On the evening of the 27th of July, 1890, the haggard old figure of a man made his way through the streets of a small French town, Auvers-sur-Oise, a bullet fixed in his belly. This man was Vincent Van Gough. He lay on his death bed at the Auberge Ravoux for two days until he left this life, his death pronounced a suicide. A verdict Loving Vincent analyses, unpacks, and reviews.

Set a year after his death, Loving Vincent follows the journey of the son one of Van Gough’s old friends, Armaund Roulin, a disdainful idler who is given the task to deliver a letter left by Vincent Van Gough. Early on in his quest, Roulin receives the news that the intended recipient of the letter, Van Gough’s father, is now dead. Roulin, now impassioned by the mystery surrounding the infamous artist, follows the journey Vincent Van Gough took in his last moments of life to try and find an alternative recipient of the letter. A death which only becomes mysterious due to the extreme conflicting opinions about Van Gough, and so in trying to deliver the letter conducts his own journey to try and uncover some truths of his father’s beloved friend.

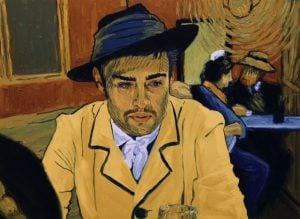

Not only is the film revolutionary in it’s genre of being a crime drama, but one cannot offer thought on the film without addressing the originality of it’s style. Loving Vincent, a collaboration from directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchamn, is the worlds first fully oil painted feature film. A cinematic phenomenon which pushes the boundaries of traditional film and creates something so beautiful, it is difficult to imagine any other style which would be able to justify the telling a tale of an artist so talented, so committed, so legendary. Van Gough’s art has been completely re-imagined in this new world of cinema. 853 shots in the film, 65,000 frames painted in oil paint, and 3,000 litres of paint later, Loving Vincent was born.

Each frame was painted as a full painting on a canvas, then it was painted over for each frame until the last frame of the shot was completed. This leaves you with a canvas painting of a completed oil-painting of the final frame. 853 shots turn into 853 oil paintings which appear in the film. “Everything was a painting on canvas,” says Welchman. “No tracing, no nothing. The opening shot, where we come down from Starry Night, took six hours per frame to paint. So you’re talking about two weeks to do a second. It might have taken 20 weeks to paint that 10-second shot – you’re looking at half a year of someone’s life.”

The passion and creativity that went into creating this film amounted to the glory of it’s subject. The only downfall of creating something with such exquisite aesthetic is how hard it is to present the intensity of the darker aspects of the film. There was no difficulty in watching the fight scenes, the prostitute and man having sex in the street, and the image of Vincent Van Gough struggling through the streets with a gunshot wound; which perhaps takes away from the story’s realism. Yet, the crafting of a film with the same technique as the artist in question ultimately allows the audience to see the world through the same vision Van Gough had for it. One can appreciate the gorgeous french streets, the river boat, the run down hotel that Van Gough walked past every day and not have ones own subjective interpretation on it; you see what Vincent saw. Van Gough could find the beauty in everything, he saw the light even in the darkest of times; something which could not have been accomplished with any other style of film.

The cast, not only exceptional for their talent but also their likeness to the people they were portraying. “Whenever a new character is introduced into the film, they are found in the position in which Van Gogh painted their portrait,” making the film as true to Van Gough as could be imagined. Douglas Booth, who plays Armaund Roulin, adopted a sort of cockney nipper persona to portray the troubled Roulin. A man who makes his journey finding out what happened to Vincent Van Gough into a sort of self renovation.

Whenever cast not from the native language have to play real character, there is always a difficult decision the director must make. Kobiela and Welchamn decided for the actors to each use their natural accents, a technique which avoids any disappointment to fulfil the French tone. The real voices play real people, something which works in the film’s favour.

A unique celebration and retelling of an artist’s life, one told in a new style that I am assured will be re used in time to come.

If you would like to catch Loving Vincent at the pictures, head to HOME mcr’s website for more information: https://homemcr.org/

Filed under: Film, TV & Tech

Tagged with: crime drama, drama, film, HOME, homemcr, Loving Vincent, painter, vincent van gough

Comments