Being aware of the tragic backdrop for the album Skeleton Tree, which is at the heart of this documentary, most people will come to it with some trepidation. Am I intruding? Will it be too painful? The audience was totally silent, almost holding their breath: on edge.

The first person to appear out of the blackness is the familiar Warren Ellis. Good: the person Nick Cave says is holding it all together, his trusted friend and long time collaborator. But there is a problem with the filming and the interview has to be stopped and the film recalibrated. This does nothing to put the audience at ease – maybe purposeful, maybe not. It’s awkward and frustrating. And you just want to see Cave: check he’s OK.

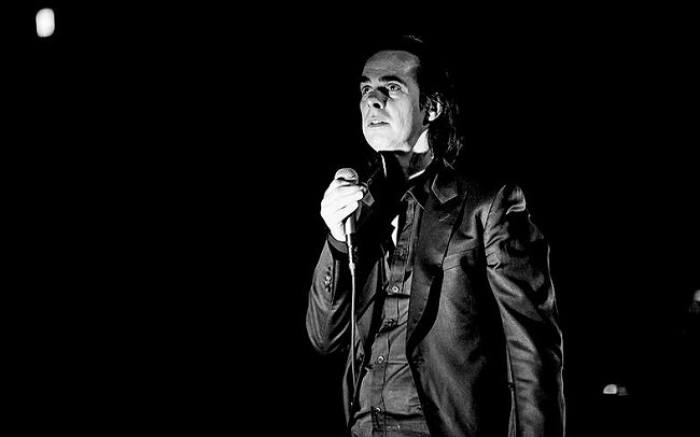

He appears. He is frustrated by the repetitive filming process too but manages to bring his usual warm humour. And the audience can breathe again. However, although he resembles the infamous Nick Cave, he’s not the same. He looks older. And there is some light missing behind the eyes. They are distracted. Guarded. He explains that the world is the same but he has to negotiate it now. You can tell. It seems that just focussing on talking is taking some effort. You almost don’t hear the words at times, as you are hypnotised by his worn face. The lines that tell one of the narratives he no longer believes in.

His narration, wonderfully poetic, is interwoven with these interviews and adds another dimension to the 3D. Almost undermining, unearthly, it sometimes overlaps so you are unsure what was filmed and what is voiceover: his thoughts as he struggles to find the chords on his piano, to make sense of the world. The frustration with himself. His self doubt.

Eventually he finds his voice for the first performance from Skeleton Tree and it is staggering. If you weren’t already aware you were witnessing something special then now you are. The sound envelops you. Ellis’s conducting is almost balletic, at one point controlling the camera with his actions as it moves in slow motion between him and Cave. Andrew Dominik’s direction plays with what is real and fabricated, the known and unknown that Cave is coping with, as the sound seamlessly moves between live and recorded. It jolts the audience and prevents them getting totally absorbed. This is not just a performance piece after all — this is the Bad Seeds. But you still want to stand up and applaud. And what do the musicians think? “Nice!” quips Ellis.

The film moves between the rehearsals, the interviews and the performances of the songs Cave hopes will “radiate out and connect with people.” And they do. How can you not connect when he is bearing his soul? The music is spellbinding, like a breathing entity. And as overused as the term is, the lyrics are this genius stretched to his optimum. Some of the songs are filmed as is, where in others, the camera takes you on a spiralling ride or ghostly journey through walls, there’s no passive listening.

Although the film remains in stark but beautiful black and white, it feels like a switch has been flicked when Cave’s wife, Suzy and son, Earl arrive. The singer lights up. You can’t help but be in awe as the couple broach the tragic death of their child, the event that they keep getting pulled back to. Cave says he now fears words and what they can expose about you. But as they struggle to find the words, they are totally exposed. Suzy says that she has no pearls of wisdom as she deals with her ‘physical depression’, but the courage they are demonstrating speaks louder than any words.

As raw and heartbreaking as One More Time With Feeling is (you are just about holding it together alongside them for most of the time) it is life affirming. As the film eventually transforms into colour, there is hope. And the couple, and those nearest to them, are drawing creativity from the pain and are being defiant in their love for each other and their decision to choose happiness.

Whether you are fan of Nick Cave or not, this is a must-see film. The cinematography is as breathtaking as the music. And it is a powerful portrait of a family living alongside grief. One of them just happens to be a musical icon. And you should definitely see this at the cinema. It deserves to be a shared experience. You will laugh out loud and cry. And you will feel grateful for the reassuring human connection during both, particularly at the end. The audience remained silent and still until the credits had finished rolling – one of the most heart-rending parts of the film. When the lights came up, it was like the end of a funeral, after the family procession, when you don’t want to move out of respect, and emotional exhaustion. But although stunned, people came out of the cinema smiling and embracing. And then went home, listened to the newly released album and connected again on social media, until the early hours.

Filed under: Film, TV & Tech

Comments