Inside Out @ Manchester’s Castlefield Gallery

March 27, 2016

Darren Adcock

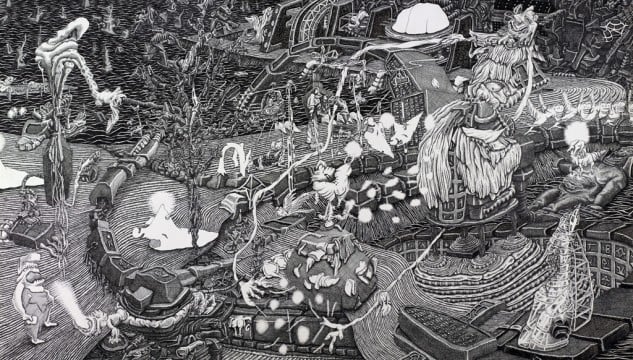

Pig Dogs Missed

The ‘Inside Out’ exhibition at Castlefield Gallery, Manchester, playfully shares its name with a recent Disney Pixar animation, which is an interpretation of how the human mind is governed by its personified emotions. Perhaps in likeness, the artwork chosen for this exhibition has a particular neurotic style. But here I’m jumping the gun.

The reason for the title is the use of work identified as ‘Outsider’ art, a term describing artists who work ‘outside’ the establishment and originates from the french term coined by artist Jean Dubuffet, ‘art brut’ or ‘raw art’.

Co-curated by Castlefield Gallery and artist, writer, university lecturer and art therapist David Maclagan, the artists chosen come from all over the world, although most are working in the UK now. More information about the individual artists can be found on the gallery’s website. It must be acknowledged that a number of these artists suffer from some form of mental health issue or learning disability which to a certain extent influences their work. For example Jenna Kayleigh Wilkinson’s works are named ‘Obsession’, and are numbered. These aptly obsessive, compulsive ‘meta-doodles’ she relates directly to her Asperger’s Syndrome.

Wilkinson’s style can be compared to the incredibly detailed line drawings by Nick Blinko and Richard Nie’s work, but her large scale and minutely detailed abstract drawings are particularly similar in style to the work of Carlo Keshishian and Mehrdad Rashidi. Keshishian’s work in the exhibition is equally as compulsive as Wilkinson’s, taking years to complete due to the minuscule detail required and created on such a vast surface, over several metre wide canvases. Another of his works is far smaller in scale but even more intricate, what appears at first to be abstract doodles, in fact is a diary entry, the words have been created using an outline of black ink. The gallery provides magnifying glasses for these works, and it is amazing how much more can be gained from seeing the intricacy and effort made by the artists to create these seamless masses of undulating lines.

Rashidi’s works are displayed together from floor to ceiling, varied in size, perhaps owing to the wide range of surfaces he draws on (notebooks, envelopes, receipts etc), with faces drawn onto undulating shapes and doodles. After fleeing Iran and settling in Germany, Rashidi began to draw, finding that it relaxed and contented him. Although Rashidi’s works are figurative, the line used to create these shapes is built up, crossing over and over to make a mass, in a similar way used by Wilkinson and Keshishian to create abstract masses. Rashidi’s drawings are filled with nostalgia for his childhood and homeland, and so he has related his practise to a way of dealing with homesickness, therefore using drawing in a therapeutic way .

In the exhibition the work of these two artists is displayed alongside Darren Brian Adcock’s series of drawings ‘Giant Babies’, who, as described on the website, also finds the process of drawing therapeutic. Adcock’s work takes up a corner of the upper floor, creating a small niche for itself which I think enhances the miniature aspect of the collection of wooden frames, drawings and UV lights. A first look at these drawings shows only – time for a terrible cliche – the tip of the iceberg. A small detailed drawing is much more than it seems when lit up, at the push of a button, with UV light. Adcock draws even more intricate fantasy landscapes with invisible ink. It reminds me, quite simply of the human condition that only a limited amount of our individual thought process ever seems to get put across at any one time. Each thought has an underlying series of thoughts and processes that are subconsciously or consciously filtered out of the main point. I think this idea resonates within the whole exhibition, in that the detail and intricacies of the artworks can be directly related to in some cases, and are perhaps representative of the individual artists’ thought processes, whether memory, dreams, anxieties or alternatively a way of meditating and escaping the hubbub of the brain by focusing on one repetitive task.

David Maclagan’s role as co-curator and his experience as an art-therapist could perhaps be said to parallel each other in this exhibition when considering the artists’ experiences. His own work is here displayed over light boxes, revealing the exceptional layering of colours in a turmoil of lines and squiggles. He uses various implements to create these marks including brushes and palette knives. Starting by making a frame, Maclagan describes the resulting works on his website as ‘an inchoate but strangely coherent ‘field’, in which subliminal forms are embedded, as if they were about to emerge from, or to return to, something I call ‘The Ground of All Being’’, which is the title of his series. From these final visual products we can perhaps draw comparisons to Peter Darach’s and Mit Senoj’s colourful, fluid and figurative works also in the exhibition.

I think this idea of ‘subliminal forms’ also touches on some of the fantasy aspects in the work of Marlene Steyn, Andrea Joyce Heimer, and Joel Lorand. Steyn’s ‘Mooney Downside’ covers the back wall of the lower gallery that, using someone else’s comparison, shows a particular Boschian chaos whilst maintaining repetition in certain motifs. Heimer’s works could perhaps be described as calmer in comparison to Steyn’s, in ‘The Rebuild of My Grandmother’s Cabin’, for example, although here the planes overlap and are heavy with detail, including the muscular, silhouetted, uncanny, ‘builder’ figures. Heimer suffers from clinical depression, like a number of these artists, and draws much inspiration from her childhood in Montana (which could perhaps relate to the nostalgia in Rashidi’s work), her works reflecting memories or ‘mythology’.

I could go on probably, in a much more academic and tragic way about the artworks in this exhibition but I think at this point it would be worth recommending the readers to simply go and visit, because I have to say this is a very exciting collection of works. Though this is just one viewer’s opinion, it’s worth going to make your own. There is so much to see and take in, without being overwhelmed, and so much scope for the viewer’s own reaction because of the endless links that can be made between the artists’ work. This could be through connecting with the various mental health issues the artists have suffered; engaging with the highly detailed, linear aspects of the works, say through a magnifying glass or UV light; or finding out more about the world of ‘Outsider’ art. In fact, just to turn this article about ‘Inside Out’ on its head, check out this website for some more information on outsider art: www.outsidein.org.uk, ‘Outside In’ is a registered charity providing a platform for artists who may face obstacles in being accepted into the fine art community, such as health, disability, finance and isolation.

Comments