(Of good and evil) … “And every time they meet the same thing has to happen;

It is Evil that is helpless like a lover

And has to pick a quarrel and succeeds

And both are openly destroyed before our eyes.”

– W. H. Auden

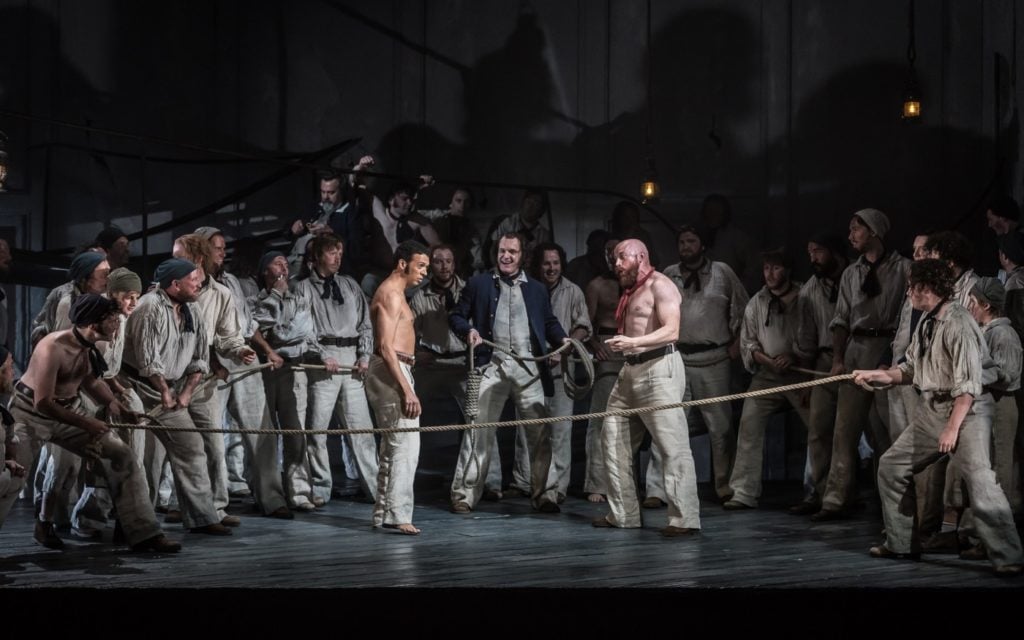

The uncharacteristic and frustrated punch from the beauteous, goodly Billy Budd that floors and kills the petty, sadistic tyrant Claggart is the pivotal moment to the whole of Britten’s opera and the Melville novella from which it was sourced. Every action before it, be it to contextualise the claustrophobic conditions and pitiless regime on board a British man o’ war fighting Napoleon or portray a timeless infatuation with and destruction of unsuspecting innocence by a scheming corruption, leads inexorably to Billy’s outburst. Similarly, all that follows, the invocation of the Mutiny Act, Articles of War and King’s Regulations upon which Billy Budd, despite our and the crew’s sympathies, is condemned and hanged, stems from that fatal blow.

Melville the author, Forster and Crozier the librettists and Britten the composer never intended it to be a comical incident, but that is what it became on the opening night. No-one expected Alastair Miles’ (Claggart’s) nose to issue real blood, but contact with Roderick Williams’ (Budd’s) fist should have been more realistic. Perhaps, it had been too good in rehearsal …

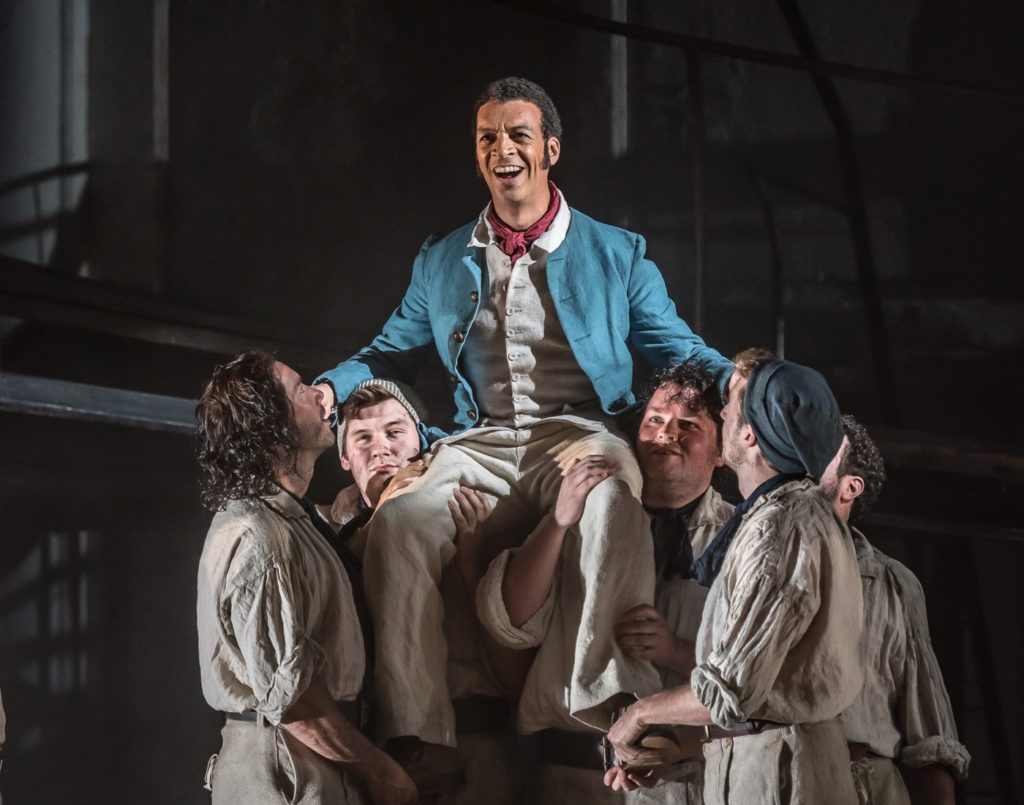

This aside, the evening was musically wondrous. Williams’ voice showed all the acutely beautiful responsiveness to the sound and meaning of words, even though some of Britten’s writing is heat-of-the-moment declamation. I hope it does not stymie a burgeoning career, but, with this performance and his recent recordings of the art songs of Finzi, Howells and Gurney, I would like to suggest that English music, evidently, has found a compelling new vocal champion. Similarly, conductor Garry Walker – I have heard his impressive Elgar – kept the orchestra lithe and alert to the many nuances of Britten’s score, which surely marks him out as the natural successor to the likes of Vernon Handley and Richard Hickox.

Miles’ Claggart held the audience’s attention in his portrayal of secretive malevolence, about which only we knew yet could do nothing. As to whether his infatuation is sexual in origin remained agonisingly inconclusive. Alan Oke’s Captain Vere, all regret and self-questioning in his dotage, but helplessly duty-bound at Budd’s trial, was the epitome of doubt and remorse. Britten, perhaps, found Vere the more interesting figure in that there is ample room for character development and his impotence in trying to have Budd spared comes across as an aching human failing.

Elsewhere, there is fine vocal support from Peter Savidge (Mr. Redburn), Adrian Clarke (Mr. Flint) and Callum Thorpe (Lieutenant Ratcliffe). The men of Opera North’s chorus sprang gloriously into life for their working songs and collective outrage.

Sung in English without surtitles. See here for dates.

Filed under: Theatre & Dance

Tagged with: Benjamin Britten, Billy Budd, leeds grand theatre, opera north, Tom Tollett

Comments