Review: Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979 @ Tate Britain

August 16, 2016

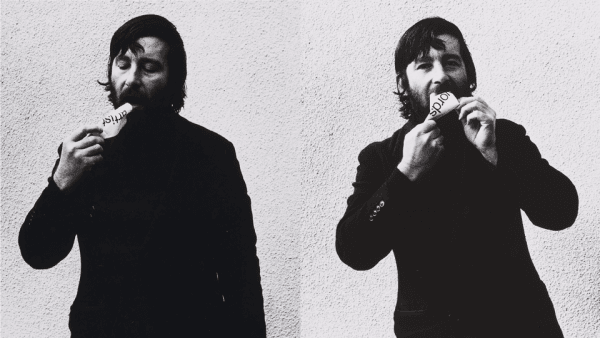

Keith Arnatt’s ‘Art as an Act of Retraction’ (detail) 1971 Tate © Keith Arnatt Estate

Conceptual art is divisive. Many people are put off by the idea of an idiosyncratic, elitist discussion among artists, critics, and prize judges to the exclusion of the average gallery-goer. This exhibition is surprising, therefore, in its swiftness to paint conceptual art as fundamentally reactive and introverted. The first room, centred on Roelf Louw’s ‘Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges)’, traces the origins of the movement to an ongoing rejection of the Modernists’ emphasis on the ‘finished’ work of art. Much of the exhibition, particularly the sections dedicated to Michael Baldwin and the Art & Language group, is more concerned with the conceptual artist as critic rather than the artist as artist. It is not unusual to make the point that every artist is to some extent a critic of their predecessors, but the exhibition highlights how the scales get skewed for artists who trade in ideas over matter.

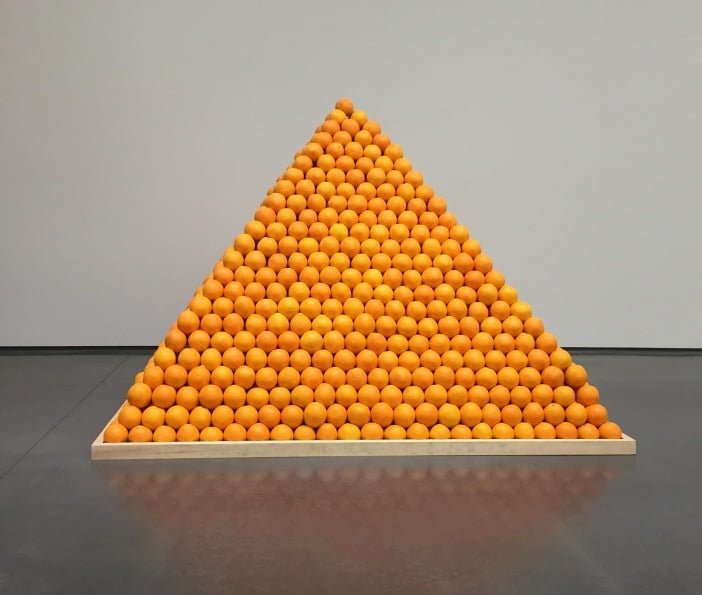

Roelf Louw’s ‘Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges)’

Where Modernist artists in general focus on individual encounters with completed works, conceptual artists shift the focus onto ongoing processes of construction and deconstruction. The exhibition thus places various types of matter in dialogue – canvas, photography, eight-tracks, oranges – engaging the viewer in resistant, disrupted or self-defeating acts of interpretation. Mel Ramsden’s ‘Secret Painting (1967-8)’, for example, features a monochrome canvas alongside a block of text, reading: ‘The content of this painting is invisible: the character and dimension of the content are to be kept permanently secret, known only to the artist.’ The interpreter is audaciously shut out of the act of interpretation, which is retained as the artist’s privilege. Except, of course, that the interpreter has plenty to play with: the monochrome paint, for instance, and Ramsden’s choices in words and presentation. The exhibition places Ramsden with Baldwin and the Art & Language collective, and Baldwin’s Untitled Painting (a mirror clipped to a canvas, 1965) hangs nearby. The appointment of the space invites us to use Baldwin’s reflective, multi-subjective surface as a means of reading the opaque singularity of Ramsden’s monochrome.

The most valuable part of the exhibition, particularly for sceptics who might prefer solid matter to ideas, is its placing of often deliberately obscure works within 20th century art history. The dates 1964-1979 run from Wilson’s Labour to Thatcher’s Conservative governments, inviting us to view the works as political and social statements as much as experiments in aesthetics. This feels flatly arbitrary, however, which is a shame, since much conceptual art deals in things which are dynamically arbitrary. It is only in the last, smallish room, which deals with the mid- to late-70s, that we see the works as responses to broader social changes rather than just to other artworks.

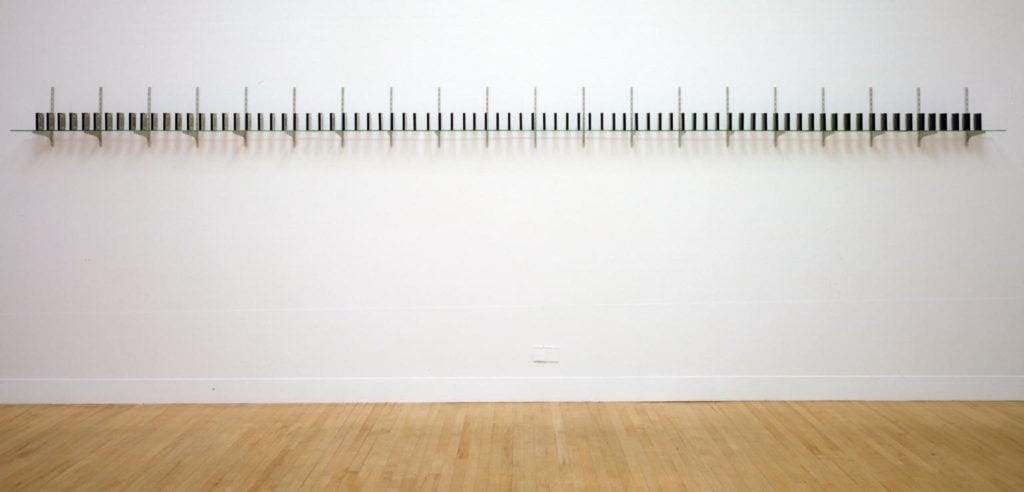

‘The Spring Recordings’, 1972. David Tremlett

I suspect the intention was to give the newcomer a stable interpretative framework to preempt the charges commonly levelled against conceptual art, but this makes the whole thing feel more like an art history textbook than a gallery. The rooms are very text-heavy, with half the space taken up by old art journals and exhibition booklets. These are interesting, but get tiresome quickly, particularly craning over display cases.

What the exhibition gains in cogency, it loses in music and vitality. The artworks become like historical artefacts, too reliant on context to come fully alive. It is tempting to chalk this up to the genre, since much conceptual art revels in its own dependencies. This wouldn’t be entirely fair, however, not least because some works – Hamish Fulton’s Hitchhiking Times from London to Andorra 9-15 April 1967 (1967) and David Tremlett’s The Spring Recordings (1972) in particular – are used to show how the idioms of conceptual art can pack considerable emotional weight. Both these pieces use sparseness of matter to communicate a vastness of personal experience, only communicable by the enormity of the space outside the works’ parameters. Their dependence on context is integral to their narrative strength. Nonetheless, encounters with examples of such wholly intelligent communication are few, and the exhibition appears overall to be more concerned with historical than with expressive significance.

Comments