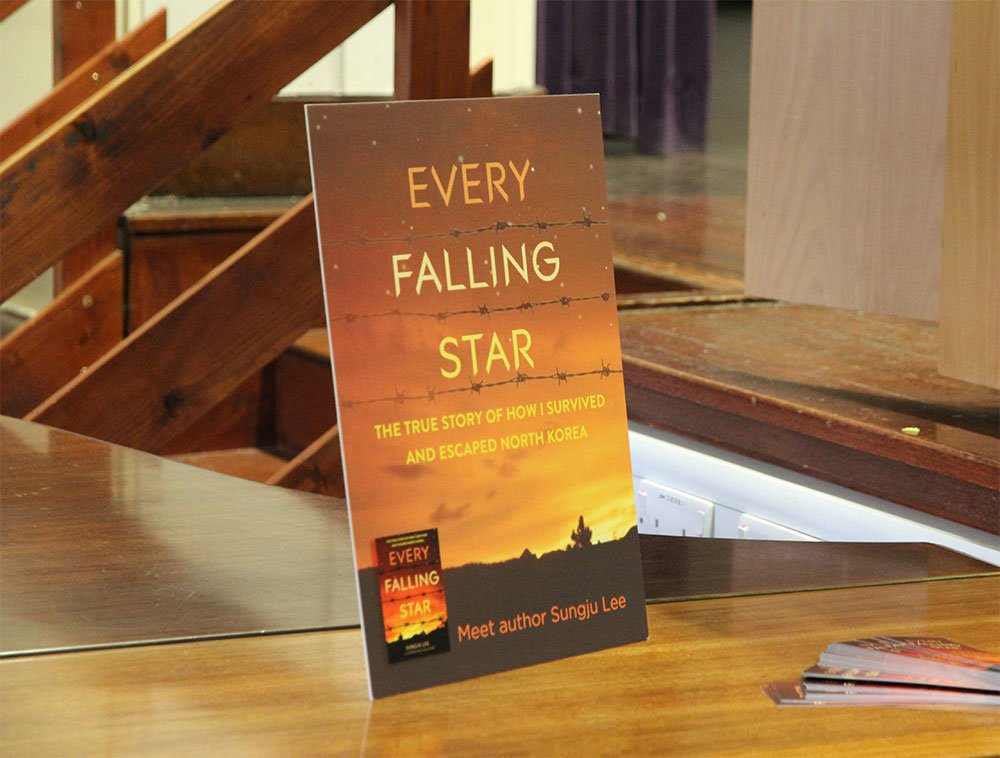

As I’m sat in the audience at Manchester’s Central Library watching Sungju Lee talk about his memoir, Every Falling Star, it’s more than a little hard to believe that the happy, sprucely dressed chap standing before me was once the very same kid from his stories, left to fend for himself as a teenager on the streets of North Korea. He radiates geniality, speaking softly and cracking jokes, while gradually telling us the tale which led to the nightmarish existence he lived for five years as a North Korean street orphan (kotjebi).

He gives his talk in presentation format, beginning by giving the audience an idea of the economic and social divides which are present between the North Korean capital of Pyeonyang and the rest of the country—basically “like Hunger Games, but in the 21st Century”, he explains. He flicks through slides which demonstrate this disparity: Pyeonyang isn’t too different to the modernised cities familiar to those in the West, well-maintained urban centres with buildings, schools, transport, and green public spaces. The rest of the country he describes as more like a barren wasteland, where amenities are scarce, and poverty and malnutrition are the norm.

Lee has been one of the few people to experience life on both sides of this polarity. Fortunate enough to spend his first years in Pyeongyang, his earlier memories are of his family’s relative affluence, one of his pasttimes being a game affectionately known as ‘Wipe Out USA on Earth’. This luck was not to last, however, as the family saw themselves expelled to Kyongseong in the north-east of the country, his father having been accused of criticising the government.

Lee’s memoir is the first of its kind to target teenagers as its audience, and his story certainly takes enough gruesome and heart-wrenchingly serendipitous twists and turns to rival even the most wildly imagined young adult fiction. From the loss of his parents, who traveled to China in search of food, never to return, to fending off malnutrition by eating insects, begging and stealing, and onto being forced to bury some of his closest friends, Lee has been through the unimaginable—ten times over. But in a providential encounter, a seemingly clairvoyant man reminds Lee of his forgotten name, discarded long ago when he took to the streets and adopted the name Chan. After attempting to rob the man, it finally dawns on Lee that this man is, in fact, his grandfather. Lee moves into his grandparents’ home, entrusted with care of the livestock.

As if that wasn’t all wild enough, he also manages to escape North Korea. Curiously, he doesn’t go into much detail about the escape itself, instead focusing on the new life he was plunged into, which brought its own challenges and surprises. Watching a TV drama for the first time, he describes how an on-screen smooch was “[his] first sexual education”. He gestures towards a projected image of a yellow chick in a sea of black ones, describing his feelings of isolation and inferiority as a lonely North Korean in the south. He recalls spending two hours choosing a pen, afterwards musing “This must be freedom. I found freedom at the stationery shop”.

Lee maintains that his memoir has no political agenda. This is true in a sense—the book is, first and foremost, simply a great story. However, as well as the story being in itself powerful, the very act of telling stories in and about a place in which communications and freedom of speech are so limited is, I would argue, necessarily political. And he goes on to recognise the political significance of these stories, expressing a conviction that sharing stories such as his is an essential part of working towards unification of the North and South. He ties this into the media context, criticising Western media’s readiness to sensationalise and fetishise its criticism of the regime, rather than utilise the presence of thousands of defectors to humanise coverage of North Korea. He sees this as symptomatic of a wider issue, whereby the West’s approach of “strategic patience” with regards to the country in practice signifies the absence of policy, and therefore a refusal to proactively work to combat human rights abuses on the part of the North Korean government. According to Lee, rather than make Western countries complicit in these human rights violations, diplomacy and trading with North Korea would, in fact, give countries such as the UK and US some kind of leverage to begin to influence the lives of the North Korean population and to nudge the country to open itself once more to the rest of the world.

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: author event, autobiography, Central Library, defector, escape North Korea, Every Falling Star, Korean author, life in North Korea, Manchester Literature Festival, McrLitFest, MLF16, North Korea, Sungju Lee

Comments