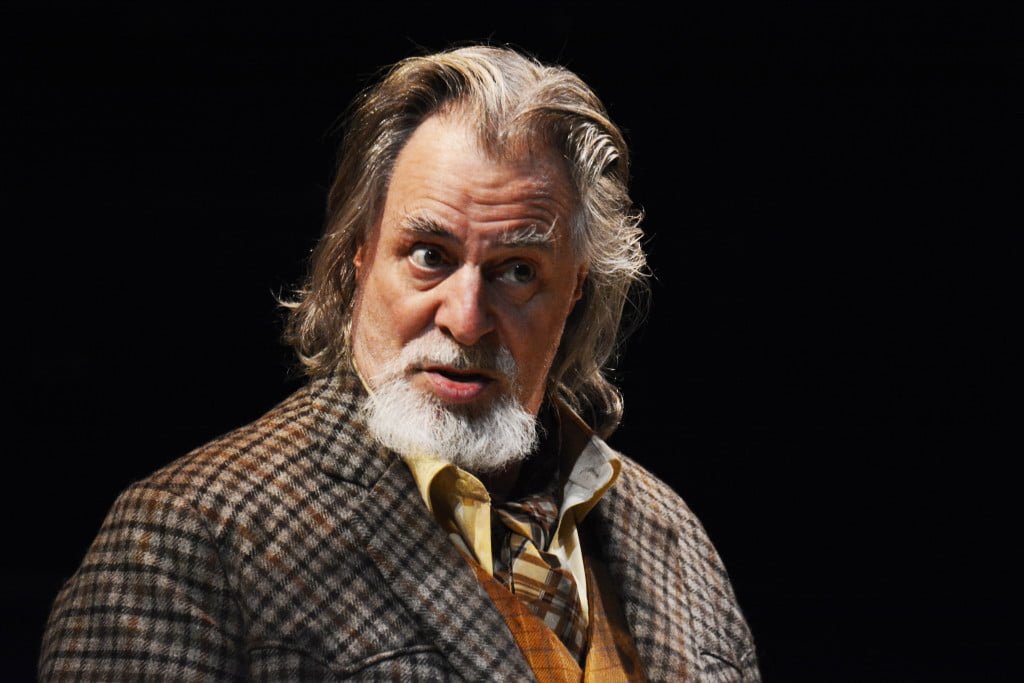

Barrie Rutter as Falstaff Photo: ©NOBBY CLARK

TSOTA’s Rich Jevons talks to Northern Broadsides’ Artistic Director Barrie Rutter OBE about the touring production of Shakespeare’s Merry Wives.

How did you get on with being awarded your OBE?

I took my three daughters, ironic having just played Lear, I thought that was rather nice because you get four tickets. I had a laugh with Princess Anne who was the medal-giver that day. She said: ‘Do they all sound like you in the play?’ I said: ‘Yes, that’s why it’s called Northern Broadsides!’ We had a fun day.

How do you go about directing and playing the lead in the same production?

It’s not difficult, I promise you. Don’t believe those that tell you it’s so hard, that’s bullshit. Sometimes I myself am slightly under-rehearsed but then I catch up very quickly once I’m not looking at other people and how the production can be better. I’ll know first before anybody else when it’s a problem.

Could you tell us a bit about the play, I’d read that Elizabeth I may have asked Shakespeare to write a romance for him?

There’s no evidence of that, it’s just an idea. Journalists who don’t like the play usually use that to denigrate the play. It doesn’t get much done outside of the RSC or The Globe simply because it’s called The Merry Wives of Windsor and you don’t want to put that on in Manchester. So that’s why we’ve dropped all that and we’ve changed the geography and we just call it The Merry Wives.

It’s a fun play. It’s got hangovers from the Henry IV plays because it’s got Falstaff in it and Nim, Pistol and Bardolph and there are references to that. But the references are very tenuous – it’s not the Falstaff of the Henry IV’s, it’s not the white-bearded Satan who sticks men up in front of a cannon and gets money for doing that.

The Falstaff of the Henry IV’s would never go back three times to the same women thinking he can woo them into falling in love with him and get their money. He is scheming and he goes back a second and a third time because he’s all fame and no income. And he gets his comeuppance but Shakespeare is not content with that because the other couples get their comeuppance too. So his target is not just Falstaff.

©NOBBY CLARK

Hasn’t the plotline of the surprised wife and cuckolded husband been done quite a lot before?

It’s been done thousands of times, like in Cervantes and hundreds of Italian plays. These are legendary stories and go back to the Roman plays as well.

Do you think it would be a bit of a break for Shakespeare to write a farce after so many tragedies?

I really do think you’re putting too much intellect on what was a financial situation. He didn’t write the plays [for his own reasons], he was paid to write, it was pure finance. And when he delivered a play there was one payment, the playwrights never got any more money for them. So if Philp Henslow who owned the Rose theatre and the Admiral’s Men or the Chamberlain’s Mem – whoever he was writing for at the time – it was all based on money. Whatever we think about the intellect and psychology of the time – just go back to ‘follow the money’.

And is it a relief for you after King Lear and A Winter’s Tale?

It’s certainly not a breeze – it’s good honest graft. It’s what you do, it’s our job. I’m not complaining, it’s great fun. Laughter is wonderful but it’s also so ephemeral and so elusive. There are some things people laugh at and I think I don’t see what’s funny about this. Or the next night you expect it and it doesn’t come! That’s why you have to wipe every other performance for the experience of it.

How do you approach the farce?

Shakespeare does write it [for farce]. He designs it for you in a way. You’ve got to get into a laundry basket, you’ve got to go behind an arras, you’ve got to climb a tree. With the wit of the production, what are those things? It’s up to the director and the designer and we’ve got a surprise in for you this afternoon!

©NOBBY CLARK

Will there be music too?

The music and dance is part of our DNA and that similar DNA is on show this afternoon. There is less of it [than normal] because the show doesn’t afford as much of it. We have a basic 1920s setting so there is a bit of recorded music at the beginning because there is a party going on off stage. Then that recapitulates at the part of the play with songs and music. Everybody plays or sings or takes part.

What made you set it in the 1920s?

I said to designer Lis Evans that I don’t want it traditional because I’ve seen this play a couple of times in so-called traditional costume and with the style of the dresses the women look as fat as Falstaff! So I wanted it modern also because it’s easier for us to look after on a fourteen-week tour. But I don’t want it mobile phone land, otherwise you’re lost. The 20s was also a period of great fads and the setting is a middle class country sports club which gives us our weaponry as well. We use sporting equipment rather than swords and all that nonsense.

What is the main plot?

There is the plot of a forced marriage which is how Shakespeare ends the play because they marry for love. Therefore their parents get their comeuppance. Falstaff is skint and thinks he can woo the women. Then the other side of the young lass who marries for love is a whole market place about her: A Frenchman who has got more pull at court, so the mother wants him; the young squire who is very rich, and the father wants him. But she marries for love. Those two plots go hand in hand.

What would you like your audience to take away with them, comedy can be so cathartic?

Pleasure is a great educator. And it’s the comedies in which the heart-strings are tugged. We go into a tragedy differently, with expectations of tragedy to happen. But in comedies there is the great power to build you up and let you down. So we’ll do our best!

See http://www.northern-broadsides.co.uk/ for more info about the production.

Filed under: Theatre & Dance

Tagged with: Barrie Rutter, Lis Evans, Merry Wives, Northern Broadsides, Rich Jevons, Shakespeare

Comments