Let’s Talk About Death – death: the human experience @ Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

April 13, 2016

The plague doctor’s mask.

Last month, a shocking pink banner circulated Bristol. Adorned with a colourful moth and an unthreatening green skull, ‘Death: The Human Experience’, it read. Advertising Bristol Museum and Art Gallery’s most recent exhibition, the colourful design attempted to rebrand the morose subject of death.

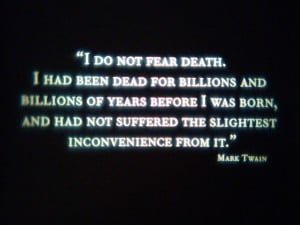

Outside, as tulips began to emerge in concrete cracks and the spring sunshine finally appeared, one corner of the museum remained shrouded in darkness. The exhibition space was split into 5 sections; the first, with blood red walls, discussed cross-cultural symbols of death. Dark, classical music filled the air, as I came face to face with a framed x-ray of a human skull. Reflected in the glass, my own face was faintly visible through the white bones. My immediate reaction was to wonder how similar this skull was to the one safely nestled beneath my skin. My second was to consider my own mortality. “Let’s talk about death” a large sign above my head encouraged.

[pullquote]Tucked discreetly around the next corner attitudes towards death were presented for debate. Considerately hidden between wooden panels at adult eye-height were artefacts and dialogues regarding disease, murder, suicide, sacrifice, infanticide, and timely death.[/pullquote]The short passageway was a shrine to morbid curios: a plague doctor’s mask, taxidermy, a scale imitation skeleton. The collection displayed the ways in which the living deal with the dead – everything was natural in a perverse sort of way, overtly decadent, or aesthetically gothic.

Creeping around the corner shone the bright lights of the second section of the experience. Enter the practicality of medical science; here began an educational journey into the stages of death. On the right were mock morgue freezer doors, hiding informative plaques. On the left was a mortuary set, sterile and white. I learnt about the multifarious ways in which the dearly departed are dealt with around the globe, the physiology of death, culture-specific post-mortem preparations of the body, decomposition (and preventing it), formalities and legalities, the choice of containers in which the dead are placed for final rest. I was surprised at how much of this information was entirely new to me, and learning about it didn’t feel vulgar or distasteful at all.

Tucked discreetly around the next corner attitudes towards death were presented for debate. Considerately hidden between wooden panels at adult eye-height were artefacts and dialogues regarding disease, murder, suicide, sacrifice, infanticide, and timely death. Whilst not the most pleasant of topics, they are important issues, and I am grateful to the museum and exhibition curators for including this section. The most striking relic: the skeletal remains of a 13 to 14 week old human foetus, dated within the late 1900s. With its missing arm, eerie grin, and alien-shaped skull, this well preserved homunculus would have once been used as a training aid for future medical professionals.

Re-emerging into the light, the next section dealt with human remains, whilst displaying none. A glass cabinet boasted an odd assortment of artefacts normally buried alongside those who take their final rest beneath the ground. There was money, mostly from the east, to be spent in the afterlife, a pair of bright, high-heeled shoes for dancing with [the] god[s], and, the most unexpected of all: a mobile phone. This item, according to a funeral director interviewed for the exhibition, has become increasingly popular, just in case the departed need to get in touch post-burial… In Victorian times, a bell was commonly placed inside mausoleums; whilst the apparatus for communication has modernised with the times, an irrational fear that the living are mistakenly buried as dead has evidently not subsided.

In addition to an array of coffins and tombs, cremation urns were also included; the most interesting of which was a biodegradable urn, filled with seeds. The person’s ashes are placed into the urn, which is buried in fertile soul, and together they become new life in the form of a tree. Having read about the inception of these years ago, it was good to see this eco-friendly option available on the death market!

Also explored in this section were funeral traditions across the globe, which, by this point, I was unsurprised to learn are entirely varied. Many cultures mourn excessively, with extended periods of remembrance, and wearing black. Others treat one’s passing as cause to celebrate the life, rather than grieving the loss. In comparison to many, the English traditions seemed very formal and sombre, and I wondered if this was the cause or effect of our historically detached relationship with death.

Around the final corner, again diverted from the main space, was a section on science and ethics, which offered the subject of euthanasia up for debate. Once again, I was glad that this difficult topic had not been omitted. With a lot to consider I stepped into the final, reflective space – a softly lit, calm area, filled with seating, notepads and reading material.

In ‘The Hour of Man’, nineteenth century historian Phillipe Ariè asserted that death had become “improper, like the biological acts of man.” He continued: “a new image of death is forming: the ugly and hidden death.” As evidenced by the first section of the exhibition, the English have forever explored the theme of death through art and mythology, but in practical terms, it is still commonly considered a taboo subject – one that is excluded from formal and cultural education. By shining a bright, unfaltering light on the subject, ‘Death: the Human Experience’ destigmatises Ariè’s “ugly and hidden”, exposing, instead, a universal, and ultimately final, event that affects every life at least once. I took many things from this fascinating exhibition, but most of all, that it is perfectly natural to talk about death.

Comments