My eyes first began their ironic roll when on the morning of Trump’s victory my sister sent me her first university essay to read—all about the influence of the American Revolution and its ideals of liberty and equality on subsequent political changes in Europe. They were sent into a dizzying spin when I went to see You Say You Want A Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-1970 at the Victoria & Albert Museum, an exhibition celebrating the years 1966-1970, when everything changed and the world became one where freedom, tolerance, individuality, and equality were the driving forces.

Ha.

Immersive, as all exhibitions these days are, a set of headphones blares out records from John Peel’s enviable record collection as visitors are taken through seven exhibitions covering changes in youth identity, the head and thinking (and the impact of mind-altering substances on this), the street and political movements, consumerism, living, communicating, and its ongoing legacy.

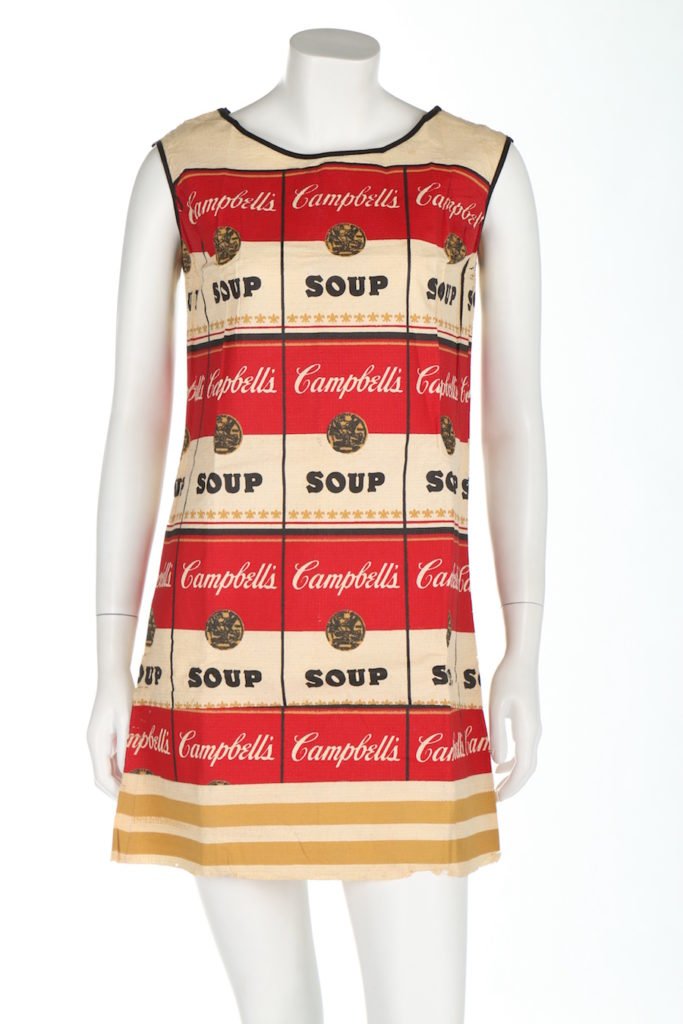

It’s busy, throngs of people indulging in nostalgia battling to see the exhibits. This isn’t a revisionist interpretation, but is fairly broad in approach with a whole range of objects, photographs, ephemera, literature, posters, and footage from the five years in question. There’s the familiar Sgt. Pepper outfits, Woodstock footage on a big screen, and cushions on which to lay back and watch The Who, the swinging Carnaby Street and Twiggy outfits, Warhol soup cans and Profumo scandal—but it’s the smaller details that stand out.

The Souper Dress, 1966. Photo: Kerry Taylor Auctions

Arguing that this was the era that started environmentalism, we see visionary Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog; there’s the 1966 advertisement for the credit card that is ‘All a girl needs when she goes out shopping’ (even though she could not take one out in her own right until 1973); alongside newsreels of the demonstration we see American soldiers’ letters home from Vietnam; and as well as quotes from Osborne’s Look Back in Anger (19560) and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (the DH Lawrence novel first published in 1928 but not cleared from censorship until 1963) we see the Buckminster Fuller book of 1969: Utopia or Oblivion.

A growing disillusionment with leadership and modernism motivated an increase in political engagement. This was the era that civil rights, gay rights, women’s equality movement, and black liberation all, it is argued, became mainstream—a thought that seems optimistic right now. Nonetheless, the bold and persuasive rhetoric on show such as posters from prisoners from the Attica State Prison and Atelier Populaire offer a window into the hope that people then and now have.

As the catalogue explains, curators Victoria Broakes and Geoffrey Marsh aim to show that whilst in 1965 Britain, homosexuality and abortion were illegal, only married women were eligible for the pill, divorce was difficult, the death penalty still existed, censorship was in force and racial discrimination common, things had dramatically changed by 1970. By the start of the new decade, tolerance, liberation, and acceptance were the norm. Again, right now this argument that threads through the exhibition seems questionable.

Let us hope that these ideals do not remain in the museum of yesteryear, but continue to be just as thrilling and exciting as they were in those revolutionary years of 1966-70.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: American revolution, Geoffrey Marsh, Sgt. Pepper, Stewart Brand, V&A, Victoria Broakes, Woodstock

Comments