(c) Rob Battersby

This winter FACT Liverpool premiered ‘Broken Symmetries’, an exhibition resulting from a collaboration between the gallery and CERN laboratories’ growing arts programme.

It’s a brave feat to take some of the most challenging scientific theories and investigations in modern day physics and throw visual arts into the mix. The hesitant symbiosis between arts and sciences is now very much established and the benefits to both disciplines brought about by collaboration are common knowledge. Personally, I am an advocate for all multidisciplinary openness and a firm believer in looking for inspiration outside of your own circles. But despite great intentions, ‘Broken Symmetries’ is a show that communicates very little, and because of that it provides the perfect chance to comment critically on the development of FACT’s artistic programme.

I have written about FACT before and each time I try to focus on the positives. There are always curatorial touches that give me a brief feeling of satisfaction or a little ‘aha!’ moment. But there are only so many times a writer can do that before they start sounding like a broken record if there are other more interesting aspects lurking beneath the glossy praise.

The truth is that not much changes or evolves, except for the gallery layout.

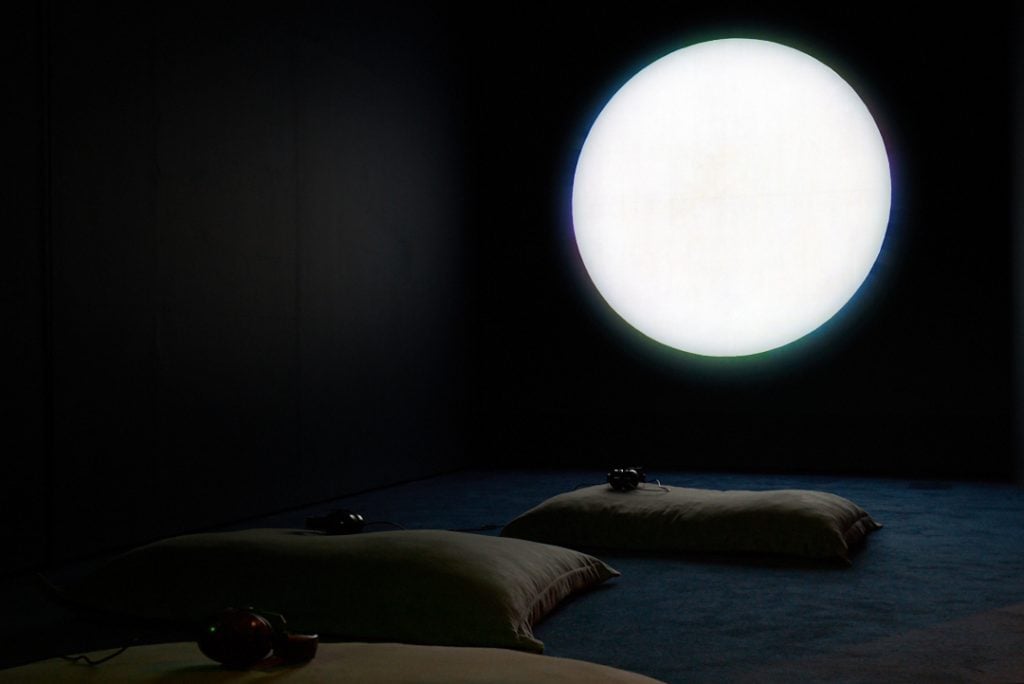

When going to see an art exhibition at the Foundation of Arts and Creative Technology, it’s fair to expect a show that requires absolute attention and time, and ‘Broken Symmetries’ is no different. Each piece greedily invites us in for a closer look, but the proximity and time we allow them don’t provide much in return.

The scientific concepts offered by the artworks on display can be captivating, but sometimes viewing them through the lens of art is no more interesting than learning directly about the concept itself. In fact it adds another layer of complexity to already complicated ideas. While it is possible to percolate scientific knowledge through the filter of art, it must be done skilfully and sensitively, otherwise key information and, most importantly, comprehension gets lost along the way. The artists forcibly viewing what they have learned through the lens of their existing practice run a risk of clouding the initial ideas that inspired them. Aestheticising scientific concepts does not always add anything new or make them easier to understand.

For this reason the most interesting artworks in the show are those that provide the scientists involved with a direct voice or convince them to see their own work from a fresh perspective. A new platform for expression reveals scientific voices that sound more human than when they’re edited down to academic papers and equations, but still entirely informed by their work. The humane truths expressed as a result of it often are chillingly accurate and that is perhaps what makes the science behind them even more exciting.

Let’s take a look at some of these. Semiconductor’s film ‘The View from Nowhere’ (2018) offers close observation of the CERN laboratory and its inhabitants, where interviews with scientists act as narration for the very well produced video. The wisdom present in their answers (‘You have to think in a creative way but with logical rigour’) is matched by the romantic perspective from which the camera captures their surroundings. Satisfying geometry and classical compositions are found in unexpected places, revealing the beauty of the usually dreary office spaces and noisy machinery. If you tried to imagine how an artist would view a physics lab, it would most likely look like Semiconductor’s piece. The result is even better because it’s asking the right questions of fascinating people.

(c) Rob Battersby

Suzanne Treister’s ‘The Holographic Universe Theory of Art History (THUTOAH) (2018) investigates the theory that the universe exists as an intricate hologram. This multimedia work consists of a video comprising 25,000 images of art historical works starting with cave paintings up to the present day, shown chronologically and at the headache-inducing speed of 25 images per second. It is played against an audio recording of interviews with CERN scientists whose conversation focuses on the holographic universe principle. Triester draws parallels between scientific discovery in the field and art historical signifiers that suggest the theory has been present in artworks since the first people admired their paintings on cave walls, led by an unconscious intuitive hunch.

Alongside the video, Treister shows a series of watercolours created by the scientists at CERN, attempting to translate theory into visuals. The watercolours range from shy, pastel-coloured diagrams to Treister’s own bold, refined pieces with visual hints of mysticism and, weirdly, Russian Constructivist-style posters.

(c) Rob Battersby

While the video is fascinating, the flashing images mean it can only be enjoyed for a few minutes at a time, and the interview narration is at times difficult to follow. But this is not a simple concept, so grasping it should not come easily. ‘THUTOAH’ does not claim to make expert use of the science that inspired it. What it does very well, however, is make that science visible to a new audience that is better acquainted with an art gallery than a physics lab. It isn’t a humble piece that bows before the pillars of science, but one that approaches the subject from a playful and mystical viewpoint, without disregarding the expertise from which it stems.

Many of the other artists in the show choose sensory overload as their key medium. The inclusion of works involving multiple senses is valuable and increasingly used in exhibits, thanks to the slow overwriting of old-fashioned museum rules like ‘Do not touch’. But while one loud installation or flashing video can be a memorable experience in the right environment, here it feels like the sheer amount of stimuli was not considered while planning the visitor experience. It’s just all too much.

Where does the recent trend for oppressive, exhausting-to-be-around artwork come from? If the aim of a work is to engage multiple senses and loud noise is the appropriate way to do it, so be it. But after the third piece in a row where all you get are visual cliches paired with deafening sounds you’ll leave with a headache and not much desire to think about it ever again. Unfortunately this is a large oversight of the curation. Works that could potentially be interesting in a different setting become unbearable when densely populating a limited space.

Physics aside, at some point we have to question why the FACT galleries look and feel the same with each new exhibition. Do visitor numbers stay high enough to repeatedly keep doing the same thing? Is feedback continuously positive or do visitors feel out of their depth and unable to speak up? There are feedback forms waiting to be filled in at every corner, so either there are no complaints or FACT isn’t listening.

Sure enough it looks impressive. Given the gallery’s penchant for interactivity it might even look accessible. But it seems there is a group delusion stemming from the comfort of using new media that, in theory, automatically results in innovation and cutting edge results. The recent shows lack freshness and don’t achieve the promised, enormous task of challenging the viewer’s notion of reality. Visitor experience gets lost in the incessant flow of noise and International Art English.

Pairing giants of science with artistic minds should result in more accessible outcomes than noise and random arrangements of objects. Curatorially, being considerate of the viewer’s experience never leads to a bad experience, and this show disregards the visitor’s senses and limited patience. While a collaboration with CERN is a cool prospect, the conversations resulting from it got lost in the artists’ overcomplicated visions. For such an exciting collaboration, ‘Broken Symmetries’ was a wasted opportunity.

‘Broken Symmetries’ at FACT has now finished and will later be shown at CCCB, Barcelona; iMAL, Brussels; and le lieu unique, Nantes.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: art, cern, experiments, FACT, film, liverpool, painting, physics, Science, technology, video, watercolour

Comments