Joanne Coates: Artist, photographer and the UK Election Artist 2024 – interview

October 3, 2024

Joanne Coates, image credit: Jack Moyse

Joanne Coates is a visual artist and photographer based on the border between County Durham and North Yorkshire. She is known for her work exploring class, gender and gentrification in rural, working-class communities. I joined Joanne (and her gorgeous sheepdog Glenn) for a chat about her work.

“I don’t like calling myself a photographer because I think it limits me to what I’m allowed to do,” says Joanne. “But photography is how I’m able to tell stories: it’s always there – everything else revolves around it.”

Joanne grew up in rural Yorkshire, and left school after her GCSEs. She was introduced to photography on a an Access to Higher Education Course and went on to a fine art foundation course and then a BA in photography at the London College for Communication, but a combination of her career and the prohibitive cost of London living led her back to rural spaces. She is now based on the border of the North East and Yorkshire.

With this in mind it would be easy to draw a connection between Joanne’s own background and the easy affinity she seems to establish with the communities she documents. However, when I talk to her, she wonders whether it’s her experience of not quite belonging that makes her such an effective collaborator.

As a child she lived with different family members between Gisborough, York and Swaledale. “Even though it isn’t a big geographic triangle, I never really belonged to one of those places,” she says. “Sometimes people go ‘Oh, you’re the insider’ – and I’m not really.”

“It’s just connecting with people – when you’ve never had a specific home, maybe that is what you do quite naturally.”

A photograph from Middle of Somewhere, Joanne Coates

When Joanne was selected as the Election Artist for 2024, she proposed a project looking at the election from the vantage of decentralised communities, both rural and urban, across the UK.

Several days after she found out, the election was called. “Usually I do so much research,” she says. “This was like: ‘Okay – you’ve got two days to do this.’”

The final artwork still needs to be approved by committee, but part of the project involved travelling up and down the country with an “honesty box” into which the people she met could post their honest responses to questions like: ‘What does democracy mean to you?’ or ‘Why is voting important?’.

“When you see an honesty box, even though you’re getting a product, the principle is that you trust other people,” she explains. “[I wanted] to have those conversations built on trust and for people to be able to share openly.”

The box was painted pink, a colour she chose for its neutrality. Joanne is clearly a politically-engaged person, so I wonder how she feels about the requirement to remain neutral?

“It’s a difficult one because I think artwork is built on subjectivity,” she says.

“A lot of the groups that I’ve worked with in the past have quite complex politics because of their backgrounds, but I would always be very open about working with people. You can be neutral but critical.”

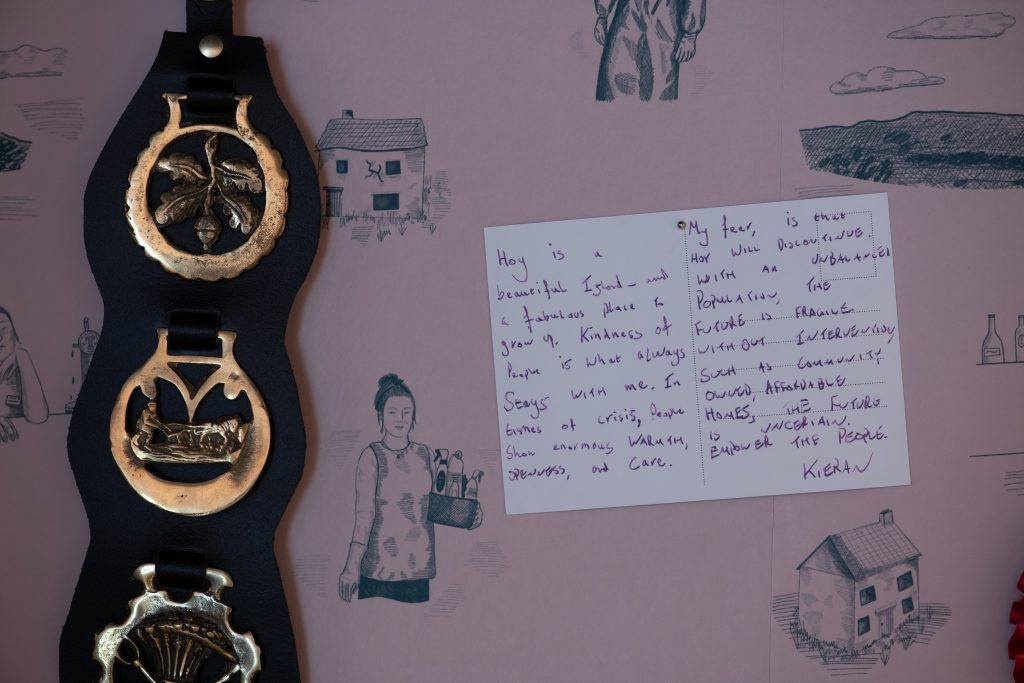

Aisling, one of the women Joanne worked with for Middle of Somewhere, photographed at home in Hoy, Orkney

Joanne’s solo exhibition, Middle of Somewhere, is showing at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead till November and came about after Joanne won the 2024 Vasseur Baltic Artist Award. Building on previous projects The Lie of the Land and Daughters of the Soil, the exhibition is an assemblage of photographs, sound, film and installation documenting life in Orkney and the Yorkshire Dales through the ‘lens’ of young women from those communities, all grappling with the question of whether to stay or go.

A wooden bus shelter forms the focal point of the exhibition. Wallpaper depicting women at work serves as a backdrop for postcard-musings from locals, and in the corner an old TV plays the voices of the women Joanne worked with over new and archival footage of the areas. I wonder what gave her the idea?

Middle of Somewhere, Joanne Coates

Detail from inside the bus shelter, Middle of Somewhere, Joanne Coates

“Something that Aisling [one of the young women she photographed] really stuck with me,” she says. “There’s a lack of third spaces. Even waiting for a bus … waiting for a ferry… There’s nowhere to sit. You’re stood in the cold.”

I wonder if the absence of third spaces (broadly: places that are neither work nor home) is something Joanne relates to within the creative sphere?

She says that the function of what should be third spaces for artists is negated by an overwhelming emphasis on networking. “We’re taught to be like businesses,” she says. “Does that mean that we lose the collaboration between artists? My worry is, it’s making this more cutthroat industry in a time when we all need to come together more.”

Another key concern for Joanne is accessibility in the arts. Joanne is autistic and has ADHD, something which she is beginning to explore in her practise, beginning with her pieced Bedding Up in MIMA’s exhibition Towards New Worlds, which presents pieces from fifteen disabled, D/deaf and/or neurodiverse artists exploring their experiences of the contemporary world.

“I had talked to [the curator], Aidan Moesby, about how I’m not always open – or I don’t know how to be open -about the fact that I’m Autistic and I have ADHD,” she says.

“Especially in rural spaces, there is quite a big stigma around hidden disability, because your value is attributed to your work,” says Joanne. “The work that I did was about stimming and manual things that keep me going. Farm labour is a job gives me routine, whereas in the arts I don’t have much routine at all.”

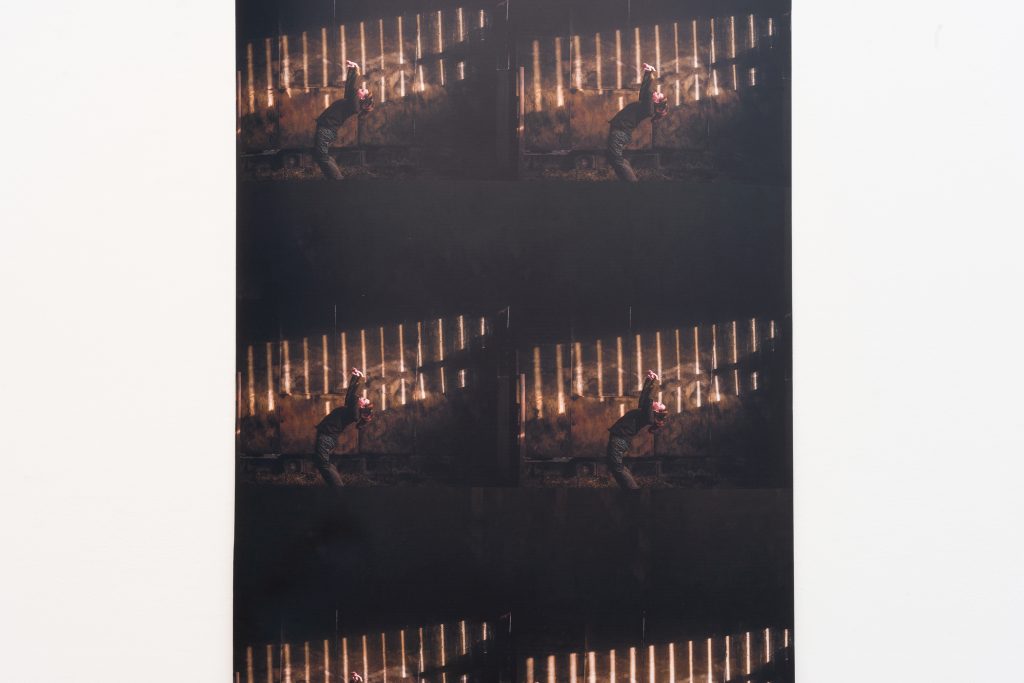

The result is ‘Laborious, Bedding Up’ a series of ethereal self-portraits accompanied by a pair of dungarees gifted to her by a fellow farm-labourer. The portraits are printed on a strip of wallpaper and show Joanne leaning back, arms raised in release, illuminated by the slatted light of the barn. The repetition of the pictures mimics the rhythms of farmwork itself, but Joanne was also interested in the implications of the care farmworkers like herself show to animals. “They like being together,” she says. “You wouldn’t make a loud noise around them; you would make an allowance for how they move across the field – but we don’t do that with humans.

‘Laborious, Bedding Up’ by Joanne Coates, from Towards New Worlds at MIMA

Detail from ‘Laborious, Bedding Up’ by Joanne Coates at MIMA

“If someone finds loud noises difficult, we don’t make an allowance for that person. It’s experimenting with all those things.”

Joanne tells me she was diagnosed in 2018, and support from the government’s Access to Work scheme has been pivotal for her. For example, prior to our interview she had two hours of body doubling, in which a support worker accompanies her while she completes difficult tasks which she might otherwise avoid.

“It’s partly cynical, because the whole point of it is: ‘disabled people need to work’,” she says, “but before I had Access to Work, I couldn’t function as an artist.”

A recurring theme in our conversation is how difficult it can be for artists, especially those who are disabled, working class or living rurally to continue their practice, attend relevant events, and find the space to think creatively while managing to sustain themselves financially.

Joanne has clearly enjoyed a lot of success lately, but farm work is still a necessity. She says part of the difficulty is the installment structure used by galleries. “You might get a little bit at the start – that goes on all your materials. You’ve still gotta pay your bills,” she says. I ask what she thinks could be done to help?

“If they had a basic income, you wouldn’t have to work other jobs that are unsustainable,” she says, alluding a model that sounds similar to the Basic Income for Artists (BIA) that Ireland launched in 2022, whereby 2000 creatives are being paid €325 a week over a period of three years. “You [would] have time to play and to make and to create.”

Joanne is also doing her own bit to help other rural artists. She is director of Roova Arts (formerly Lens Think) alongside her partner Dan, an organisation through which she hopes to help working-class creatives from the North East and North Yorkshire through events like their upcoming artists social in October and eventually residencies.

“There’s a missing factor of rural art spaces who take care of artists who are already there,” she says. “You always need an international network but if you ignore who’s out already there, that’s equally as problematic.”

Beyond resources, this is about changing attitudes.

“There’s amazing artists across the North of England and sometimes when you say you’re from the North you’re not taken seriously,” she says. “It’s time that we see this as a place where artists can flourish and thrive and they’re important.”

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: art, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, interview, MIMA, photography, politics, uk general election

Comments