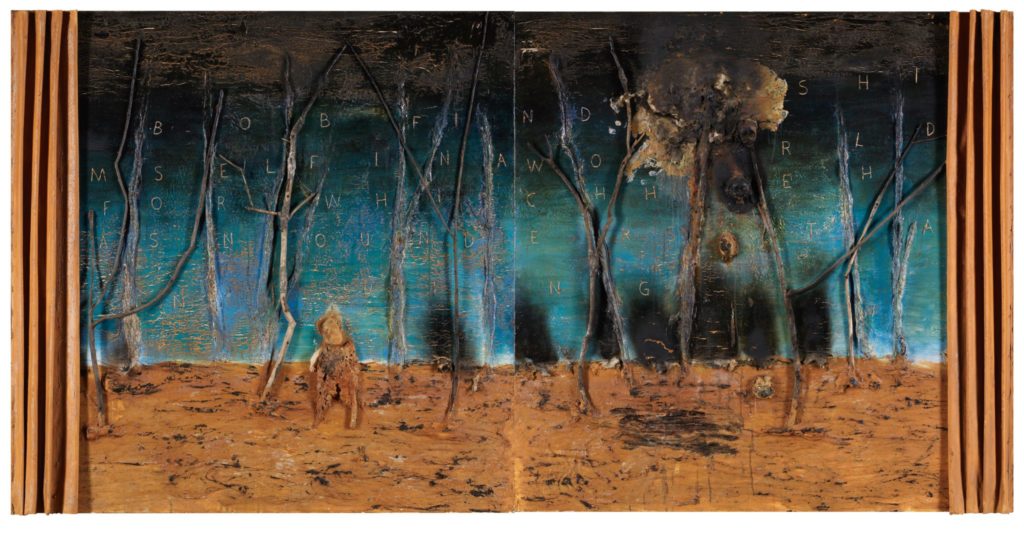

‘BOB FINDS HIMSELF IN A WORLD FOR WHICH HE HAS NO UNDERSTANDING’, 2000, David Lynch

What is it about David Lynch that draws in fans from all over the world, causing them to elbow their way through the crowds to see his paintings, when he’s actually best known for his films? Is it the same reason that the adjective ‘Lynchian’ can now be found in the Oxford dictionary? Given that even HOME’s exhibition brochure itself refers to the show as “weird and wonderful”, perhaps the real question here is – why do we love the “weird” and what is it about things we can’t quite understand that entices us so?

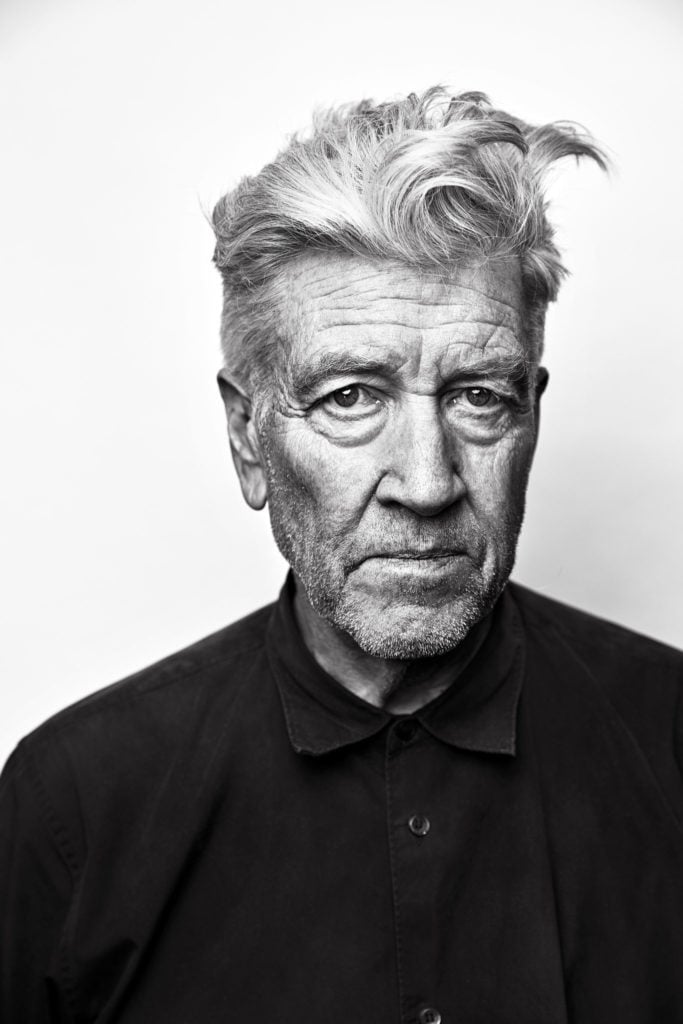

Whether or not you’re a keen follower of David Lynch’s artistic output, you’ve probably heard of ‘The Elephant Man’ or at the very least seen his indestructible hairstyle that resembles Hokusai’s ‘The Great Wave Off Kanagawa’. It’s not necessary to come to this show armed with a folder of neatly organised notes on his life and art, but it does help to be familiar with a few films (one is not quite enough, it will only leave you confused) to get to grips with the artist’s stylistic nuances and obsessions. From the ever present dramatic interior lighting, endless cups of coffee, to mysteries lurking beneath layers of more mysteries and… rabbits.

Let’s quickly run through the most important facts to know about Lynch and his past in the context of a show of his paintings. He began studies as a visual artist and produced still images, before realising that video can essentially be a ‘moving painting’ and so began his nightmare-inducing love affair with film. His career as a director earned him a reputation of a creative genius, and what was previously appreciated by a more select group of movie buffs has now begun to seep into the mainstream. Lynch himself is now done with film and has gone back to staying in and painting in his studio home in LA.

©Josh Telles

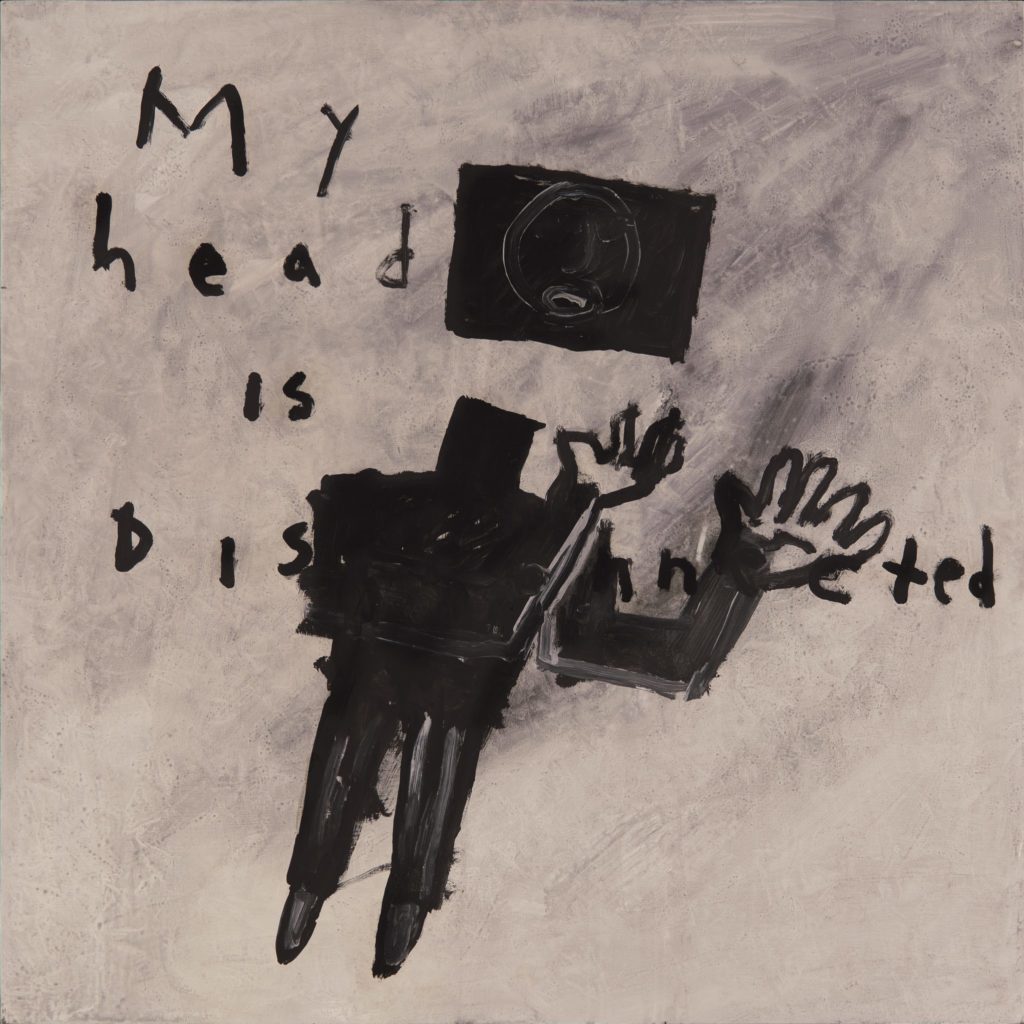

‘My Head is Disconnected’, which also happens to be the name of one of the paintings unsurprisingly depicting a figure with a floating head, is divided into 4 ‘chapters’. This is a useful curatorial tool and a good attempt to tame the chaos left in your mind by the work itself, but the curation never overpowers the pieces on display. The work is simply so strange that the way it’s displayed becomes almost irrelevant, and maybe taking a step back is what all good curation should do to let the work really speak for itself. The exhibition isn’t enormous but absolutely enough to satisfy a viewer hungry for an experience coloured by dystopia and bewilderment.

Now, on to the paintings themselves, although it’s safe to say, they’re best experienced at first hand. Most are large-scale: with sculpted elements made from unknown but unsettling substances, visually dangerously close to bodily fluids; impasto paint and wonky words scratched into the surface with some pieces are even adorned with lightbulbs. Warmly coloured lights are seamlessly incorporated into the canvases alongside twisted characters with long limbs and names like Bob (Twin Peaks anyone?) expressing their thoughts through short lines of abstract text. The use of lights is not that surprising in the days of slick and complex art installations, but Lynch’s work has a very strong handmade quality. It feels as though he tortured the pieces quietly in his studio, day after day, without the help of 25 assistants as is usually the case today. The paintings probably tortured him too.

‘My Head is Disconnected’, 1994, David Lynch

The exhibition also includes photographs, drawings and lithographs – usually drawn in thick black lines and smoky blurs along with accompanying text. One piece in particular ‘I Find It Very Difficult to Understand What’s Going On These Days’ (2008) depicts a figure on its hands and knees, either mid-tumble or just fallen to the floor with a cloud of blackness coming out of the mouth. The title refers to the text on the piece as well and was a personal favourite of mine, because it expresses exactly what I feel when I read the news or scroll through Twitter. Lynch’s thoughts realised on paper seem to come out unedited – the simplest, unfiltered idea can guide the image and end up holding more emotional power than an entire movie.

Interestingly, David Lynch has been practising Transcendental Meditation for decades now, and, if the artist’s own words are to be believed, he has been freed from the anger that plagued him in younger years and is now truly in love with his life. If this is the case, why is he still producing work that uses hanging figures, loaded guns and dismembered limbs as the focal points? Nobody knows. Lynch himself is far from open about his still and moving imagery and its meanings: “Life is very, very complicated and so films should be allowed to be too.” The acknowledgement of his work’s perplexing effects is as much as you’ll find with regards to explanations.

If all the talk about feeling confused is putting you off the exhibition – please don’t be worry. Right now, the HOME gallery space is not a white cube with questionable, pastel-coloured objects attached to obscure meanings and even more obscure text panels. Confusion here means not really knowing what twisted mind these paintings could possibly come from, but the content of the work itself is actually alarmingly relatable. They seem to address a universal darkness, the basic fears most humans share and express an understanding of the everyday experience as something worth considering and slowing down for. Indeed, this elevation of the domestic to the level of exclusive subject matter is very noticeable and it is something that, ironically, can seem hopeful. Constantly being faced with FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) while scrolling through social media feeds when you’re actually comfortably at home is clearly unhealthy and Lynch shows that out of the mundane and boring can come the most memorable statements.

Photo: Michael Pollard

The artist seems to be a strong advocate of boredom in general, or at least of the everyday thought process. He has previously mentioned in interviews the importance of moments when thoughts can flow freely, while the rest of the body isn’t doing much and the mind isn’t directly occupied. The text scrawled across the top of his painting ‘Mr Redman’ reads: “Because of wayward activity based upon unproductive thinking Bob meets mister Redman”. In the painting, Mr Redman’s body is a red mass of spilled guts or something similarly fluid and bodily, so this painting seems to me the real epitome of where Lynch’s work comes from. When the mind is left alone, it can go to the strangest places.

Most of us can relate to this with our shared passion for productivity and a disgust for the anti-capitalist feeling of boredom. To illustrate – it is just one of the reasons why we often carry our phones and headphones everywhere we go, and the moment an unpleasant thought shows its ugly head we can quickly drown it out with a podcast. Lynch allows his mind to go to where most of us are too frightened to look. Yet if we did, would our minds really be incapable of constructing such dark ideas? Perhaps the real reason why David Lynch’s work, in all mediums, is so popular is because through his art he lives out the fantasies and feelings buried deep within the recesses of the mind and painstakingly draws them out, one long arm after the other, followed by some screaming mouths and vomit.

Last but not least, is humour. The elusive, rarely encountered element in the visual arts is actually very present in the work of David Lynch. It’s not laugh out loud, jokes- written-on-canvas kind of humour (although people did laugh walking around the exhibition) but there is a certain absurdity that comes with the nightmarish visions in muddy colours. Is it supposed to be funny? Is he actually making fun of us and belly laughing at the prospect of being regarded as a misunderstood genius while smoking cigarette after cigarette? We’ll never actually know.

Make of it what you will and take that away with you. And it’s a good thing too, because the Lynchian mystery is one of the last of its kind: it will remain a mystery – that, which cannot be googled.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: contemporary art, david lynch, exhibition, film, Home mcr, lynchian, MIF19, painting

Comments