Source: Wikimedia Commons

When I was learning to drive in 1999 my instructor would carry with him a scale model of his red Vauxhall Corsa’s clutch. It looked like something out of a 1980s transport museum diorama, consisting of what appeared to be two toy cymbals. Whenever I let the clutch slip, my instructor would assume control and pull the car over. Hand break on, he’d proceed to handle the model like an overeager demonstrator in a science museum, and clash the symbols. To this day I’m convinced there’s a toy orchestra under every car bonnet. Regardless of my reputation as a clutch killer, when I pulled into the Wigan test centre for the fourth time I was convinced I’d passed. Why so confident? Well, I was carrying with me a small stainless steel crucifix, this was given to each pupil during their final year in my Roman Catholic primary school. Surely this pocket sized Jesus would absolve me of my sins against clutches and grant me a pass? No. This was the day I rejected driving, Catholicism and Vauxhalls altogether.

Now, before I get grief from the Vatican or the Vauxhall owners fan club, you need to understand why driving would elicit such a powerful response if you come from a working class town like mine. I’m from Skelmersdale, or Skem as it’s affectionately known, and if you don’t have a driving licence you’re pretty much dependent on those that do. From the late 1960s onwards the Skelmersdale Development Corporation transformed this stone and slate town once dependent on agriculture and mining, into a new town of steel and concrete dependent on manufacturing and the motorcar. Even though Skem’s population grew exponentially, with many working class families like mine relocating from inner city Liverpool, the town’s railway line lost during the Beeching Axe was never reinstated. Instead, Skem would be served by motorways, roads and plenty of roundabouts.

You’re probably asking yourself why I’m banging on about driving when this is supposed to be an article about working class communities and museums, I’m getting to that. You see, if you’re a Skemmer, your exposure to museums is dependent on your ability to reach them. It must’ve slipped the minds of the town’s 20th century utopian developers, they built an excellent library but no museum. I guess they assumed that Skemmers would hop in their cars and dart down the motorway to the nearest city centre, in our case Liverpool, for all their museumy needs. You could also make this journey without a car, but it generally involved catching a bus to Ormskirk and the train from there to Liverpool, and repeat this on return. Once there, you could marvel at oil paintings, classical sculptures, but not the history of our town. It appeared as if arts, culture and heritage took place in metropolitan museums but not in new town neighbourhoods.

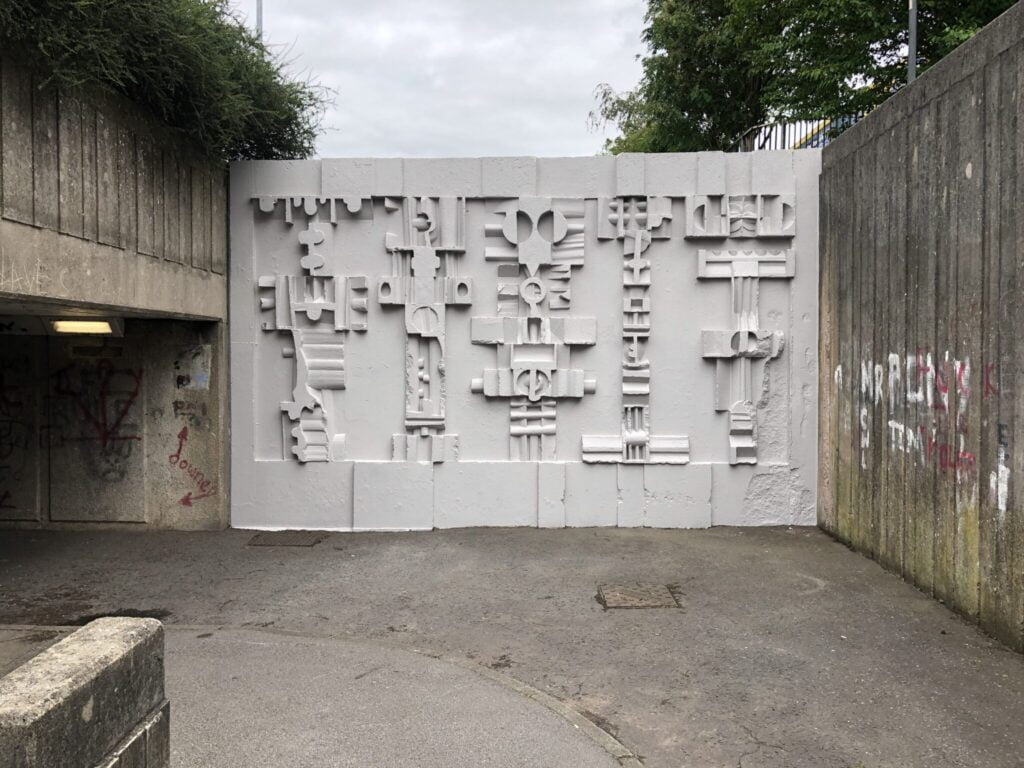

It shouldn’t come as any surprise then that when I told the careers advisor at the age of 16 that I wanted to be an archaeologist, he was about as convinced as my driving test examiners would be. I’d become fascinated with archaeology as a result of visiting innumerable historic sites during our family trailer tent summer holidays to Wales and Cornwall, combined with the odd weekend jaunt to Liverpool’s museums, and of course plenty of Time Team. Unbeknown to me at this point, my own hometown was equally as inspirational with a history and heritage stretching back to medieval times. It was only a couple of years later whilst studying A-level medieval history at sixth form college in the neighbouring town of Orrell, that it was revealed to me that Skem was listed in the Doomsday Book and the town’s name was Old Norse in origin. Suddenly The Viking pub made more sense. And it was only a couple of years ago that I discovered, courtesy of the Glassball project ILLUME, that from 1966-1976 Skem had a resident artist, Mike Cumiskey. You can find Cumiskey’s brutalist concrete reliefs lining the walls of the Railway Road subway, or subbies as we call them.

NEW TOWN RECLAMATION : Skelmersdale. This is one of Mike Cumiskey’s concrete wall reliefs, it was reclaimed by artist André Stitt, artists from Glasball and local residents in 2018 as part of the ILLUME project. Image courtesy of Glassball.

You’d be forgiven for believing this article is about what working class towns like Skem lack, but you’d be wrong. Skem may not have a museum but that doesn’t mean it’s devoid of arts, culture and heritage, far from it. Then there’s the townspeople themselves, Skemmers have character, creativity and curiosity in abundance, enough to fill the biggest museum several times over. This is reflected in projects like ILLUME and Skem, I Love You, and the work of the Skelmersdale Heritage Society. However, the notion that inner city museums are the epicentre of arts, culture and heritage, and should draw in working class communities from beyond their postcode, is an ingrained and persuasive one. As the UK emerges from lockdown there needs to be a serious revision of the dominance of the motorcar, metropolitanism and museums in determining which arts, culture and heritage is valued and how it’s accessed. The solution isn’t building more local museums, but it’s about ensuring museums redeploy their resources to support place making and doorstep arts, culture and heritage.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: access, arts, Car, Culture, driving, Heritage, history, metropolitanism, motorcar, museum, railway, Skelmersdale

Comments