Should you ever be trying to fight your way from Central to South East London, particularly on a crisp February morning like yesterday’s, a Thames boat ride is a civilised alternative to the DLR. While you make the most of the winter sun, a glance northward between Temple and Tower Hill will provide perhaps the most complete view of the area razed by the Great Fire of London.

Should you ever be trying to fight your way from Central to South East London, particularly on a crisp February morning like yesterday’s, a Thames boat ride is a civilised alternative to the DLR. While you make the most of the winter sun, a glance northward between Temple and Tower Hill will provide perhaps the most complete view of the area razed by the Great Fire of London.

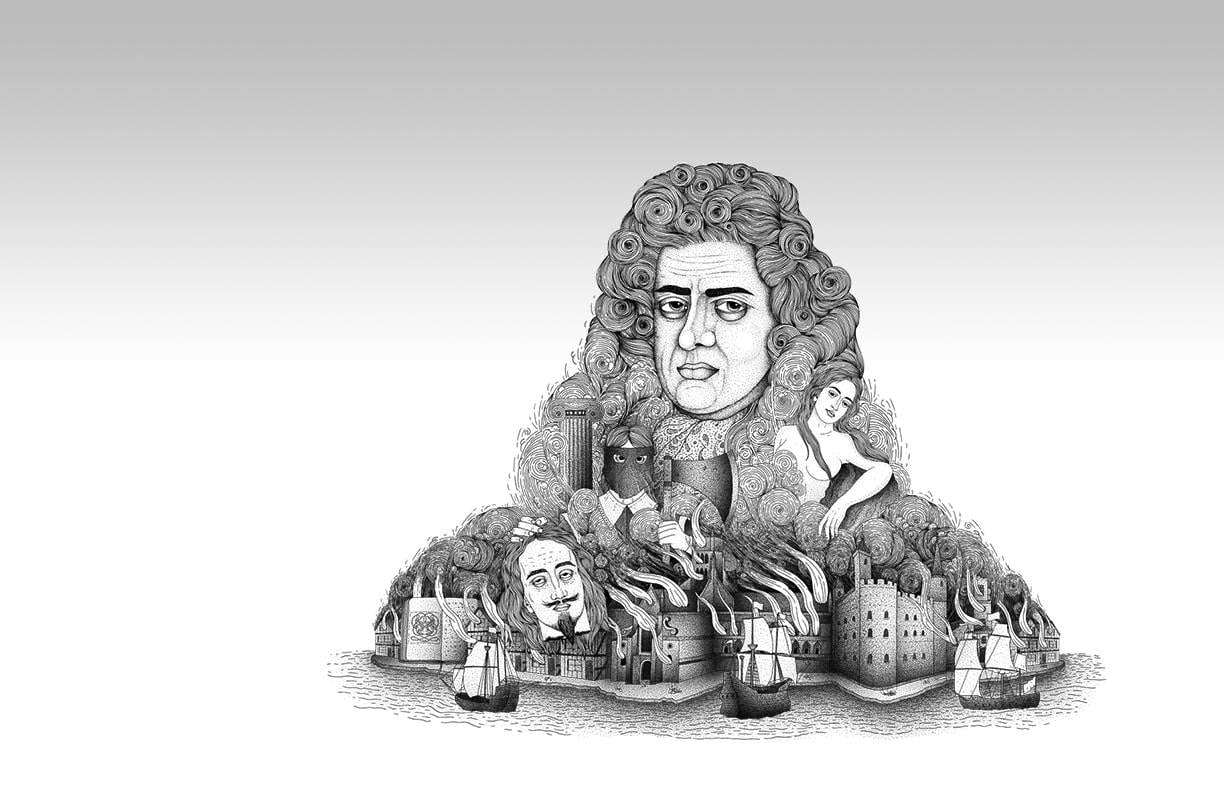

The stretch is almost a mile long and the fire spread as far as half a mile back from the river, destroying 13,500 homes, 87 parish churches, the Royal Exchange, and who knows what other treasures and works. But among those who were able to save their possessions, and so continue his account of an intensely eventful period in English history, was Samuel Pepys, a naval administrator and member of parliament, whose diaries are currently being celebrated at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, where I, my father, and my grandfather disembarked.

The wealth of history in the small gallery housing the exhibition is testament to the depth of Pepys’s involvement in the life of mid-17th century London. You will find a well-worn pair of embroidered leather gloves, purportedly removed from the hands of Charles I a few minutes before a 15-year-old Pepys watched, approvingly, as the King’s head was removed from his shoulders.

Pepys would later attend the coronation of Charles II in 1660, five months after commencing his diaries, and the exhibition includes a magnificent 2.8m x 2.4m oil-on-canvas portrait of the restored monarch, dressed in parliamentary robes and holding the Sovereign’s Orb, painted by John Michael Wright in 1675. Nearby can be found the letter sent to The Hague by seven MPs in June 1688 inviting William of Orange to invade England and depose Charles’s catholic successor, James II, an invitation William accepted four months later.

A digitised map plays out the spread of the Great Fire (news of which Pepys was the first to deliver to the king), accompanied by audio commentary from Pepys’s account. The graphics well represent not just the pace of the fire, but how great a portion of the then-smaller London it consumed (a note on one of the walls says that in later life Pepys ‘left London and retired to Clapham’).

Elsewhere is a small reflecting telescope made by Isaac Newton in 1671. Pepys was president of the Royal Society when, in 1686, Newton’s Principia laid the foundations of classical mechanics, and his name appears on the title page of the work, though he would probably have understood little of its contents. Newton would later follow in Pepys’s footsteps, becoming the society’s president in 1703.

While we were there a free talk took place delineating how Pepys’s political alignments evolved throughout his life (conclusion: so varied were his allegiances that one can argue he was neither a Royalist nor a Republican, but an opportunist). The talk was given informally in one corner of the gallery and was clearly not audible to many of the 30 or so people stood around us, but this is a problem easily rectified, and the discussion was an engaging exploration of a topic perhaps too speculative to commit to section labels.

Anxious about the failure of his eyesight, Pepys stopped writing his diaries in 1669, but had them bound in six volumes and stored in his library. Despite the measures he took to save and preserve the diaries, it is doubted Pepys ever intended them to be published—he left them in shorthand form. In 1819, a Reverend John Smith set about transcribing them, and would work for two years before realising which shorthand system had been used—Thomas Shelton’s Tachygraphy—or that the code to decipher it had been in Pepys’s library the whole time. Smith’s original transcription can be seen opened to the final page, on which Pepys prays: “All the discomforts that will accompany my being blind, the good God prepare me!”

We are fortunate that Pepys wrote and recorded while he did and that Smith laboured, however unnecessarily (though I should confess that our party of three included only one member, your unfit correspondent, yet to take advantage of the fact). Samuel Pepys: Plague, Fire, Revolution provides a rich introduction to the subject, and is a service not just to the history of the diaries themselves, but to that of the events that bore them.

The exhibition runs until 28 March 2016. More information can be found on the Royal Museums Greenwich website.

Comments