In August, Comma Press will publish a new collection of short fiction by much-lauded science fiction author, M John Harrison – ‘Settling the World: Selected Stories 1969-2019’.

M. John Harrison’s stories traverse the spaces between genres – horror and science fiction, fantasy and travel writing. Here, in a landmark collection of his finest short fiction from 50 years of writing, we see the master of the New Wave present extraordinarily strange, surreal and poignant tales. Harrison is truly a writer in a league of his own and the handpicked stories in this collection showcase his most interesting, eerie and exhilarating stories to date. Comma Press asked M. John some questions about the new collection and his life’s work so far.

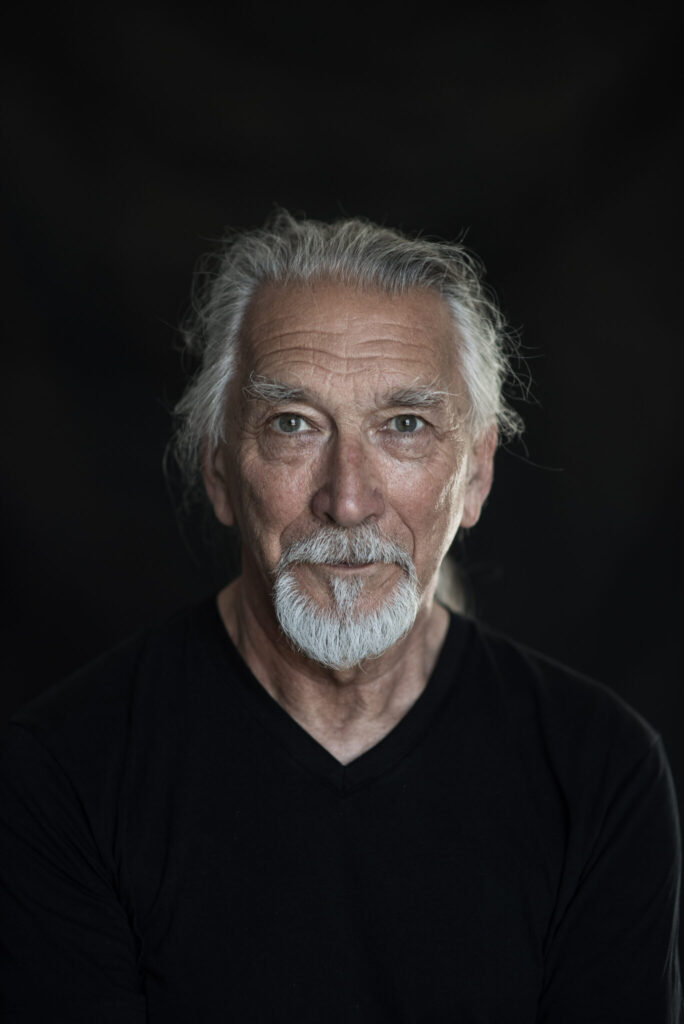

Credit: Hugo Glendinning

‘Settling the World’ is a collection that looks back over the last 50 years of your short form writing. Reading through your archive, was there anything about the way your work has evolved that surprised you?

The older stories are clunkier than I remembered and very much of their time. On re-reading, ‘The Causeway’ came across as the most modern. A little bit of cleaning up and I could have written it last year: that was a surprise. Otherwise, nothing much. I can see changes in technique from 1976 to 1985; again in the mid-to-late 90s; and finally quite recently, with the onset of late style. But the issues – loneliness, alienation under capitalism, failure of romance, explanatory collapse of the major characters – remain pretty much the same.

As well as your short stories, you’ve written twelve novels over the course of your career so far, including your latest release ‘The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again’. What does long form writing enable you to explore that short form does not? Or rather, what do you bring differently to each medium?

You can be more focussed in a short story, in fact, you have to be. At the same time, you have to learn how to produce a fluid surface. In both short and long form I make images and enchain them like dance steps, to add a sense of flow-through and change which I hope replaces the traditional structures of “story”. You have to be careful with that at the length of a novel. But as long as you keep control of the masses, rhythms and the overall structure, you can go to town on it between 50 words and 3,000.

Which writers and artists have been the greatest inspiration to you throughout your career?

I honestly couldn’t say. Short answer: a lot. In 50 years you read a lot of writing, look at a lot of art. After 50 years, your newest “inspiration” is instantly modified by the ghosts of all the earlier ones. Meanwhile, the you that you built from all of that reading and experience is quietly repurposing a new version of itself for every new piece of work. It’s a process you perceive as an identity, an uber-ghost among ghosts, your inherent voice. It lives somewhere down inside you. It knows when to change and when not to. It always knows more than you do. Since the mid 90s, I’m often quite scared to be sharing space with it. When it comes on-stream – sometimes a bit brusquely, a bit contemptuously – it elbows me out of the way and whatever I’m writing begins to take the proper shape.

You are known for traversing genres in your work which lies in the cracks between science fiction, horror, fantasy and travel writing. These categories aside, how would you best describe your own writing?

The earlier stories were insistent. They were determined to make themselves heard. Now, they tend to be wry and amused – you can read them, but they don’t mind if you don’t. They were always too much themselves to be passed off as “genre-adjacent”. I use whatever mix of genres I need to service the themes and meanings. Genre looks at itself as its own produce – if you write generic science fiction, then the science fiction is the be-all and end-all of the text. It’s like a substance the writer is supposed to extrude. That’s the main problem with that. In my stuff, the genre is not the product, it’s there to serve the product. It’s taken up and put down when the product demands. If you read for the genre element, you’ll be missing what’s actually there and conclude there’s no content. They’re often quite emotional stories: but a refusal to over-cue emotional states has led to some mistaken opinions about what I do and how. In terms of tone and presentation, I’d like people to feel as if I were reading the stories aloud to them. I love reading aloud and the extra dimension it adds.

By rewriting the ordinary world from the strange angles that you take, what is it that you are asking of your readers? Do you have a particular aim when putting your writing out into the public sphere?

Like most writers I’m trying to illuminate the ordinary, but at the same time to use the ordinary to illuminate the strange. Also to ask: why do we always assume that the act of fantasy is the light source? What qualities of the act of fantasy (acts of fantasy now comprising the entire underlying ideology and aesthetic of our era and thus being an appropriate subject for fiction) might you use the light of the ordinary to examine?

Landscape is hugely important in your stories, whether its city streets or rolling hills, and this seems at times to exaggerate the solitude of your characters as well as the huge scope of their internal lives. How has your own relationship with the landscape informed this?

Fully. I have only my own relations with the landscape to work from. That side of the writing is as experientially-based as I can make it. I try to leave the house as a blank slate, knowing nothing about the world – oh, what is this little flower, with its yellow heart and white petals? Of course, that’s not possible. There are other issues, obviously. What a priori cultural elements do we use to build internal landscapes out of outer ones? (Or indeed to turn landscapes into home extensions and outdoor gyms?) And I’ve always been fascinated by the way a landscape draws you in only to change around you as you use it, so that you can never enter a view. Finally, a landscape is always defined by the way you use it, yet vibrates constantly with all the other uses that are being made of it, or have been made of it. For me, my novel ‘Climbers’ wasn’t about a landscape, it was about a relationship with a landscape. These stories are, too.

What is your favourite story in the collection and why?

‘Doe Lea’ and ‘Yummie’ are my favourites, because they have that wryness to them. They seem to use the technique you mentioned—rewriting the ordinary from a strange angle, and its important complement, writing the strange from an ordinary angle—in a subtler way than before, allowing the emotional subject matter more space (although I hope that remains under-cued, leaving plenty of space for readerly input). I still have a sneaking regard for the grotesque comedy of ‘I Did It’, the shortest story in the book, which was also the one that taught me how to do a light, fluent surface.

M. John Harrison is the author of twelve novels (including In Viriconium, The Course of the Heart and Light), as well as four previous short story collections, two graphic novels, and collaborations with Jane Johnson, writing as Gabriel King. He won the Boardman Tasker Award for Climbers (1989), the James Tiptree Jr Award for Light (2002) and the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Nova Swing (2007).

Settling the World: Selected Stories 1969-2019 is published 20th August and available to pre-order now.

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: book, Comma Press, fantasy, genre, horror, interview, launch, light, M John Harrison, publication, publisher, science fiction, Settling the World, short story, story, writer, writing

Comments