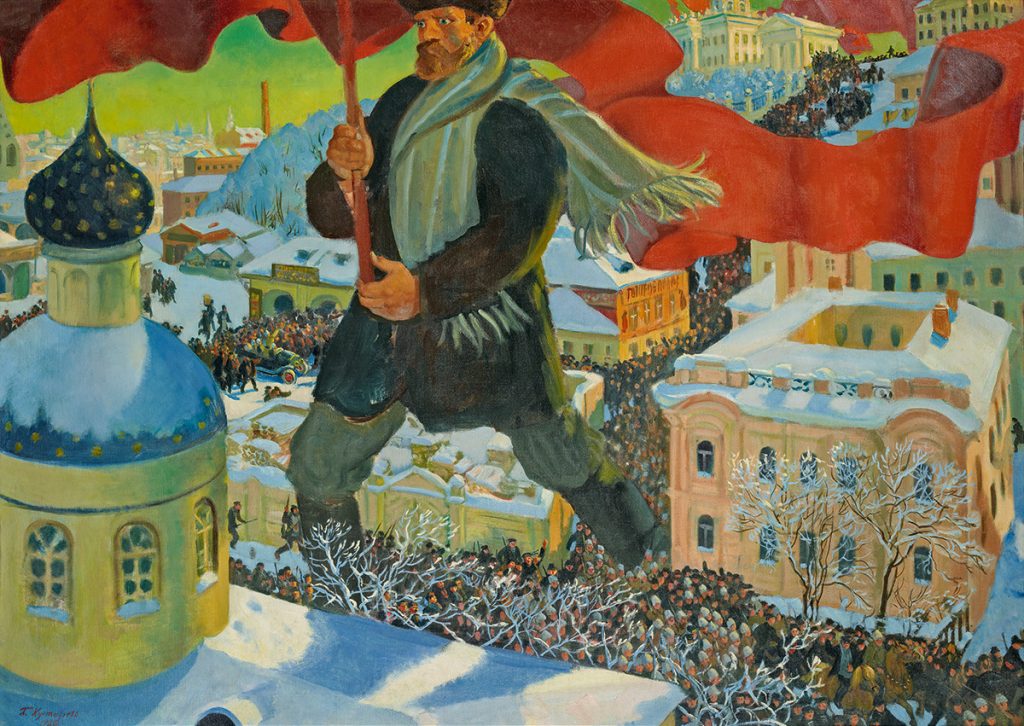

Boris Kustodiev, The Bolshevik, 1920

“All Power to the Soviets”, demands a banner hanging above our heads, white Cyrillic on red fabric. It is 1917 and the Bolshevik Party is ridding Russia of its Tsarist regime and liberating the people with socialist revolution. A re-creation of those wielded by eager proletarians, the banner incites collectivity and triumph. Marking the centenary of the Russian Revolution, the Royal Academy exhibition opens with key players of this tumultuous time: the noble proletarian, the valiant masses, and, of course, the fearless leader.

Seated before a crimson curtain high above the masses, Vladimir Lenin fixes his enigmatic gaze upon the viewer. Alone in a room he pores over papers, writing scripture for the future. His inimitable features appear everywhere from crockery to headscarves, a sacred presence of the new regime. In a corner across, Joseph Stalin waits patiently, successor to this cult of personality. Giants are once again at the helm.

But this is the people’s revolution, so art must celebrate the people as they step into the limelight of history. Peasants and ‘shock workers’ are the superhero of the age, an identity for every man and woman to adopt. Strapping youths turn great wheels and cogs or bask before new machinery. Proud individuals in Aleksandr Deineka’s Construction of New Workshops (1926) play their part with zeal. No longer labouring for the profit of others, workers everywhere embrace industry as the lifeblood of a better society. Utopia is on the horizon.

Isaak Brodsky, V.I.Lenin and a Demonstration, 1919

Artists sought to celebrate the political turbulence and unprecedented diversity of the era. On the one hand, Boris Kustodiev’s monstrously proportioned Bolshevik (1920) striding over onion-domed churches, red banner aloft, is a folkloric imagining of the masses. On the other, Kazimir Malevich’s Red Square, abstract at first, subtitled Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions, is a modernist homage to the revolution. It all culminated in a 1932 exhibition Fifteen Years of Artists of the Russian Soviet Republic, the inspiration for the RA’s curation. Through the clamour of contradictory styles, we picture the people’s revolutionary fervour as a whole plurality of voices dying to be heard as the new regime swept away the old.

For avant-garde artists, the revolution provided liberation, creative on top of social, and offered the chance to finally rid themselves of the yoke of academic convention. Kandinsky, Chagall, Popova. Painting after painting by Malevich hung to mimic the 1932 exhibition embodies the elation felt by many modernists.

Nevertheless, as Red Square indicates, the Bolshevik agenda and promise of civic empowerment was central to avant-garde work. Faces that swim in and out of the picture-plane in Filonov’s Formula of the Petrograd Proletariat merge with their mechanised surroundings in a manner that both echoes cubism and recalls collective spirit. A life-size mock-up of El Lissiztky’s design for a Soviet apartment, Spartan and simple, provides only the essentials for occupants to fill, a blank canvas that is both a Suprematist ideal and a leveller of class. Avant-gardism could at last enjoy a time where their aspirations aligned with political aims, and their ideals could become realities.

Filonov’s Formula of the Petrograd Proletariat, 1920-1921

Revolution was not, however, welcomed by all. Despite initial success, the Bolsheviks’ 350,000 followers were still a minority within the country’s 14 million population, and civil war broke out when change had barely begun. Struggle for control, exacerbated by famine and disease, left the populace impoverished. Paintings emerged featuring peasants and a folkloric, nostalgic pining for a lost Russia. A growing sense of uncertainty threatened to undermine the Communist agenda already wearing thin. But by 1928, Stalin’s first Five Year Plan instigated a repression of ancient peasant culture and the values that went with it.

The encroachment of politics into the world of art was something Lenin had introduced as early as 1918, when he announced his Plan for Monumental Propaganda. Now Abstraction fell out of favour. The 1932 exhibition, in all its plurality, was to be the last of its kind. Two years later, Stalin announced Socialist Realism, and demanded that art serve the purpose of the regime. So it was that art came to present Mother Russia as thriving and indomitable, when the reality was that millions remained impoverished and dying.

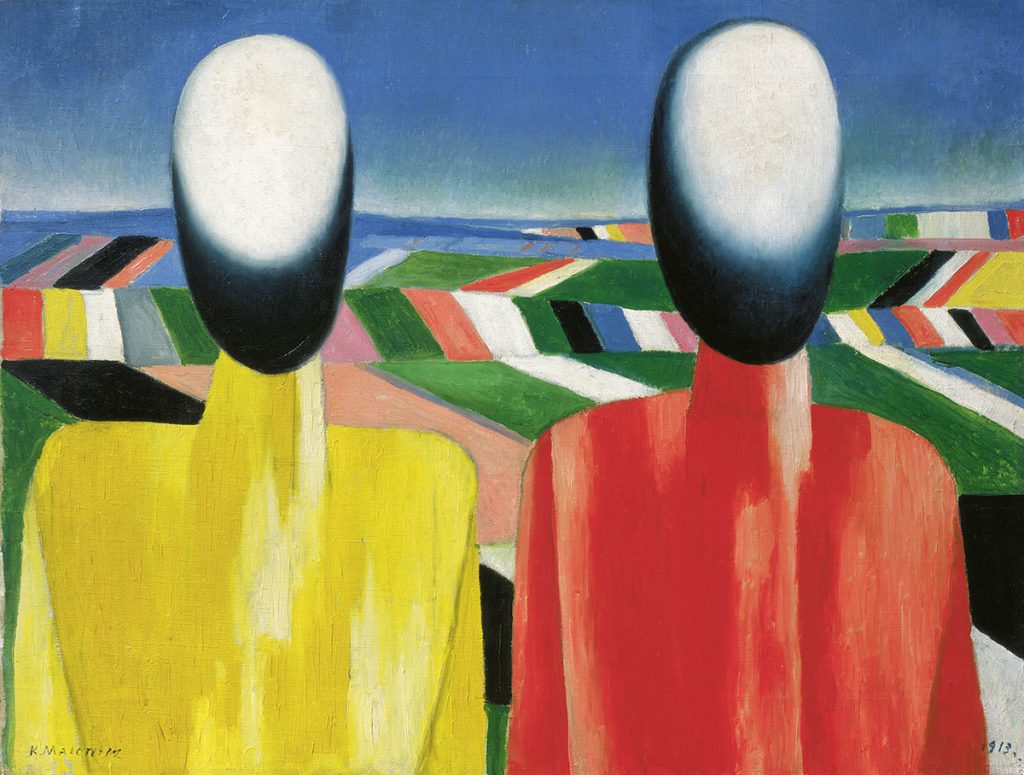

Malevich, Peasants, c. 1930

Few artists posed any opposition. Those who did did so cautiously, offering the subtlest dissent. Malevich’s later use of faceless figures suggests disenfranchised individuals. A room devoted to the work of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, whose style was Socialist Realism, echoes Lissitzky but reveals the depravity of existence in Russia and an anxiety growing within populace. The Soviet bubble had burst: in a chamber of its own, a prototype of Tatlin’s flying machine twirls endlessly above us, a dream never realised.

Crucially, this exhibition reminds us that the story didn’t end in 1932. In a corridor of mural installations we see the next generation again coerced to rally for a revolution supposedly still being realised. Again the proletariat, sport, and the ideals of youth are celebrated. In the Room of Memory, we see slideshows of those exiled or executed or sentenced to the gulag under Stalin. Finally, the inescapable image of Stalin returns, in paintings, photographs, and, like Lenin before him, on everyday objects. To have traversed the outpourings of such a tumultuous period, and to have reminded us that what euphoria existed at the time turned sour so quickly, is an impressive feat.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Comments