Photo: Izzy Hebb

I don’t think it’s controversial to suggest that many in Leeds’ cultural sector perceive a serious disconnect between the city’s planning function and its independent spaces that nurture communities of creative micro-businesses and freelancers. This is coupled with a growing lack of trust arising from an unfolding series of catastrophic losses including the closure of The Tetley, which I co-founded with Pippa Hale in 2013, in December last year, alongside Sheaf Street, CLAY (Centre for Live Art in Yorkshire) and Wire nightclub among others. The creative community based at Aire Street Workshops is another currently fighting for its continued existence, a case well documented in the media. Back in 2011, when we first viewed the building that would become The Tetley, the idea of a regenerated ‘South Bank Leeds’ was newly emerging.

The closure of the historic Tetley brewery and availability of plots south of the city centre created a unique opportunity, first identified by Leeds Sustainable Development Group, to rethink the expansion of the centre and to unify these sites within a singular vision. When a report on the Council’s South Bank Planning Statement went to the Executive Board in July 2010, it came with the assurance that ‘cultural uses, especially those maximising the potential of refurbished local heritage assets, would be strongly encouraged in the South Bank, within and around the City Centre Park’.

This desired synergy between heritage assets and contemporary culture undoubtedly eased the development of The Tetley within the repurposed 1931 Directors’ Offices. The October 2011 Planning Statement went further in specifying ‘cultural and community’ uses deemed appropriate by the Council: ‘These may include uses such as small-scale healthcare, childcare or other community facilities. Cultural uses may include galleries, museums or visitor centres’. Fast forward to 2024 and the phased arrival of ‘Aire Park’,

While a significant part of the South Bank area which, having asset stripped the cultural capital hard-won by The Tetley over the 10 years of its existence (including its name, something we gave the building) it is now virtually devoid of the spaces for culture and community envisaged back in 2011. What does remain? The co-working spaces at Duke Studios and new public sculpture Hibiscus Rising by Yinka Shonibare, commissioned as part of the Leeds year of culture – none of which are the work of the developer. nobody could have predicted the multiple shocks that have impacted upon every aspect of public and private life over the last few years, this dissonance matters. It matters because it brings into question the processes by which our city imagines its future, the stories we tell ourselves about that future, and the strategic alliances we build in service of that vision. What faith can we have that arts and culture will be considered within the city’s development and its ambitions for ‘inclusive growth’?

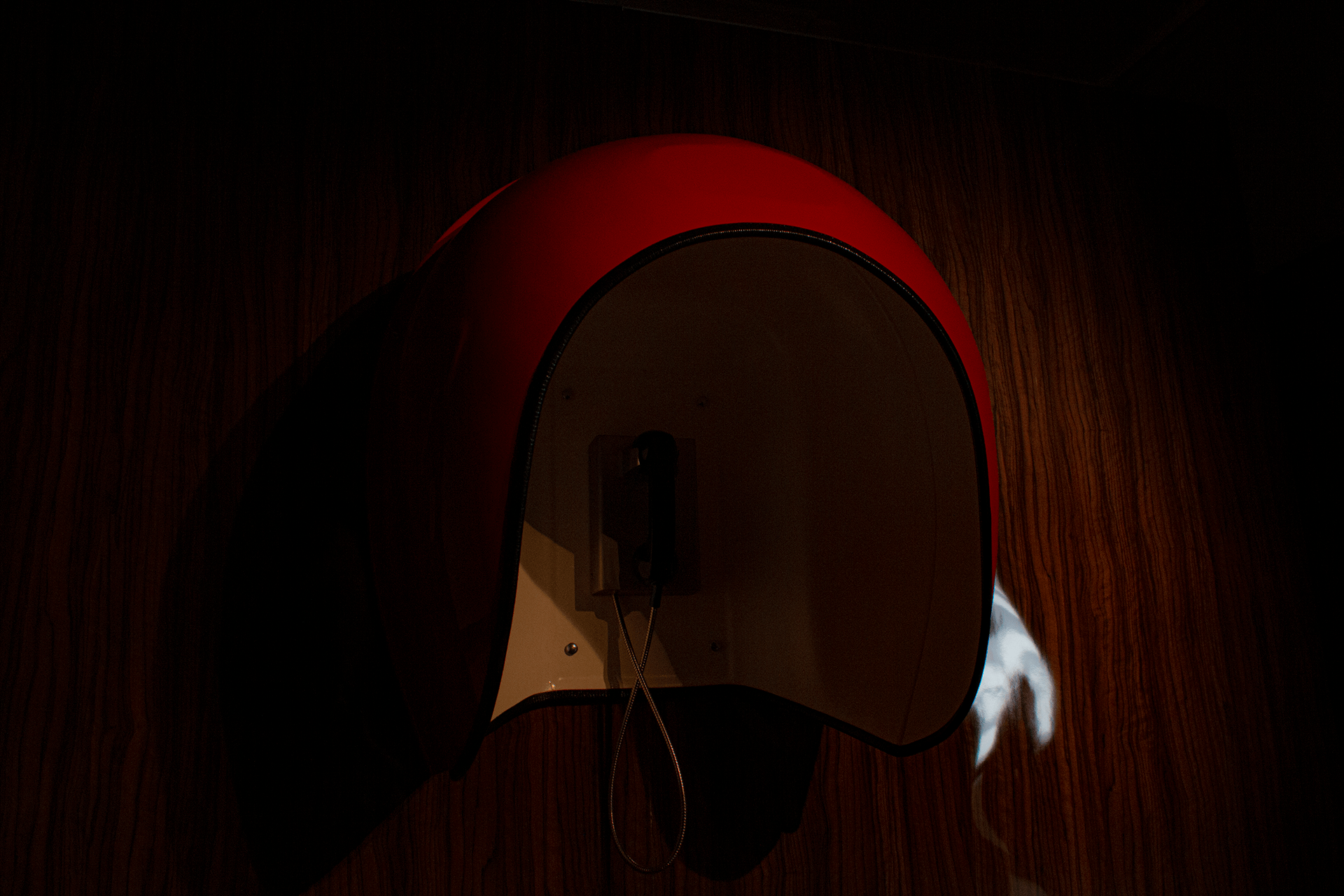

Jules Lister, ‘Collective Recording’. Organised by artist James Thompson, The Tetley, 7 January 2024.

These things matter because levels of property ownership among the small-scale creative sector are chronically low, an issue that is being explored by No Space Left To Play, a new alliance of creative partners in Leeds. Without certainty of tenure, independent creative initiatives are kept perpetually precarious and unable to reach their full potential amid the evolving topography of the city. It matters because Leeds has thousands of creative graduates who will now emerge into a city where the potential of a sustainable creative career feels more constrained than at any point in the 34 years I’ve lived here. Many brilliant creative spaces in Leeds have been founded by people who came here to study. Can we promise today’s graduates the same opportunities?

Pervesely, the catastrophe of The Tetley’s closure seems barely to have registered on the civic level, at least in anything articulated publicly. Interviewed by the BBC in April, Director of Leeds Civic Trust, Martin Hamilton, commented largely positively on developer Vastint’s vision for Aire Park before adding, “There is a slight disappointment it wasn’t possible to retain a gallery use on site though, this is a huge commercial site and having one pocket as an independent not-for-profit function seems to the Leeds Civic Trust like it could have been a better way of doing things.”

Are we, cultural workers of Leeds, so insignificant that the erasure of our achievements register only as a ‘slight disappointment’? Never mind the millions of pounds of public money invested, the years of hard work by so many, the livelihoods lost and businesses displaced when the building closed. Never mind the many artists supported by The Tetley, the creative careers of staff nurtured, leading to roles at The Hepworth Wakefield, Channel 4 and the British Library among many other cultural institutions across the UK. The staging of Yorkshire’s only Turner-prize winning exhibition. The audiences welcomed, the families and children who came to play the friendships celebrated over Sunday lunch and the creative plots hatched in the bar.

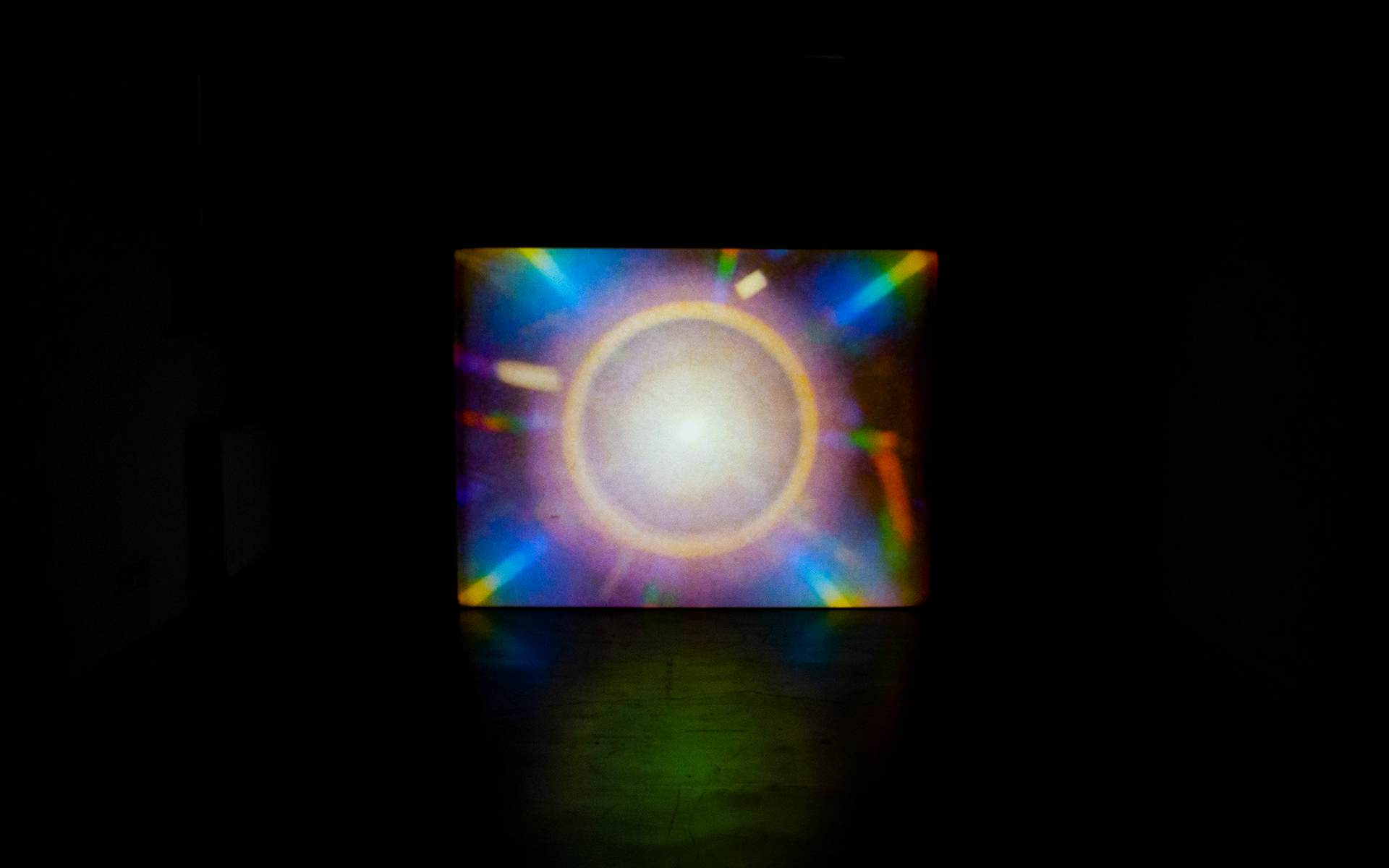

Mel Brimfield, The Giant Despair, 2021 @ The Tetley

Why aren’t the messages about the value of small scale cultural assets getting through? If they’re getting through, why aren’t they sticking and being placed up front and centre in Leeds’ approach to urban planning, not just in the centre but right across the city? Leeds has world-leading research institutions and a Centre for Cultural Value publishing millions of words annually on the value of arts and culture and the role of artists in society and placemaking. In 2016, the AHRC Cultural Value Project published its final report, in which the authors questioned the impact of major cultural buildings in urban regeneration, claiming, ‘Far more significant might be the effect of small scale cultural assets – studios, live-music venues, small galleries and so on – in supporting healthier and more balanced communities’. But we’re losing these very venues at an alarming rate. Meanwhile, the loss of so many cultural spaces in Leeds over the last year or so continues to ripple out well beyond the city. Our reputation for nurturing independent, home-grown creativity is at risk.

The Tetley rebranded last week as Yorkshire Contemporary: the organisation’s search for a new home continues and may now lie beyond Leeds. What a loss. To quote photographer Peter Mitchell, ‘Nothing lasts forever’. But maybe some things should last a good long while and be allowed to find their feet, to blossom, to deepen their connections and generate shared cultural riches as public goods. Leeds once again has no independent contemporary art space at scale in the city centre, taking us back nearly 20 years to the situation circa 2006, the year Project Space Leeds [PSL] was founded with a mission to tackle this very absence, leading ultimately to the creation of The Tetley. Under the leadership of Pam Johnson, Head of Culture Programmes for Leeds City Council, Leeds will soon begin the process of putting in place a Cultural Compact of the type that already exists in many other cities including Hull, Sheffield and Wakefield. In recognition of the radically altered environment for culture and the acute need for new models, the ‘Compact’ framework brings together cross-sector partners ‘driven by a shared ambition for culture and place, to co-design and deliver a vision for culture within a place’.

Like many local authorities, Leeds City Council is reeling and on the brink from too many years under an enforced politics of austerity. We need new alliances, new ideas and new action to collectively address how we can reverse the current decline of small-scale spaces for creativity in Leeds. Many of us want the same things: a more just, equitable and accessible city brimming with vibrant creativity. But right now we don’t have the balance of power right when it comes to artists and commercial development. I hope the Cultural Compact, and the great work that No Space Left To Play and others are doing to explore and cultivate alternative models of collective ownership, can be the vehicles to finally realise that vision.

Mel Brimfield, The Giant Despair, 2021 @ The Tetley

Filed under: Community

Tagged with: aire park, clubs, cultural venues, development, Gentrification, leeds, Leeds art, leeds city council, leeds culture, leeds culture strategy, sheaf st, The Tetley, venues

Comments