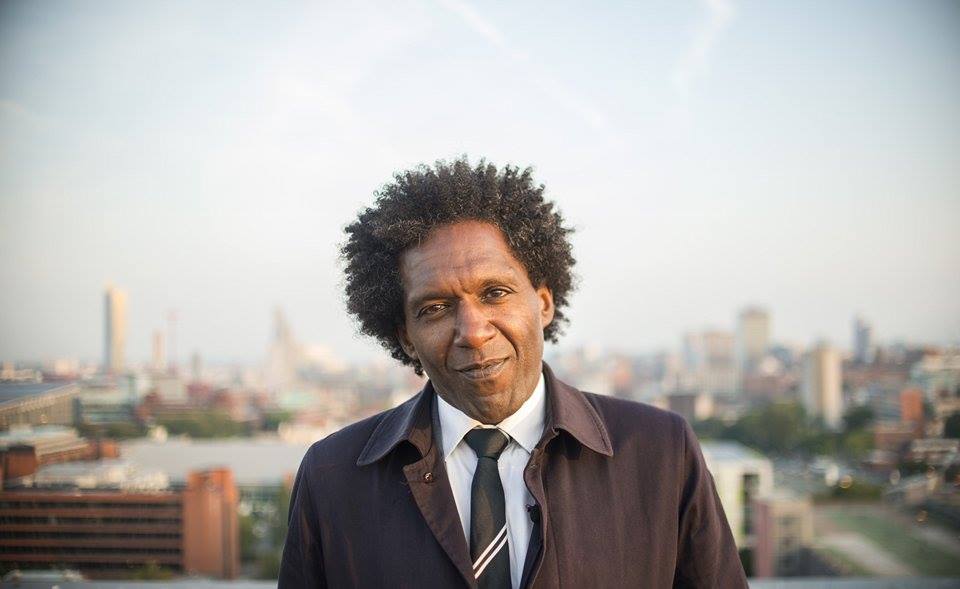

Manchester Literature Festival welcomes the return of award-winning poet and University of Manchester Chancellor Lemn Sissay to headline a celebration of diversity in writing following The 8th Black and Asian Writing Conference. Sissay’s return to Manchester, “the city where he belongs”, went accompanied by a short series of monologues from Cultureword competition writers about family, adoption and identity.

Lemn Sissay walks out onto the Contact theatre stage following monologues from the Cultureword competition writers, holding his newly released book, Gold from the Stone in hand. It feels like a homecoming for the poet whose words line the streets of the city. Sissay begins: “I belong here”. His distinctive Lancashire tone fills the theatre, and one cannot help but be immediately captivated by the words of the wordsmith in the city where they were formed. Sissay, raised a child of the state, explains how his poems have always been like his “flags in the mountainside”, a way of capturing and showing the things that have happened to him.

The story of Sissay’s upbringing in Lancastrian foster care has become well documented since his appearance on Desert Island Discs. In 1966, Sissay’s mother Yermashet had been able to afford to move to England from Ethiopia due to Haile Selassie’s idea of imperialism. On arrival Yermashet had discovered she was pregnant. The news of pregnancy was not welcomed. Yermashet decided to name her baby ‘Lemn’, which means ‘why’ in her native tongue. Lemn Sissay was put in foster care so that Yermashet could pursue her education. Sissay’s fostering was treated as an adoption, and he lost all identity when his social worker, Norman wished his own name upon Sissay.

Early years of rejection and isolation have left Sissay with emotional scars, but they have helped shape him as the person, poet and artist he is today. “We have to see each other, and acknowledge each other, and be kind to each other”. Sissay is wearing a t-shirt bearing the slogan ‘inspire and be inspired’. Inspiration defines the ambition that Sissay has bought to his role as Chancellor of the University of Manchester. Sissay recalls a conversation about the value of inspiration that took place between him and Brian Cox on his day of installation. The example of graphene’s discovery in the University’s laboratories using sticky tape and a pencil is used to illustrate Sissay’s point that “inspiration is economically quantifiable”.

“How strong. The night lies

As light aerates the dark

And atomic dreams multiply

From a graphene heart”

Lucy Miller-Sheen, the first of the Cultureword competition writers, opened the evening’s proceedings for Sissay. Sheen delivered a monologue expressing the sense of cultural displacement and linguistic disenfranchisement that had been synonymous with her childhood as an adopted Hong Kong national raised in Britain in the 1960’s. Adoption had stolen from Sheen all the little things that a person should take for granted, such as the answer to the question ‘where do you come from?’ Sheen declared how she felt “too English to be Chinese and too Chinese to be English”. Everyone with a home is tied to a line “like a stick of Blackpool rock”. Yet at the orphanage there is no line, it is simply a beginning. The day Sheen was adopted she felt unidentifiable, the Hong Kong English child in her had died. Sheen closed her powerful monologue by delivering the reflective line: “The end is the beginning, the beginning was the end to where I was lost and found”.

Claire Hynes followed Sheen’s dynamic curtain raiser. Hynes brings a monologue to the microphone: “I had a dream last night, it felt so real it was like living in a parallel world”. The analogy of the dream is used by Hynes to convey to the audience the disproportionate amount of public attention her “plain old boring family” has been receiving. Hynes is struggling to come to terms with the attention, as there is “no emperor’s new clothes business going on” with her family. Hynes finished her maternal monologue by revealing that she has non-identical twins differing in complexion, “but that’s the way it is”.

There is something cathartic about the way the Cultureword competition winners deliver their monologues. Each speaker walks deliberately into the spotlight and releases a tender well-calculated monologue, which voices suppressed emotions through the adoption of poetry. Yet all moments of levity that break through the intense emotion of the monologues are comically captured by the accomplished performers. Christina Fonthes purposefully approaches the microphone after Hynes’ monologue with a similar moment of lightheartedness: “I had to get the coach, as Richard Branson wouldn’t let me get the train”. She soon, however, falls into emotive subject matter, divulging to the audience the story of traveling to London to reunite with her distant mother, who she had not been in communication with for two years. Fonthes used a James Baldwin quote in her monologue that appeared to resonate with many of the audience: “People don’t let go of their anger because they are scared of the pain it will let in”.

Seni Seneviratne – the last of the Cultureword competition writers – finished the evening’s opening monologues. Seneviratne strolled onto the stage singing Nat King Cole, with an absorbing presence that instantly captured the audience. Seneviratne’s monologue addresses the sentiments that had been synonymous with the death of her elderly parents, closing with the profound exclamation that, “the greatest thing you will ever learn is to be loved and to love in return”.

Comments