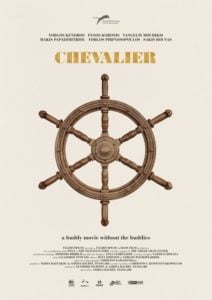

Review: Athina Rachel Tsangari’s Chevalier

July 27, 2016

A certain unease prevails in the work of Athina Rachel Tsangari which is entirely in keeping with the tone of the movement that has revitalised Greek cinema; known variously as Greek New Wave, New Greek Cinema and Greek Weird Wave. As much as the movement’s leading lights may disdain such attempts at journalistic pigeonholing, the latter designation is particularly apposite. Tsangari’s sophomore feature, Attenberg (2010), placed her at the forefront of the movement alongside Yorgos Lanthimos; whose defining statement, Dogtooth (2009), she produced – in the decade between Attenberg and her debut feature, The Slow Business of Going (2000), Tsangari developed a reputation as a producer.

Like Lanthimos, Tsangari is concerned with the intricacies of relationships between people whose inability to engage on an intimate level manifests itself in arcane games and outré coping mechanisms. The films of the Greek Weird Wave have the feel of an assault on one’s cherished sensibilities: exploring modes of pathology with pitch-black humour, taboo busting, brutal absurdism and what Tsangari describes as ‘scientific tenderness’. Where Attenberg and the short film The Capsule (2012) dealt with the strange manifestations of interpersonal discomfort from a female, personally inflected viewpoint, Tsangari has turned her attention to male gender archetypes and rituals with Chevalier.

Chevalier concerns a group of well-heeled Greek men who decide to liven up a diving excursion on the Aegean Sea with a spirited game of Chevalier. The purpose of Chevalier is to determine which of the men is ‘the best in general’. The men participate in a series of contests and appraisals designed to establish which of them is the undisputed alpha, who will leave the yacht wearing the chevalier ring which signifies their status as ‘best overall’. What follows is a figurative, and literal, penis measuring contest. Inevitably, the dimensions of the contest create an atmosphere of resentment and subterfuge, as the men hatch plots and devise stratagems that will undermined their competitors and clear their path to victory.

Chevalier concerns a group of well-heeled Greek men who decide to liven up a diving excursion on the Aegean Sea with a spirited game of Chevalier. The purpose of Chevalier is to determine which of the men is ‘the best in general’. The men participate in a series of contests and appraisals designed to establish which of them is the undisputed alpha, who will leave the yacht wearing the chevalier ring which signifies their status as ‘best overall’. What follows is a figurative, and literal, penis measuring contest. Inevitably, the dimensions of the contest create an atmosphere of resentment and subterfuge, as the men hatch plots and devise stratagems that will undermined their competitors and clear their path to victory.

Though Tsangari is loath to describe herself as a political filmmaker, one can’t escape the feeling while watching Chevalier that her film is a response to the chaos that has overtaken post-recession Greece, and the forces which precipitated this crash. Chevalier plays like a royal court intrigue drama written by David Mamet and directed by Chris Morris. We see a wealthy elite participate in deleterious games, while the servants speculate below stairs and facilitate its continuation: it is an astute study of class, power and hierarchy. Tsangari and co-writer Efthymis Filippou get under the skin of the male psyche, the frailty and uncertainty that underlies wounded macho pride in a climate of shifting expectations.

These characters could so easily have been irredeemably odious, but the quality of the writing and acting lends their hubris a tragic patina; each member of the large cast has a distinct reason for pursuing the self-validation implicit in the game. Tsangari is not a believer in back-story, preferring to afford the actors the room in which to find their characters over the course of inhabiting them. This approach lends a certain spontaneity to the performances – particularly good are Makis Papadimitriou as the bumbling Dimitris, athlete-turned-singer Sakis Rouvas as the fading pretty boy Christos and Yiorgos Kendros as the menacing and Machiavellian Doctor. Much comic mileage is drawn from the intense pedantry which prevails over the rules and regulations which govern the contest. Tsangari maintains an almost anthropological distance, using static medium shots to position the viewer as a detached, almost incredulous, observer to this ongoing game of pricks.

Chevalier rivals The Lobster (2015) in its earnest commitment to surrealism; though this is a comic piece, it never once tips its hat with the stylistic insouciance that so often renders screen comedy inert; it has the formal rigour of a filmmaker like Michael Haneke without treading on the laughs. As with so many Greek Weird Wave films, there is a steadfast refusal to make sense; for all its symbolic resonance, Tsangari would never stoop to being didactic. The film is, perversely, a more powerful statement on the cruel, ruinous logic that rules the world, and the rage felt by Greece’s dispossessed, for its wilfully awkward energy. The Greek Weird Wave sensibility seems increasingly to speak to a spreading sense of ennui and anomie, and Chevalier could well be the final major work before it goes global.

Follow Daniel Palmer on Twitter at @mrdmpalmer.

Comments