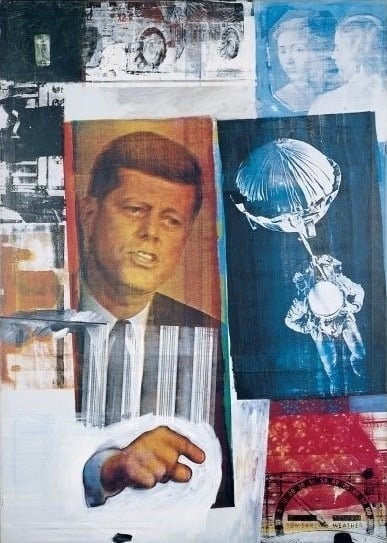

Retroactive II (1963)

Tate Modern’s retrospective of esteemed and highly influential artist Robert Rauschenberg presents a broad range of techniques, materials and messages that span multiple movements and influences. Rauschenberg and his infinitely various, trailblazing work cannot be defined using any umbrella terminology.

Rauschenberg launched his career in the early 1950s when abstract expressionist painting was at its height. One of his works in the first room of the exhibition responds to the movement. The untitled black painting made in 1951 is an abstract work which the artist described as “night plants”. Rauschenberg soaked his canvases in paint, so the process does not involve any interaction between paintbrush and canvas. The sinister black mass dominates the wall of the first room and demonstrates how Rauschenberg subverted the appreciation for brushwork which was upheld at the time. His early work continually pushed the boundaries of the world that it entered into. ‘Scatole Personali’ consists of a series of small boxes that emphasize the properties and aspects of different natural materials. The piece was extremely controversial to the public when it was first exhibited. It could be argued that while drawing from the religious allusions made to reliquaries containing the body parts of saints, the piece undermines the Catholic tradition in the process. However, as is the case with many of the works shown, multiple readings can be drawn and Rauschenberg could be revealing an appreciation for the natural world in this piece, claiming that it too should be worshiped.

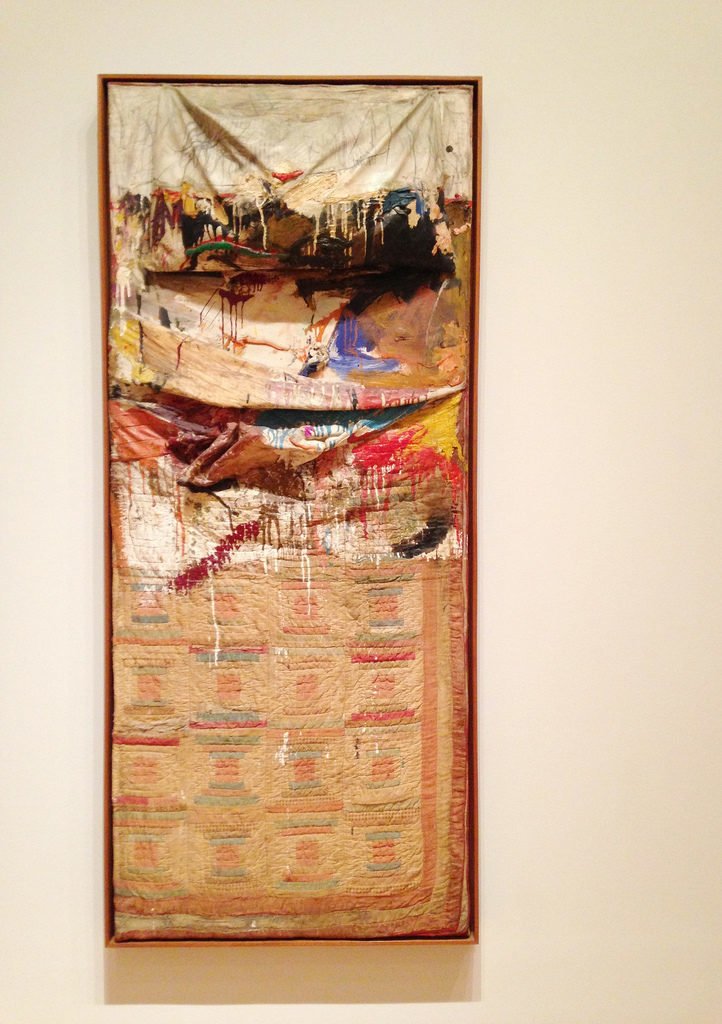

During the mid 1950s, Rauschenberg started including objects in his paintings making them ‘awkward physically’. One could agree that there is a certain discomfort in the amalgamation of sculpture and textured painting in each of the series named the Combines. In Rauschenberg’s installation ‘Bed’ he used a patchwork quilt given to him by artist Dorothea Rockburne as he could not afford to buy a canvas. Though many viewed the work as aggressive and unsettling the artist claimed that it was one of the ‘friendliest’ pictures that he had ever painted. While perhaps the sentiment of the gift and comfort of the quilt can be felt by some, the scratching drawings down the top of the pillow and mattress and bloodlike dripping of paint down the empty bed renders it not only awkward but sinister and indeed unsettling.

Bed (1955)

Each room introduces another dramatic change in technique and form as Rauschenberg inspires, and draws inspiration from, the altering world around him. The silkscreens of the 1960s demonstrate Rauschenberg’s attempt to capture society and offer a ‘window’ to the outside world. The prints layer images from famous figures on television, historic pieces of art, and pictures from the media. Additionally, paint is used to emphasize certain elements, such as President Kennedy’s hand in ‘Retroactive II’, which is heavily outlined in white, making it reach straight out to the viewer. Another interesting turn is taken in the Material Abstraction room where one walks along a series of opened-out cardboard boxes. This process radically alters their shape and, though they become obsolete in terms of their original purpose, they take on an entirely new meaning. One blue box is opened out to resemble a butterfly or some kind of kimono as Rauschenberg transforms the raw and industrial into the refined and beautiful.

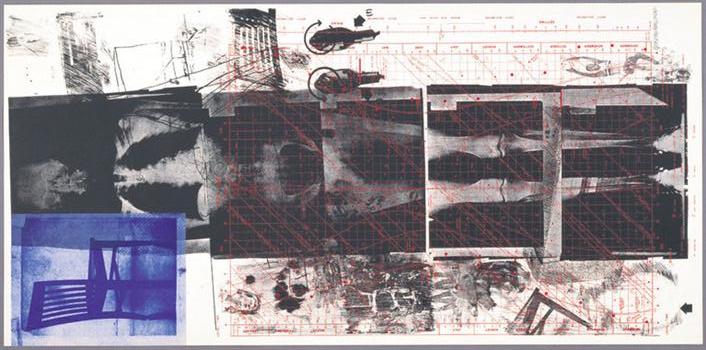

Booster (1967)

In the final room of the exhibition, which exhibits Rauschenberg’s later works, made in the nineties and noughties, the walls are covered with his large scale pieces involving photography made with the then-new technology such as Iris inkjet printers. The images included were taken, or carefully selected, by the artist. They range from the personal, such as a full early x-ray of Rauschenberg’s own body, to general photographs of public places. However, each image possesses a hidden alternative view of things that we are used to seeing everyday and the works offer intimate observations of the world around us.

Tate Modern describe Rauschenberg as having a “generous and experimental approach to art-making” and while the multifarious, multimedia work in this retrospective can initially seem overwhelming, it is also as rich as it is varied and offers fascinating insight into how Rauschenberg drew everything around him into his work, and truly did, as he put it, “act in the gap between art and life”.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Comments