Review: Artist Roger Palmer’s Winter Garden at The Tetley

February 4, 2016

A haunting melancholy tinged with hope: the overriding theme that Roger Palmer’s current exhibition at The Tetley conveys.

A haunting melancholy tinged with hope: the overriding theme that Roger Palmer’s current exhibition at The Tetley conveys.

I visited Palmer’s Winter Garden with absolutely no idea what to expect, other than a purportedly huge installation of a palm tree which adorned the promotional flyers for the exhibit in miniaturised form. Having already walked around a typically sodden and overwhelmingly grey Leeds for the unenviable pleasure of having a vaccination, I was eager to get inside and explore Palmer’s presumably tropical display.

As I approached from Boar Lane and The Calls through a spitting rain and a viscous wind, The Tetley’s flag festooned art-deco exterior slowly became visible amongst the other post-industrial buildings and rubble-strewn carparks found just south of the river Aire. After being somewhat ignominiously closed as a functioning brewery in 2011, The Tetley has since used its considerable acreage and vaulted chambers to play host to a variety of functions, becoming everything from an art gallery and learning centre to a prime venue for summer music festivals.

Once I had passed through the old brewer’s entrance and ascended to the first floor via a worn mahogany staircase made smooth as marble, the interesting choice of The Tetley as a venue for an art and photography exhibition started to make more sense once I had seen Palmer’s work.

His exhibition is an amalgamation of photography, wall-drawings and other mixed media installations. Born in Portsmouth in 1946 and having graduated with an MA from the Chelsea School of Art in 1969, Roger Palmer became a prolific artist and photographer, the recipient of multitudinous awards and the architect of a plethora of photographic catalogues dating back over the last 40 years. Collections of Palmer’s photography work are laid out across numerous rooms on the first floor, spread out like spokes on a wheel around Palmer’s centrepiece, the gargantuan mural of a palm that I mentioned earlier. Towering in the middle of a vast atrium and illuminated naturally by skylights, Palmer’s titanic monochrome palm-tree seems to encapsulate exactly what he’s driving at with the whole exhibition.

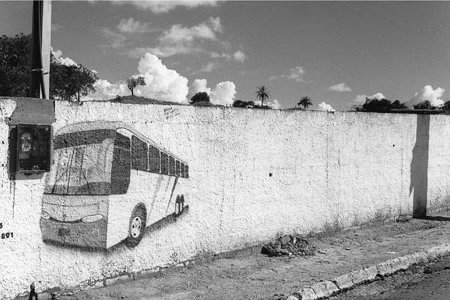

Palmer’s work engages with a post-colonialist narrative. Many of his collections depict tropical locations; beaches and palms of Nauru for instance, that are somehow scarred by the presence of man and the impact of industrialisation. Another example of this is a collection laid out showing ‘the sinking of the SS Konigsberg’; here photographs of the rusting hulk of the German warship, fired upon and sank by the British in 1915, are further contrasted with the idyllic east African beach location, the metallic carcass of the ship another vulgar reminder of humanities’ often unintentional destructive impact upon vulnerable nature. These are often paired with photographs of urban Portsmouth and Leeds, a guilty confession from a denizen of the country that gave the world industrialisation that so wantonly wreaks despair in Palmer’s tropical photography.

An installation found directly opposite the Palm mural is perhaps the most overtly indicative of Palmer’s overarching Winter Garden narrative. Titled In The First Hour Of Daylight, Palmer uses a series of nigh-identical monochrome beach landscapes depicting the same pair of palm trees across 11 days. The scene is nothing short of elysian, however Palmer also uses printed text in this section to tell the colonial story of Nauru; the highs and lows of the island’s history under first British, then German rule and its eventual fate as an Australian migrant detention centre. This blissful scene is further contrasted with a tale of phosphate mining amongst coral reefs, which despite initially yielding wealth for the Island, eventually brought down upon it financial devastation and environmental desolation. Which in turn is heightened by Palmer’s decision to capture such an obviously colourful and seemingly perfect scene in a monochrome effect; all is not what it seems and it’s our fault.

Despite the doom and gloom, there is optimism here. I couldn’t help but notice the palm tree Roger Palmer uses as the focal point for the exhibition, sourced from a 1915 horticultural engraving found by the artist in a Johannesburg bookshop (the original book is also on display), was called Acanthophoenix Crinita which struck me as significant. Palmer’s chosen variety of palm is more deadly than it looks, concealing a series of thorns beneath a leaf sheath, and like the phoenix it takes its name from, is resilient and will endure against the onslaught of humanities’ destructive encroachment. It is of course worth mentioning here that The Tetley too is doing its best to shed the ashes of its industrial past to become something new.

I came to The Tetley expecting Palmer’s exhibition to shelter me from the gritty Yorkshire winter raging outside. However Winter Garden is no whimsical installation to warm the heart; it is a powerful statement, a stark warning against the post-industrial wasteland we are threatening to create in some of our most beautiful and precious environments. Its placement in an ex-brewery, in the heartland of a region that powered the industrial revolution, becomes all the more poignant as you take a walk around the exhibition and Palmer’s sad, scarred but hopeful message dawns on you; as expressed here in Palmer’s own words, “This work is about loss, mortality and a nature that feels hope, along with the fragile life of things.”

A visit to the Tetley is therefore compulsory for anyone familiar with Palmer’s work, essential for the environmentally and artistically conscious, and quite possibly vital for the future of our planet.

Comments