2020 is a good year for anniversaries. Wordsworth, Beethoven and Hölderlin were all born 250 years ago. I’ve been occupied with the last of those – born 20 March 1770 – as a student, critic, translator for most of my life, and was invited to a celebratory conference in Berlin, to join other translators of his poems in readings and discussion of their work and of his reception in their languages. The countries to be represented were Italy, Spain, Sweden, China, Portugal, Turkey, Estonia, Lithuania, Iran, Hungary, Greece, South Korea, Argentina and the United Kingdom. Will it ever be possible now to read such a list without thinking of COVID-19?

By the end of February I was getting anxious about attending. I rather despised myself for that. And as I worried and hesitated, the idea I’d had for a radio play two years ago came back to me very persuasively as a long story. It would concern the poet Friedrich Hölderlin, his lover Susette Gontard (the wife of a Frankfurt banker), and a wild young man by the name of Wilhelm Waiblinger who befriended Hölderlin in 1822 and wrote the first intelligent and sympathetic account of his madness. Susette Gontard died of TB (after nursing her four children through scarlet fever) in 1802, she was 33; Waiblinger died of TB in Rome in 1830, aged 25, and is buried with Keats and Shelley in the Protestant Cemetery there.

These three persons took possession of my thinking, they were my last thought at night and my first every early morning. And in the beginning at least, they haunted me like voices of conscience. I ought to go to Berlin, after Brexit every such gathering to speak of poetry and translation is an act against my native land’s decided insularity, I must be there. The first coronavirus death in the UK was announced 5 March. I began writing on the 6th; sent my apologies to the good people in Berlin on the 9th and had the kindest note in reply: the celebration was postponed till September, when things would surely be back to normal. Thus comforted, I worked at my fiction every day, and finished it (but for revision) yesterday. The death-count overtook my word-count.

Like many back then, Hölderlin and Waiblinger were great walkers. As a student neglecting his studies (theology), Waiblinger walked over the Alps to Milan and back. In my story I invented several more such treks for him, confident his ghost would thank me. Hölderlin walked all or most of the way to each new employment as a house-tutor, the farthest, in winter, to Bordeaux. When I began my D. Phil. on him, I did the first stretch of that journey, from Tübingen as far as Strasbourg, through the snowy Black Forest. There and elsewhere I retraced his steps. For my story, I looked at my notebooks of 1968-9, went over the routes on the maps. So in lockdown, confined as vulnerable, I walked hundreds of miles in all weathers through Germany, Switzerland and France, on behalf of two poets, one who would die young, the other who would die old, mad, and in the absence of the love of his life.

In 1932 Edward Thomas’s widow, Helen, visited the poet and composer Ivor Gurney in Dartford lunatic asylum. Gurney had never met Thomas but had set 18 of his poems. She was appalled by Gurney’s circumstances and on her next visits brought her dead husband’s OS maps with her, sat on the cell-bed with Gurney and watched him trace with his finger walks he knew and missed through his native Gloucestershire. She saw him freed for a while, moving on beloved tracks with his fingertip.

Exactly twelve months ago, after weeks of obsessive planning, I set off on foot from this house in Oxford up the Thames to its source, to the Severn, the Wye, the Usk and by canal towpaths and pathless streams and mountain tracks got myself in eleven days, sleeping out six of the nights, to the house our daughter and her family live in, south of Aberystwyth, with a view of the western sea.

God bless the BBC! In lockdown they gave me and nine other writers fourteen minutes to imagine or remember an elsewhere strong enough to help. I recalled and collected, as I do when I can’t sleep, some of the countless streams and rivers I have climbed to lakes among encircling hills and sleeping out there and swimming there, and making across the watershed next morning very early and quite alone to a stream that would be my clue back down. A lifetime of that, a benign corpus of strands and glimpses, surfacing like stray lines of verse on the borderlands of sleep, clear, and vaguely haloed around with a lost context.

Hölderlin and Susette Gontard loved in a time of revolution and war. When the French bombarded Frankfurt in 1796, Gontard sent his family and their house-tutor Hölderlin away to safety in Westphalia. On that journey, which sealed their illicit love, the roads were crowded with refugees. Hölderlin’s solitary walking took him two or three times through vacated battlefields. Of their generation Wordsworth said, “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive”; but for the next generation in broad daylight came the restoration of the old order. In 1945, Britain, though certainly not bliss, was at least hopeful. Since 1979 it hasn’t been that, and where we are now, who knows?

None of the writing and remembering and thinking I’ve done in lockdown has been an attempt to escape from the fact of pandemic sickness and dying. Naturally in confinement I’ve wanted freedom. And found it in making a fiction of real people’s lives and revelling in much remembered and invented long-distance walking. But that is not a denying of the facts. It is an answering back: ‘Yes, these are the present circumstances, but …’ Memory and imagination are the writer’s comrades in resistance to despair.

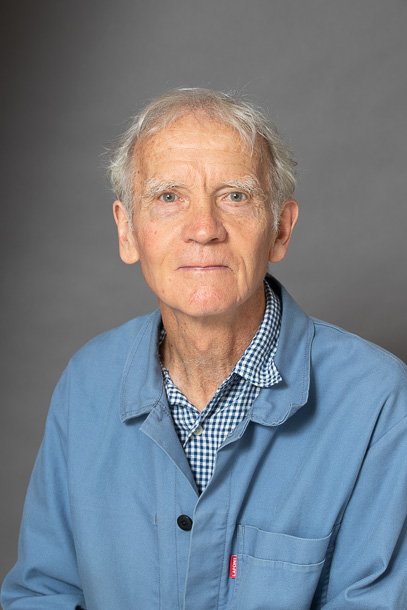

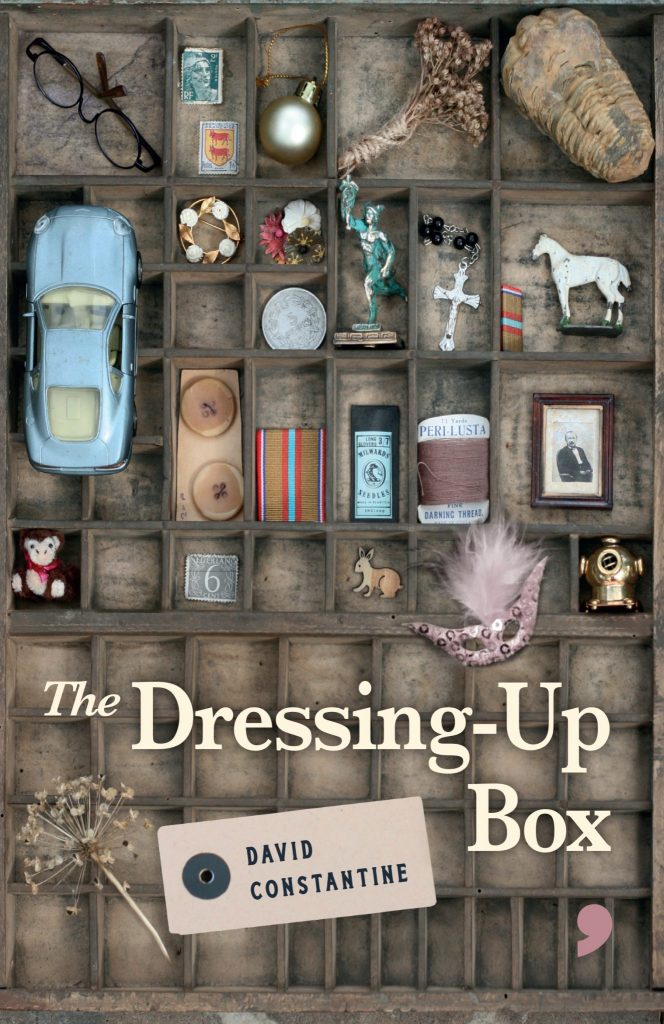

David Constantine’s new short story collection ‘The Dressing-Up Box’ is published in paperback on the 25th June by Comma Press. Pre-order here: https://commapress.co.uk/books/the-dressing-up-box-1.

Comments