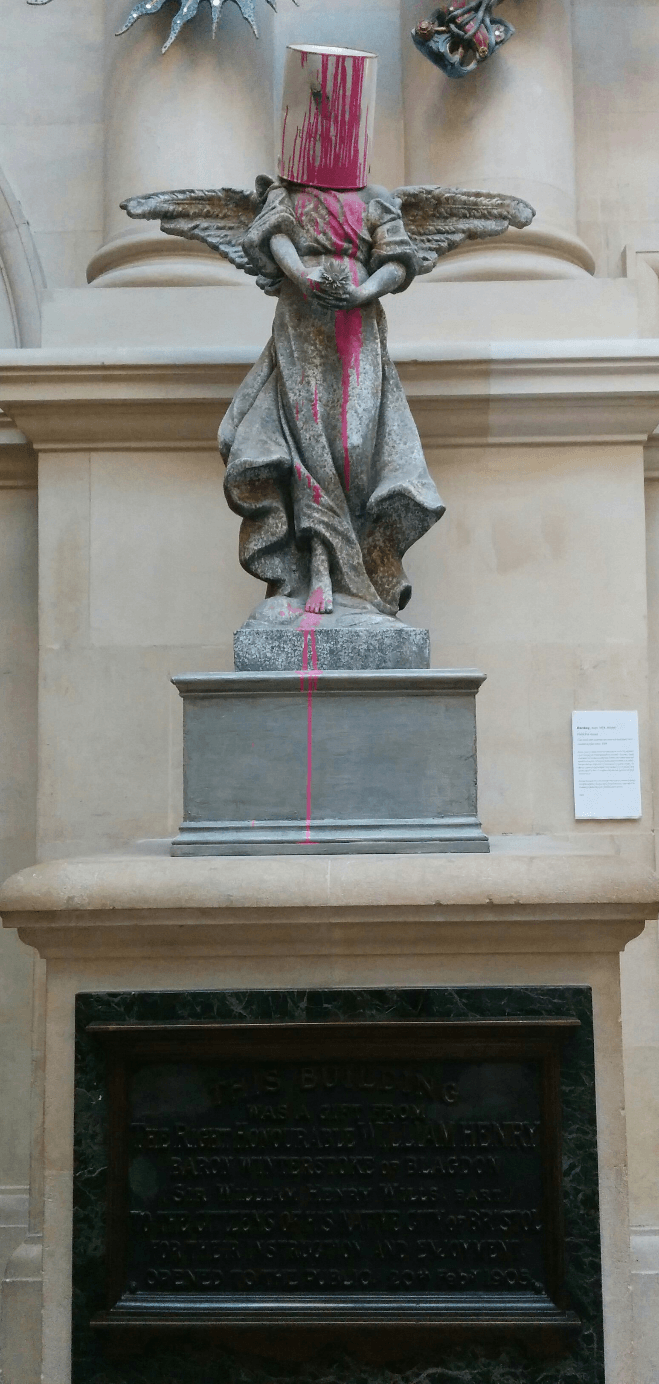

Photo Credit: Hannah Emadian

Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, like most city museums, plays host to a variety of permanent and travelling exhibitions ranging in origin. Whilst relatively small, the building stands grandly on Queens Road, with a high arched ribcage of a ceiling and labyrinthine intestinal staircases, which lead you on your voyage of discovery.

The B-MAG (as it shall forevermore be known) seamlessly integrates the modern (necessities such as an information desk, digital information points, museum shop, café, and ground floor loos) with historical architecture. The first piece of art to capture my attention seems to address the same relationship between classical and contemporary, but with far less subtlety: before me stands a Banksy, a female statue, with an upturned can dripping shocking pink paint down her anonymous torso. Whilst pleasantly amusing and thought-provoking as I always find Banksy to be, today I am here to learn about the genesis of the Bristol art-scene. I am here to get acquainted with the Bristol School of Artists.

On the top floor of the museum, I am transported to ‘between roughly 1810 to 1840’, as the exhibit label informs me, when a group of artists and their friends, began documenting the city that they lived in. Collectively, Edward Bird, Francis Danby, James Johnson, William James Mueller, William West, and company, became retrospectively known as the Bristol School of Artists, despite being neither affiliated with a school, nor actually from Bristol.

Whilst the exhibit did not depict the gang as particularly glamorous or alluring – their regular meet-ups were described as civilised affairs during which they really did just sketch and paint together – the result is reflective of their hard work and attention to detail. The gallery walls are lined with decadently framed oil paintings informally separated into two distinct categories.

As expected, the majority of the space is occupied by scenes of early nineteenth century Bristol, but these scenes are interrupted by fantastical landscapes and apocalyptic biblical depictions. Introduced as the leader of this movement, Francis Danby is believed to have encouraged the group to paint poetically, and romantically. Looking at various perspectives of the view from Leigh Woods, across the Avon Gorge, I certainly feel that they have achieved their intended atmosphere. It is easy to imagine that Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, or Blake are amongst the figures seated on the grass, if you exchange the artist’s easel, for the poet’s pen. Interestingly, the Bristol School of Artists are not commonly associated with the Romantic movement of art, literature, and intellectual thinking, but, I saw many parallels.

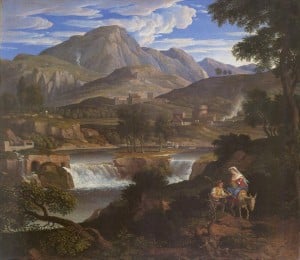

Photo Credit: Hannah Emadian

The compositional and thematic similarities between the first painting, and the latter two suggests the Bristol School of Artists’ success in achieving the romanticism that Danby encouraged. All three paintings feature cloudy blue skies, rural waterscapes surrounded by green, with figures positioned towards the bottom right corner of the scene, with bright fabrics in red, white and blue.

Photo Credit: Hannah Emadian

Photo Credit: Hannah Emadian

More than the aesthetic similarities, however, it is the atmospheric likeness that struck me. Many of the nature scenes that I saw at the B-MAG evoked a sense of tranquillity. If people were included, they were secondary to the scenery, being relatively small and often painted from behind, which suggests that even the figures within the scenes were captivated by the natural beauty before them.

At a lecture held in the Wills Memorial Building, just next door to the museum, I recently learnt that the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge held a series of lectures in Bristol on Green politics at around the time that these artists were working and living here. Coleridge’s opinions and ideas were startlingly contemporary – the fact that the same conversations are still being had today demonstrates the lack of progress we have made in the right direction.

The point of this digression is to elucidate the fact that discussions of nature and romantic ideologies were in vogue in the city at the time. As the current Green capital of Europe, it is fair to say that the conservation of the natural environment and its beauty are still at the fore of the Bristolian mind set. With that in mind, I feel that this series of paintings is essential viewing for art-lovers and Bristol fans alike, if only to see where a city, famous for its guerrilla graffiti artists and emerging new talent, began on its artistic journey.

For more information on what’s on the second floor, home to art, at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, visit: http://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/bristol-museum-and-art-gallery/whats-at/second-floor/

Follow Hannah Emadian on aseparateworld.tumblr.com

Comments