Kate Genever’s ‘I See You’. Photo: Jules Lister.

A leaded glass window in the Art House foyer frames and partially blocks a visitor’s view into the Migration: International Residency Exhibition that unfolds beyond. ‘Demarcation’ by Bijan Amini-Alavijeh is a window without walls, supported by a single strut. ‘Encumbrance’, a neatly built thigh-high wall of mud bricks in the main exhibition space is its sister work; the wall that ought to house the window, now displaced. In their separation, instead of evoking the domestic comforts of home, the wall becomes a boundary or barrier.

Amini-Alavijeh’s simple architectural interventions introduce concerns that recur throughout the exhibition—a partnership between The Art House and Wakefield City of Sanctuary, initiated by artist Ivan Smith. It shows the work of nine artists (plus two associates) invited to spend a month in Wakefield. Their challenge was to produce work on the ‘migration’ theme. Artists visiting from Belize, Mexico, Iran, and India joined local and non-local UK residents to bring varied levels of familiarity or experience to the theme. Amini-Alavijeh (UK), a recent graduate from Manchester School of Art, adapts formal concerns manifest in previous work as abstract, geometric painting to a more politicised bent by shifting his medium. Encumbrance’s raw material comes from an allotment cultivated by Bryan, a Zimbabwean asylum seeker. Mud, walls and windows provide both practical, physical materials and resonant metaphors. A dual reference to material and symbolic conditions of migration continues throughout the show.

Andy Singleton (a Wakefield native) similarly adopts an existing formal mode, using his signature intricate paper cutting technique to produce Sea Defence, a cutaway-geology-diagram of a sculpture (but representing sea not land). The sculpture and accompanying drawings posit water—like mud—as a global material that both connects and divides. It reminds one of the frequent recent deaths of migrants, drowning in flimsy vessels at sea, making paper’s ephemerality more relevant than simply as a show of technical dexterity. This segment of sea recalls too a flat earth rendition of the world and brings to mind the idea that, like this archaic world-picture, contemporary political views post-Brexit are blinkered or narrowly informed.

Andy Singleton’s ‘Sea Defence’. Photo: Jules Lister.

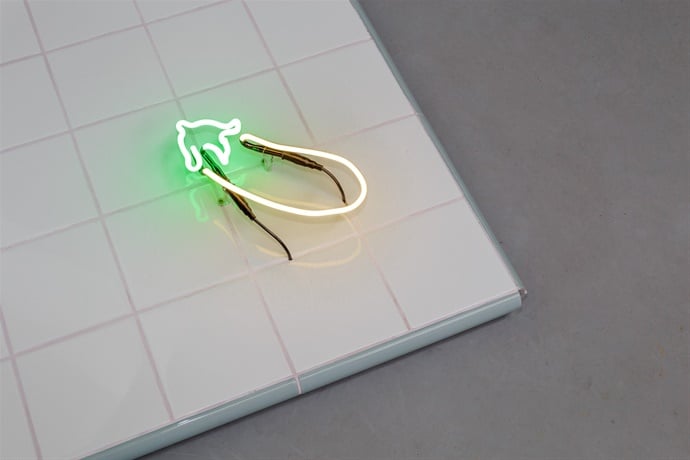

Participating artists received a strong steer by the project’s partnership with Wakefield, City of Sanctuary, who offer support to refugees and asylum seekers. Nevertheless artists were given an open brief. Joe Cotgrave (UK) whose practice explores his status as an HIV positive gay man took migration alternatively as a way of describing biological movement of a virus, depicted in ‘[UD]’ as semi-abstract animations on two mini-LCD screens. Making an analogy between cruising in physical space and digital ‘cruising’ on apps like Grindr, the animations are paired with a tiled, plinth-like construction that suggests a bathroom, clinic, or (as hinted by the sign-like phallic neon aubergine that adorns it) a gay sauna. Associate artist Emily Simpson (UK) also considers the relationship between life on and offline in her mixed media installation ‘Erm…’ A floor-positioned laptop shows seemingly stream-of-consciousness typed messages, peppered with text-speak abbreviations, contemplating the possibility of living in a “massive grey area”. Utterances like: “AVOCADOS, STOP BUYING AVOCADOS” evoke #firstworldproblems, yet the work effectively prompts some reflection on inequality between migration of digital information online and of bodies in the physical world.

Other artists worked with people they met through City of Sanctuary. Juan Cristóbal Gracia (Mexico) paid refugees and asylum seekers £36.95 (equivalent to a week’s allowance from the Home Office) to copy three charcoal drawings. This in itself raises questions about the ethics and the economics of migration, whilst the content of the drawings adds further meaning. They depict the character John Bull (an eighteenth century personification of England), a quotation fictionally attributed to Bull, “Law is a bottomless pit” (also the work’s title), and a sheet of paper totally covered in charcoal. Bull is a legacy of the age of Empire; first designed as a satire but later coming to be seen as a symbol of freedom and loyalty to the king. In each drawing—copied from the previous—the character is degraded, a deterioration that might be interpreted in several ways. The diminishing of an idea (the nation state), the obscuring of a particular political history where a powerful country supports migration when it suits economically, but derides it when it doesn’t. Or it could represent the ‘Chinese whispers’ that occur in migrating communities about where and how is safe to travel. In spite of the global flow invoked by Simpson, information is not equally available to all. The repeated dense black and brown pages in the work’s gridded arrangement are like a void of despair, the bottomless pit of the asylum system.

Joe Cosgrave’s ‘[UD]’. Photo: Jules Lister.

Perhaps wary of parachuting into vulnerable people’s lives, the artists who worked with migrant communities did not place individuals or personal stories front and centre, focusing instead on social or symbolic practices. Kate Genever’s (UK) ‘The Last Thing That’s Necessary But Everything That’s Needed’ almost visualises this approach. A series of photographs show bunches of flowers on wood-effect laminate, institutional tables; people are present but in the background. Like TV documentary subjects recounting traumatic events their faces are cropped out of shot. Affected by the generosity of volunteers who run drop in centres, Genever foraged wildflowers to gift to them. Generosity as a topic continues in her other works that show, for instance, the open hand gestures used by volunteers or the simple phrase “I see you” rendered in neon. However, the disparate formal and verbal language of these pieces makes them less powerful than the simple token of flowers, which Genever will continue by sending flowers to Wakefield’s Urban House, Initial Accommodation Centre, for a year.

Katie Numi Usher (Belize)—inspired by interacting with refugee children—highlights play as a universal impetus that can nonetheless be lost in times of trauma. Ivan Smith (UK) takes food as his motif. For ‘Soup Space’ he cooked soup for City of Sanctuary drop-in visitors at three locations, inviting them to write favourite childhood meals on the white tablecloths. The work is presented here as an installation of the tablecloths, hung like shrouds, plus photographic documentation. These works raise questions as to who the migration project is for: the artists, the migrants who become their subjects or a wider audience encountering the exhibition? The answer might be ‘all of the above,’ but the presumed emphasis differs between works, as intimated in their presentation. Numi Usher’s bright hopscotch quilt lies sullen on a concrete floor; her adult sized wellingtons playing elastics carry an undertow of menace. There are apt formal choices here but the work’s positioning outside the main gallery space (in a room used for workshops and events) demotes these presentational aspects. The inclusion of photos from drop-in sessions suggests Usher’s impetus might be more on participation than final exhibition. For the work to be developed further as a gallery project then—beyond the appeal to a universal relevance—Numi Usher might go on to consider the cultural specificity and particular routes of migration of her chosen games.

Smith’s work, too, happens primarily in its interactions. The work does function as an installation. A viewer can ponder soup’s associations—from comforting meal to soup-kitchen survival provision—and enjoy participant contributions. But its location in a tomb-like side space gives associations that confuse it’s intent. There is scope for development here too in, for instance, cooking and documenting contributed recipes. Still it must be recognised that what the artists have achieved has been realised in only a month. These projects show the artists giving over to the residency process without knowing quite what the outcome will be. This approach is in contrast to the work of Cotgrave, for instance, which has a slick presentation but evidences minimal impact of this particular residency on the trajectory of his practice.

The most sophisticated work in the exhibition by Bijan Moosavi (Iran) effectively unites process and formal outcome, and it is perhaps worth noting that representing intersecting cultural traditions is an ongoing concern in his work. Struck by how The Church of England plays an important role in welcoming refugees mainly from Muslim-majority countries, Moosavi took an old Islamic song and restructured it into a choral format from the Christian tradition. ‘Nasheed Choir’ was performed by local singers at the exhibition launch and framed sheet music copies given to St John’s Church and St. Michael’s Church, Wakefield (venues that work closely with migrants) as well as being included in the show. Regardless of intended generosity art projects can have an inbuilt ‘us and them’ structure, with the artist positioned as outsider to an imagined ‘community’ identified by a particular characteristic (in this instance involuntary migrant status). Conversely the choir—formed through an open call for singers—models an intersectional new community. Participation is not based on a prescribed characteristic and identities are potentially reconfigured through interaction.

In some regards the residency itself creates a new community, albeit a temporary one. This could be what Siddartha Karawal (India) had in mind when making his mixed media installation ‘What’s Cooking’. Using toys sourced from Wakefield charity shops, Karawal deconstructed and rebuilt these objects to be “articulated anew” as anthropomorphised figurines. Appearing first as a crowd that might be equated with groups of travelling migrants, Karwal’s description of the thronging hotch-potch of figures might just as well apply to what it feels like to be an artist as part of a residency community. He writes: “It is difficult at times to discriminate between one idea and the next: some forms only come alive for a fraction of a second before they seem to dissolve again.”

What the Migration exhibition doesn’t fully capture are the conversations and interactions between artists and non-artists, migrants and non-migrants, that have happened as part of the residency process. The residency’s flexible structure enabled Smith and The Art House to respond to opportunities that arose. For instance, associate artists Simpson and Anthony Shepherd (UK) were invited back to exhibit after contributing to a previous Home and Away residency run in 2015. Shepherd’s ‘I Walk the Earth’, made from a wall mounted boot scraper and wooden laths, is well positioned in the exhibition stairway to suggest the physicality of a journey—walking step by step. Also, during their stay, invited artists fortuitously met Iranian film-maker Nader Nahidpour and Zimbabwean artist Bryan Mucheriwa (from the allotment), both now based in Wakefield. Though not represented by artworks, they are credited as contributors in the exhibition hand out and a film by Nahidpour will be screened at a later date.

The residency apparently functions primarily as a development opportunity for artists, encouraging them to explore a socially engaged or attuned way of working that is new to some. Like Amini-Alvijeh’s window—both blocking and framing the view—formalising this into an exhibition inevitably prioritises certain aspects of the project over others. Yet its benefit, of course, is that the exhibition allows sustained viewer engagement with the work. Some pieces emphasise formal or material exploration of the migration theme, whilst others foreground interpersonal interactions, giving the visitor different views on or ways into the topic. Taken together the exhibited pieces have a rich symbolism that evidences the role art can play in raising awareness and visibility of migration.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Comments