Interview: Helen Mort – Poet & Cultural Fellow at Leeds University

July 28, 2015

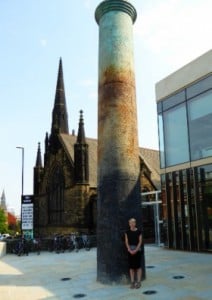

[Photo: Andrew Crowley]

Helen Mort is currently half way through her two year term as Douglas Caster Cultural Fellow at Leeds University. Originally from Sheffield and still based in the Peak District, her potential as a poet was spotted when she won a Foyle Young Poets award as a teenager.

Following a double first in Social and Political Science at Cambridge, her debut collection, Division Street, delivered on that potential, being shortlisted for the Costa and T.S.Eliot Prizes and winning the Fenton Aldeburgh Prize.

Helen Mort

Helen is also a fell runner, a climber, and has recently completed a PhD on neuroscience and metaphor. Somewhat breathless, TSOTA caught up with her, to see how she was taking to Leeds and to her role in the university and the city.

TSOTA: What is a Cultural Fellow?

HM: The Fellowship I hold has been endowed by an alumnus of the university called Douglas Caster, and I’ve been given two years to work with colleagues in the School of English and other faculties, to do a bit of teaching, work on my own projects and make links between the university and other writers in Leeds.

I’ve enjoyed doing a website called Leads to Leeds, which pairs up writers with a Leeds connection. People have been writing poems in response to one another. We’ve had some great collaborations, and I’m hoping to do some events next year and perhaps publish some of the collaborations in print, as well as online.

School of English

TSOTA: What’s your impression of the literary scene in Leeds?

HM: I get the impression it’s in pretty good health and people feel a really strong affiliation to Leeds. What struck me doing the project was so many people wanted to write about the place. There’s quite a bit going on. It may be fragmented, but there’s more than I’ve had chance to attend. I would like to get to Blank Page Industries, the writing space they create on Tuesdays.

I’m doing Word Club at the Chemic Tavern in November with Kim Moore. There are a lot of reading opportunities. Perhaps there aren’t as many open mic events as in some cities, but maybe the problem is joining it up.

I’m always keen to meet new writers and writing groups. I’d love to work with Leeds Young Authors. I admire and respect what they do. I thought We Are Poets was a great film. I would love to do an event with Peepal Tree Press, who are based here. They publish some great writers.

TSOTA: What other projects have you been up to here?

HM: I’ve been working with a flamenco guitarist, Sam Moore, putting on a show I’d like to expand into a national tour. We started with flamenco rhythms, and were surprised how well those matched up with poetry, but we’ve expanded it so we’ve got blues and an Irish jig.

I’ve been working on a novel and a collection of poems. I’ve been doing workshops, open to everybody, sharing work in progress and getting people to write in response.

TSOTA: What will the new poetry collection be like?

HM: It’s mostly to do with women and mountaineering. Some of it’s based on my own experience as a climber and some on the history of women’s mountaineering.

In 2013, I was invited on a trip round the Swiss Alps, following the footsteps of Victorian explorer Jemima Morrell. She went on one of the first Thomas Cook trips round the Alps, and walked phenomenal distances wearing crinoline. She also kept this amazing journal – Miss Jemima’s Swiss Journal. I dressed in crinoline for some of the trip and did some walking and I kept my own journal, but being the 21st century, mine was a blog.

I noticed the poems I was writing about women and climbing linked to some of my other work to do with the body and ideals of beauty, so it meshed together. That’s going to be published next June.

TSOTA: Climbing and running are fascinations for you. Are they easier to incorporate for a poet than for a novelist?

HM: I don’t just find it helpful with poetry, I find it with prose as well. If I’m stuck, I need to get outside and get up high, and then everything falls into place.

Many sections of the novel I’m working on started when I was thinking about what needed to happen and I’d go for a walk and the lines would come to me. It doesn’t have to be inspiring, romantic settings. Since I’ve been in Leeds, I’ve had my best ideas in the walk from Leeds Station to the School of English.

TSOTA: Do any other fascinations figure in your work?

HM: I’m interested in borders, where one thing becomes another. I remember Ian McMillan doing a Radio documentary about what he calls an ‘isogloss’, a place where people stop pronouncing a thing one way and start saying it another. He was looking for one of these lines between North Derbyshire and Sheffield, where I come from. Because I grew up in Chesterfield, 10 minutes from Sheffield, I’ve always been interested in those places.

That’s why I enjoy my journey between Sheffield and Leeds. Leeds has come up very quickly. There’s a lot of newness about the centre. I think it would be interesting to compare skylines of different cities. Sheffield strikes me as having a blunter skyline. Leeds is pointier. I’ve been working with the public art project here, raising awareness of artworks on campus. My most recent one was to respond to a piece commissioned to go outside the new library, called A Spire. It’s to do with upwardness and aspiration, so I suppose that started me thinking about the Leeds skyline.

This spire goes where we’d travel if we could:

new sapling in a concrete wood, not tallest

but most aspirant, height’s newest conspirant.

We court it as we learn. Forever giving looks it can’t return.

TSOTA: From certain facts about you and Division Street, someone might expect something very political, but it’s more nuanced. Is there a post-modern attitude to the political situation referenced in the book?

HM: A lot of people have said they don’t like the cover of Division Street because it gives a misleading impression of the book. It is very stark and oppositional. I just love that image and that’s why I was drawn to it. I didn’t really think about how that would define it. But I thought readers will find their own path and see beyond the cover.

With the poem Scab, a post-modern reconstruction was what enabled me to write it in the first place. I wanted to write about the miners’ strike, because growing up where I did, I got this sense of the landscape and the community being shaped by it: this anti-Thatcher feeling you’re aware of even at that age, and slowly started to make sense of as you got older and saw what a devastating impact the strike had.

I was hesitant because, having been born in ’85, not having a direct link through my family, I felt I didn’t have the right to write poetry about it. But the idea wouldn’t leave me, and when I watched Jeremy Deller’s film that’s referenced in the poem – The Battle of Orgreave – it gave me my way into it, because it’s making a point I also want to make, that things get re-enacted and happen over and over and we’re all complicit.

I suppose for some of my generation, maybe things like film and re-enactment are our way into talking about politics and history.

Division Street

TSOTA: Where did the idea of writing poetry come from for you?

HM: I’ve no idea. It must have been early because I always loved being read to, and I think I developed a love of language as spoken. My Mum says I used to dictate poems to her when I was little. And then my uncle [poet Graham Mort] was very supportive of me.

Probably the most significant thing was when I entered the Foyle Young Poets of the Year and was one of the winners. The prize was an Arvon course, which was a great opportunity to meet other writers and work with established poets. That gave me such a boost when I was a teenager. From then on, I always thought I’ll keep writing, and that gave me confidence, which is why it’s important to build young writers’ confidence and encourage them.

TSOTA: Why do you think it’s so difficult for poetry to get an audience today?

HM: One of the problems is people perceive that a lot of contemporary poetry is not for them. Sometimes, when they hear or read things that they have a connection to, it surprises them.

I’ve done some mad things as Derbyshire Poet Laureate. We went to Morrison’s and read to people and it’s amazing how many said, “I didn’t think I liked poetry, but I enjoyed that”. It’s not because my poem was special, it was more about finding a way of communicating that didn’t seem off-putting. It isn’t a matter of dumbing down, it’s finding the right way to get it across and making connections with people.

My ideal would be to write poems that appeal to people who are interested in books and language, but don’t think they like poetry. I think there is a perception of difficulty, and it’s about saying poetry can be difficult, but it’s a rewarding difficulty.

TSOTA: What motivated you to develop novel-writing alongside poetry?

HM: I didn’t try to write a novel, it insisted itself. I had this idea for a storyline and a series of characters in my head for about a year and a half, and the characters started to live and breathe and talk to one another. I carried this around with me with no intention of writing it down until it got to the point where I thought, “I’m getting a bit obsessed”. As I started to write, I realised it was also a way of taking pressure off myself and enjoying writing again, after having a first collection that got more attention than I expected. I think that can create an expectation and a bit of a fear. It’s that difficult second album thing. I don’t have anything to live up to as a prose writer.

I also like to have a new challenge. Actually, I found writing the novel worked in parallel with some of the poems I started writing for this second collection, because it shares some concerns.

TSOTA: Do you have any other projects in hand?

HM: I’m editing a book of women writing about adventure and landscape with two other writers. Completely separately, I’m writing a trail-running guide to the Lake District. That’s a completely different kind of writing to what I normally do. There are lots of things in the air, which is how I like it!

Mike Farren

Helen Mort’s Website: http://www.helenmort.com/

Leads to Leeds Website: http://leadstoleeds.com/

Helen Mort’s Email: [email protected]

Helen Mort’s Twitter: @HelenMort

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: author, Battle for Orgreave, Blank Page Industries, Chemic Tavern, Division Street, Flamenco, Graham Mort, Helen Mort, Ian McMillan, interview, Jemima Morrell, Jeremy Deller, Kim Moore, Leads to Leeds, leeds, Leeds University, Leeds Young Authors, Peepal Tree Press, poetry, Sam Moore, We Are Poets, Word Club, writing, yorkshire

Comments