Interview with Turner Prize nominee, Ingrid Pollard

November 24, 2022

Ingrid Pollard @ Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Liverpool. Image credit: Joanie Magill

From a professional perspective, Ingrid Pollard is pleased that her Turner Prize nomination means photography is being recognised in an awards landscape that often ignores it. Personally, this nomination “is recognition for resilience and continuing to make work.”

The Turner Prize ‘is awarded to a ‘British artist for an outstanding exhibition or other presentation of their work in the preceding year as determined by a jury’. One of the four nominees, Ingrid Pollard is being acknowledged for her solo exhibition Carbon Slowly Turning at MK Gallery, Milton Keynes.

An important figure in the Black British art movement in the 1980s and a feminist and LGBTQ activist, Pollard’s practice interrogates Britishness, race, sexuality and identity chiefly through the materiality of photography, but also film and sculpture.

Carbon Slowly Turning was a major survey of the artist’s substantial body of work over her 40 year career, featuring hand-tinted landscape photographs, an installation of ceramic boats, kinetic sculptures, a film and four large scale abstract photographic images. I asked Pollard how she approached distilling four decades of work into the installations in the two rooms of her Turner Prize exhibition. She explains, “It was work from Margate and from MK (Gallery), how the pieces worked with the audience and what work works together, works that could sit in a room together but had a relationship with each other and were impactful”.

Ingrid Pollard @ Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Liverpool. Image credit: Joanie Magill

Seventeen of Sixty Eight (2019), in the first room, is a body of work rooted in research spanning over two decades. It is an exploration of people of African descent in British life in a series of photographs, artefacts, extracts and redacted extracts from literature, and a set of colourless embossed prints on white paper. Pollard visited all of the sites that bear the tangible and intangible presence of the ‘Black Boy’ whose presence permeates England’s towns and countryside, showing how black people have been part of England’s history for centuries. Pollard has been “collecting for nearly thirty years – going to the places, the public houses and doing research around them on Englishness and leisure and society and landscape.”

The landscape photographs make me think of Willie Doherty’s work. Doherty’s documentation of seemingly neutral landscapes and spaces are inscribed with the legacy of trauma and violent history. In Seventeen of Sixty Eight, Pollard presents an inventory of the legacy of colonialism and slavery. She challenges the official voice, interrogates the concept of Britishness and race, disproving an objective historical truth that renders black people invisible while at the same time being on public view. “There are all these traces and elements, incidents that might have taken place. There’s also the disappearance of them and ways in which you refer to people of African descent.”

Ingrid Pollard @ Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Liverpool. Image credit: Joanie Magill

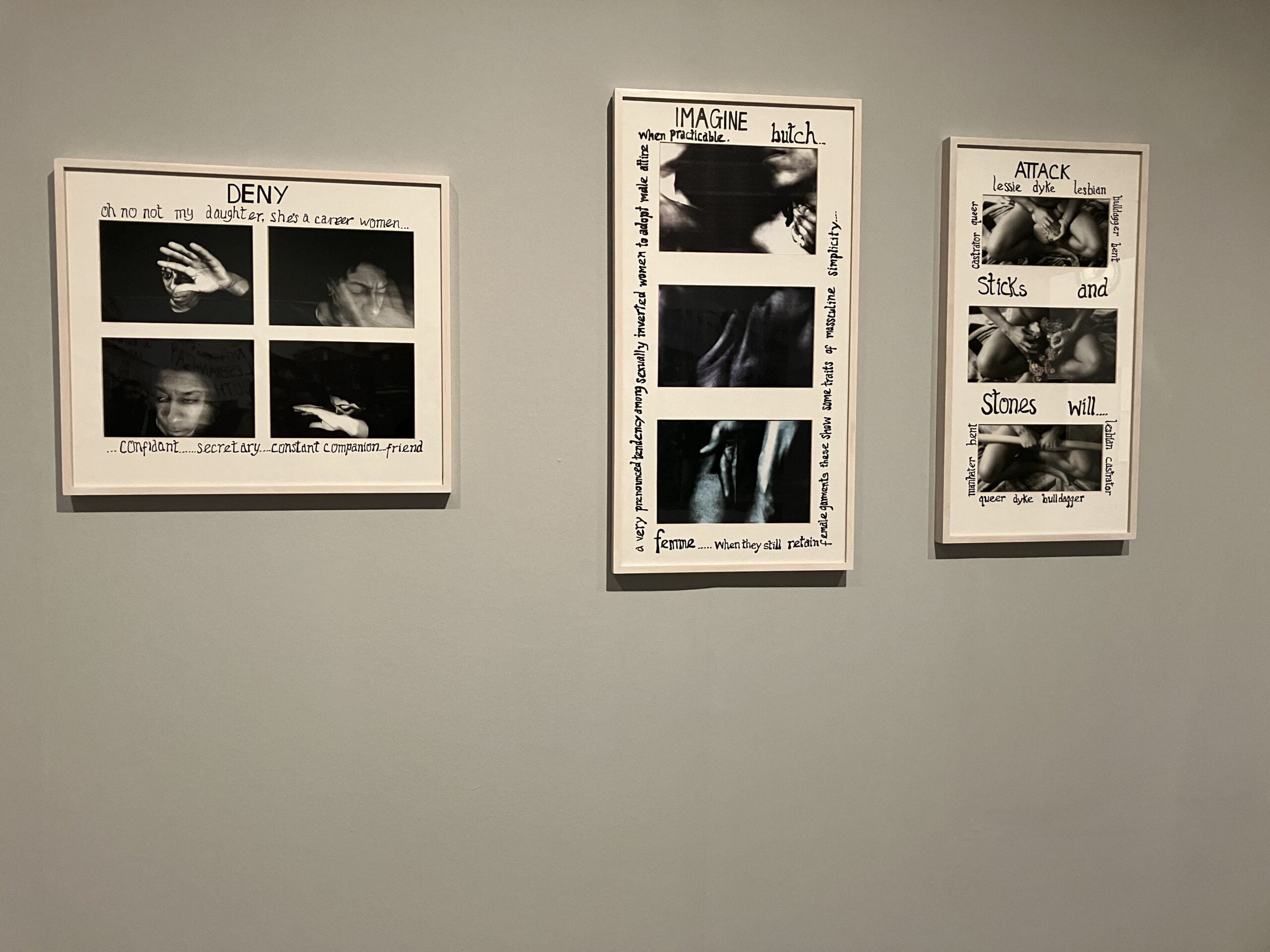

In the second room, a mix of early and recent works examine the dynamics of power in relation to the body. In the previous room, the body is invisible; here it is in distress. Whether from police abuse, or from the medical establishment, Pollard’s work in this room explores “the repetition of state control and how people work against that.”

The photo series DENY:IMAGINE:ATTACK (1991) and SILENCE (2019) feature fragmented images of the body, around the edges of which are handwritten homophobic assertions. Pollard explains how she was looking at parts of the body on a grid system and referring to the medical text of Havelock Ellis. “He’s looking at so-called ‘inverts’. It’s the state language of psychology that is repeated whatever way you want to talk about this. Photography has always been implicated in medicine.”

Ingrid Pollard @ Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Liverpool. Image credit: Joanie Magill

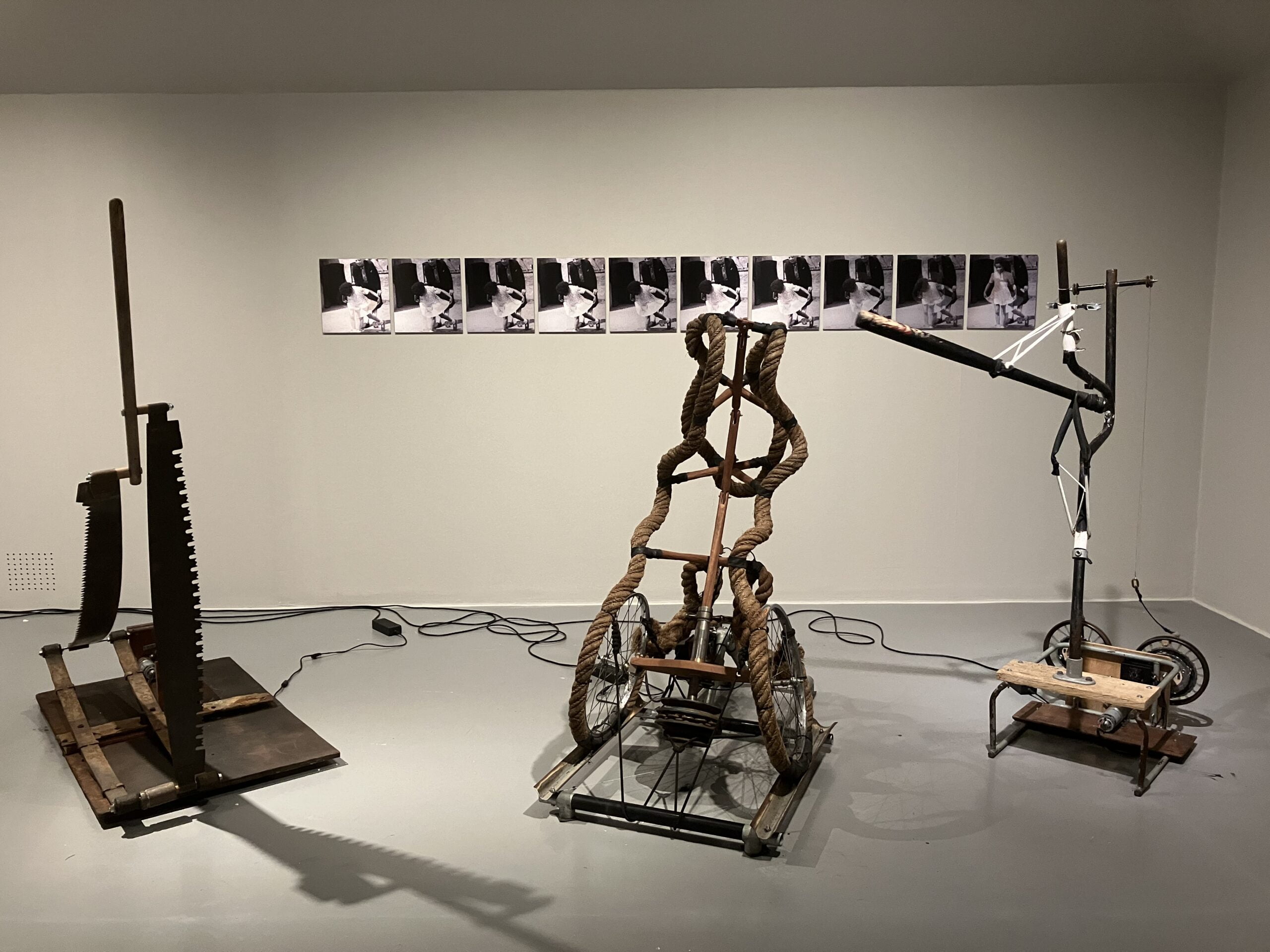

Repetition and abuse is reinforced in Bow Down and Very Low–123 (2021), a series of lenticular photographs taken from footage of a 1944 propaganda film featuring a young black child making an awkward bow. Pollard says, “The lenticular images, as you move across them, she’s bowing to you in a particular sort of way.” In front of the photographs are three kinetic sculptures made using found materials in collaboration with kinetic artist Oliver Smart. The sculptures are both mesmerising and menacing – rusty wide-toothed saws, thick ropes, a baseball bat embedded with glass make up the components. The sculptures are almost human in size and their repetitive, jerky movements and materials suggest submission under threat of violence. High up on a nearby wall is a quote by Maya Angelou: ‘now you understand just why my head is not bowed’.

Achieving a long-standing career as a Black female artist takes resilience in an art world that for a very long time kept its door shut. Pollard has sustained herself through the diversity of her practice, friends and activism, “I don’t want to stick to one particular avenue. And I think I just maintain contacts. All those friends, they’ve sustained me really. We go in and out of each other’s lives but I want to maintain that contact cause otherwise I wouldn’t really survive. Politics, art practice, socialising and activism all feel the same to me.” Now, with a Turner Prize nomination, Pollard is receiving “recognition after a long time” that will take her work to a wider audience and open up even more opportunities.

***

You can stay up to date with MK Gallery here, and see what Ingrid Pollard is up to via her site.

Carbon Slowly Turning will be displayed at Tate Liverpool until March 2023.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: art, black British experience, exhibition, feminism, Identity, Ingrid Pollard, material, photography, race, sculpture, Tate Liverpool, Turner Prize

Comments