Review: Friday @ Sheffield’s DocFest

June 17, 2016

Marianne Lambert’s portrait of Chantal Akerman, I Don’t Belong Anywhere – The Cinema of Chantal Akerman, began the Akerman retrospective with a useful primer for the uninitiated. Using a series of lengthy, informal interviews and clips from her major works, I Don’t Belong Anywhere bears some of the formal audacity that typifies Akerman’s oeuvre, which blurred the line between fiction and documentary to create contemplative and hypnotic cine-essays like Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975), News from Home (1977) and No Home Movie (2015). Akerman is an engaging subject, a peripatetic spirit with boundless curiosity. Hers was a truly avant-garde voice whose loss is keenly felt – Akerman committed suicide in 2015. I Don’t Belong Anywhere deftly explores the process and philosophy that underpins Akerman’s work. Her use of what Gus Van Sant describes as ‘against cinema time’, and her belief that ‘as soon as you frame something, it’s fiction’.

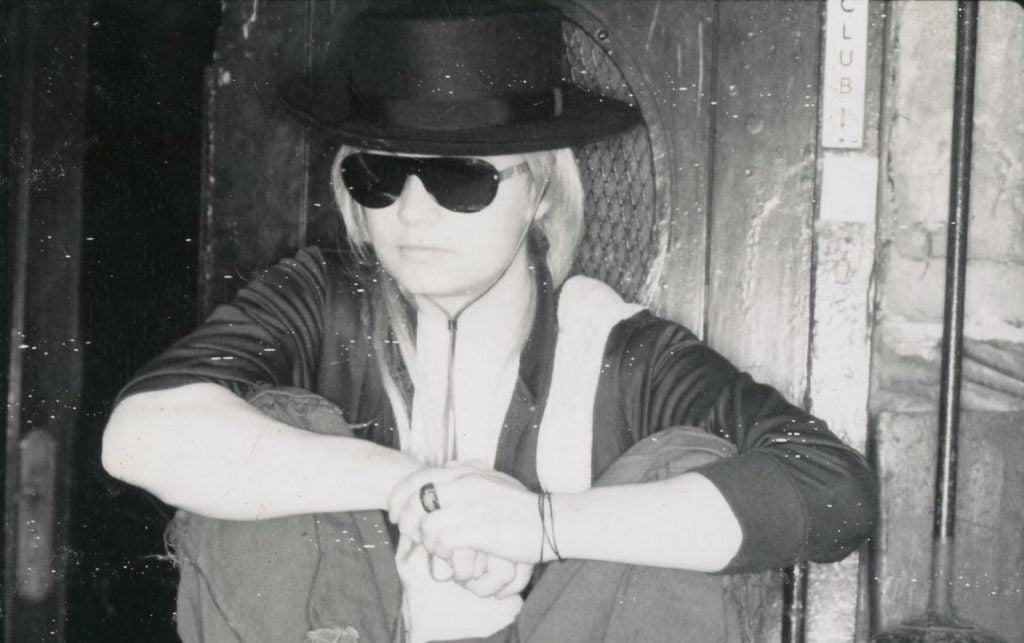

Author: The JT LeRoy Story is an engaging if uneven telling of ‘the greatest literary hoax of our time’: the rise of gay lit ‘it’ boy JT LeRoy. LeRoy became a literary superstar in the late ’90s with novels which claimed to dramatise his real-life experiences as the 13-year-old son of a ‘lot lizard’ – truck stop prostitute – against a backdrop of Deep South Baptist sadism. The novels read like Flannery O’ Conner filtered through William Burroughs, and propelled LeRoy to the kind of stardom seldom reserved for writers in the post-literary age. LeRoy was championed by celebrity surrogates who attended readings on the reclusive author’s behalf, and LeRoy began telephone friendships with indie luminaries like Courtney Love, Billy Corgan, Tom Waits and Gus Van Sant, all of which were recorded and detailed in Author. But there was only one hitch: LeRoy didn’t exist. LeRoy was the creation of a middle-aged mother named Laura Albert. Author details the perpetrating and sustaining of the hoax, and Albert’s deepening disenchantment as her creation overtakes her.

Author also speaks to a publishing industry engaged in a desperate search for novelty, authenticity and celebrity, the machine sustaining the eidolon in the face of an increasingly flimsy conceit. Director Jeff Feueurzeig has a pedigree for creating portraits of outsider artists, having previously made the spectacular The Devil and Daniel Johnston (2005), and where Author really excels is in its evocation of an alienated figure living through a series of avatars. Author explores the idea of identity as a form of creation, evoking the pre-internet age with its prominent audio component, reminding those old enough to recall it of a time when the telephone was the only gateway out. Less interesting is the section which details LeRoy/Albert’s entry in the charmed circle of celebrity and the unravelling of the hoax, which descends into tabloidy farce at times as LeRoy/Albert experience the fabled ‘Bono meeting’, schmooze their way through Cannes and grapple with the inevitable backlash of exposure. Ultimately, the hoax is less interesting than the perpetrator and what spurred her to commit it in the first place.

The banner event of the festival was the UK premiere of Michael Moore’s latest, Where to Invade Next. Like the anti-Bush Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) and the pro-universal healthcare Sicko (2007), Where to Invade Next is an election year broadside from the American left’s foremost populist agitator. The film’s conceit is that Moore ‘invades’ various countries and takes ownership of their best ideas, many of which originated in the US. Moore presents a series of contrasts to the US’s prison-industrial complex – its standardised, industry-tailored education system, the debt peonage into which US students have been plunged, and the failure of its Equal Rights Amendment.

Where to Invade Next is an entertaining but glib love letter to social democracy which has Moore’s customary wilful obtuseness and emotive register, but it finds Moore on much shakier ground, venturing into international territory about which he only appears to have the most cursory understanding. Moore has admitted that Where to Invade Next is aimed squarely at a low-information American audience, but many of his assertions are at best naive and at worst intellectually negligent, with humour used to paper over the gaping holes. It is in the nature of Moore’s work that thorny edges are snipped in service of rhetorical points, but his decision here to ‘pick the flowers rather than the weeds’ raises those old nagging doubts about his credibility.

Moore is to be applauded for his defence of everything the thirty-year neoliberal project has striven to dismantle. But to dismiss the peril at the heart of European democracy with a nonchalant shrug and ‘sure, every country has its problems’ feels like a gross minimisation of the fissures within these societies, with a resurgent far-right and austerity biting deep. The Sanders presidential run has the feel of an incipient movement, and Moore may be at the vanguard. But progressive change is more a matter of disposition than policy, and Moore seems to have little grasp of the cultural currents which threaten to overwhelm Europe’s fragile liberal consensus.

Comments