While the Weimar Republic refers to a post-war age in Germany, the era is not without its conflict. As the guns of the First World War fell silent, a new upheaval lay before the nation. The trenches were left behind, replaced by the new battle ground for a deadly socio-political war: the everyday household, farmer’s fields, and beerhalls. Tate Liverpool’s current two-part exhibition Portraying A Nation: Germany 1919-1933 (until 15th October) centres on the embroiling conflict of the doomed Weimar Republic.

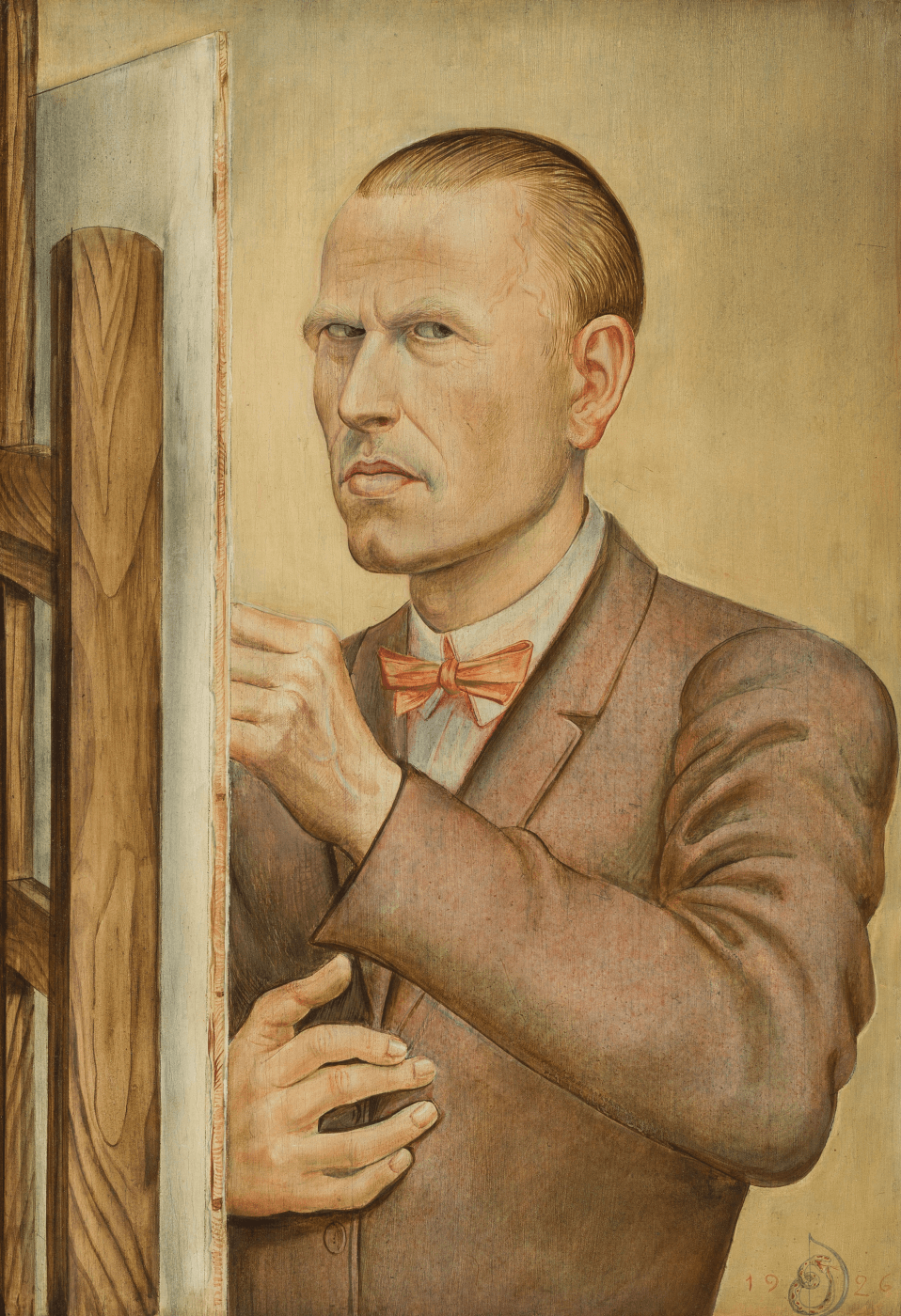

Featuring the works of photographer August Sander and artist Otto Dix, the exhibition follows the timeline of two contrasting art practices. The first focusses on Sander’s pristine portraiture photography, which elegantly captures an age of deteriorating hope through 144 monochrome images. The second comprises of Dix’s Dadaist depictions of the First World War, and the decadence that followed. Calm and collected sits beside horror and hedonism, but not without flashes of sentiment – such as Dix’s biblical picture book designed for his Granddaughter, Hana.

Germany’s democratic aspirations, brought about through an allied victory in 1918, is best represented by Sander. All too often history paints the people of a warring nation with the same brush as those orchestrating the battlefield. Sander dispels such a belief, sharply zeroing in on the faces of those who wished to build a new Germany from the ruins Wilhelm II’s failed European conquest.

Although many of the photographs taken from 1919-1922 capture welfare, widows and gross hyperinflation, there is an underlying stability that radiates from each stern look and occasional cracked smile. Political unrest may have been ensuing, but that did not stop the German people from paving the way for what was to be known as The Golden 20s – a bust to boom rollercoaster ride that brought art, music and theatre to cities across Germany throughout the decade. An endearing honesty is carved into the sharp features of each and every subject in Sander’s photographs. The images are time stamped and sincere – a true product of an aspiring social environment. The foul dip of the Weimar rollercoaster is not yet in sight.

Sander was determined to photograph every face in Germany; the farmer; the skilled tradesman; the woman; classes and professions; the city; the last people – all of whom were to be exhibited in his grand project ‘People Of The 20th Century’. However, due to the economic downturn of 1929 and Mein Kampf no longer behind bars, Sander’s project would remain incomplete. As The Golden 20s end, so does the optimism. Faces of ‘The Persecuted’ and ‘Political Prisoners’ begin to seep their way into the photographs.

Rather than achieve his original goal, Sander instead leaves behind an extensive documentation of a socially volatile Germany. Away from beer hall putsches and communist uprisings, the immaculate sharpness of his camera – achieved through long exposure times – captures The Elegant Woman (with her low waist dress and contemporary haircut), the plight of the sick, the blind, ‘gypsies’ and those who would be eradicated when the Nazis come to rule. Each character is integral to Sander’s aspiring Germany. While the exhibition has a handwritten timeline, which injects between the chronological photographs with details of political unrest, the eyes of each subject carry a timeline of their own. One that mirrors the Weimar’s social failings, but remains determined to reach a future beyond reparations and the war. A determination for change that inevitably brought about a more devilish rule than before.

Having served as a machine gunner in the frontlines of the German forces, it’s no surprise Otto Dix sees through the veneer of the Weimar. The parallel timelines of Sander and Dix couldn’t be further apart – except when the two briefly cross through a Sander taken portrait of Dix and his wife, Martha.

Whereas Sander looked to capture hope by way of conformity, Dix’s art revels in an unhinged smattering of battlefield memories and decadent human form. From the sassy hourglass figure of jeweller Karl Krall to imaginings of erotic brothel scenes, Dix digs beyond the regimented classes of The Farmer, The City and The Woman, forcibly asking his viewer to look beneath the conservative caricatures of the Weimar. We see a Germany unequivocally still human, and looking to forget. Acts of alcohol-infused sordidness are a proven way to forget one’s immediate troubles. Dix is well aware.

Much of the population will have optimistically expected the newly democratic Germany to recover from the war. Paying back its debts was just going to be part of the process. However, with hyperinflation and the Wall Street Crash of 1929, it was apparent that economic recovery was fanciful. Germany had lost the war and was set up to lose financially for the foreseeable future. The collection of rosy cheeks and scarlet lipstick featured in Dix’s paintings transcend the crushing asphyxiation of the Treaty Of Versailles. With visions of the trenches still fresh in the memory it’s easy to see why Dix does not fixate on the gasping economy. Experience has outweighed the intangible.

In 1924 Dix’s CV read: “I merely add that I am neither political nor tendentious nor pacifistic nor moralising nor anything else.” Such desensitisation can be found brewing in a series of 70 haunting etchings titled Der Kreig (The War), exhibited in the same year across 15 cities – although without a the controversial and unsettling ‘Soldier And Nun’. The etchings are filled with black landscapes littered with skulls and craters akin to those on the moon. A gentle hint toward the otherworldly scenes of horror that were lived and breathed by those on both sides in the war.

Portraying A Nation encapsulates a culture rich Weimar Germany that would forever be in the shadow of two aggressive regimes. The exhibition is informative, but not without flashes of character oozing from every wall. Where Sander offers a historical recap, Dix looks to distort our preconceptions in the hope we see beyond the Weimar’s cosmetic conformity. The adjacent exhibitions stare intently at one another in intrigue, creating a visceral combination that offers a bold depiction of the Weimar Republic – one that is often left untouched in the classroom.

Hindsight suggests that the Weimar was a doomed era. However, the brilliant array of contrasting art displayed in Tate Liverpool shows it was more than a benign Republic waiting to implode. Between the textured layers of the Weimar’s social structure and neurotic psyche, together, both artists provide a contorting timeline that the Nazis would ultimately try to rewrite.

Portraying a Nations: Germany 1919-1933 continues at Tate Liverpool until 15 October 2017. Otto Dix: The Evil Eye is curated by Dr Susanne Meyer-Büser, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Francesco Manacorda, Artistic Director and Lauren Barnes, Assistant Curator, Tate Liverpool. ARTIST ROOMS: August Sander is curated by Francesco Manacorda, and Lauren Barnes, Assistant Curator, with the cooperation of ARTIST ROOMS and the German Historical Institute.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: August Sander, liverpool, Otto Dix, Portraying a Nation, Tate, Weimar Republic

Comments