Phill Hopkins is a British contemporary artist who works from his studio on the edge of Leeds, which offers access to walks through the countryside. Working across a range of mediums from the traditional to the unconventional, he is predominantly a painter who makes drawings, photographs, and sometimes sculpture.

Raised in a working-class family in Bristol, he found school difficult but excelled at art. He went on to study at Goldsmiths College of Art in London and has exhibited in museums and galleries including The Imperial War Museum, Kettles Yard, Laing Art Gallery, Hungarian Museum of Photography, Whitworth Art Gallery, Leeds Art Gallery, John Hansard Gallery, The Usher Gallery and The Henry Moore Centre for the Study of Sculpture.

Court Spencer went to his studio to talk about his practice, current shows and plans for the future.

Fennel tea in the studio.

Court: Ah, it’s always nice to visit you in your studio and have some sort of herbal tea fresh from the garden! Do you love having your studio at home?

Phill: You’re very welcome here! I do love it, especially the 5-metre commute! My studio sits here in the back garden, accompanied by our wildflower meadow and pond. There are bird boxes on the side of the studio, and I’ve been watching a pair of great tits moving in. And the front garden is a veg plot, where I picked the fennel for your tea. I like working at home. I spend hours in the studio but can also just pop in for a few minutes.

My brother-in-law, the artist Jake Lever, recently remarked that he felt that my studio is a happy place.

Court: It really does feel like a happy place. How long have you had it and did you ever have a studio space away from the house?

Phill: I built the studio with Sam, one of my sons around 13 years ago. When I first came to Leeds I moved into a studio on the banks of the River Aire. It was an old warehouse with thick walls, cold in the winter and still cold in the summer! It was good to be in a community of artists but as the city developed it became increasingly difficult to find affordable spaces.

I then moved to an attic room in the house that I was living in. It was very different, but I enjoyed the solitude, and my children could work alongside me when they wanted to. I don’t think I could go back to sharing a space – there would be complaints about my music.

Court: Haha, you’d just need some good headphones! You’re pretty prolific with the amount of work you make. Do you have a routine or any studio rituals?

Phill: I find it hard not to make work. Making is a way of processing both my internal and external worlds. I’ve always worked hard. At Goldsmiths I was known for my work ethic. Most days I come to the studio around 9am to start work but sometimes I come in very early in my dressing gown to look at what I did the day before.

I remember my former teacher and friend Carl Plackman said to always leave something unfinished so there’s always something to do the next day.

I begin with putting my music on. Sometimes I watch a film whilst working. I like my head to be occupied with something else whilst my hand and gut work. When I’m working on something I’m always impatient to get it finished and start something else; I’m never stuck or blocked, for ideas!

Circa 1982 Phill Hopkins in Bristol on his Foundation Course.

Court: It feels like your work covers different periods of interest. Can you talk us through some of those?

Phill: A question like this is rather daunting because I don’t have a neat answer. Over time I’ve made a lot of work about conflict, whether that was to do with external political unrest or my own internal personal world. Since my late teens, I’ve been moved to make work related to the political. I remember when I was around 19, listening to Sandinista! by the Clash and making work about Ronald Reagan. I’ve always been drawn to defend those whom I consider to be the underdog.

I made a series of paintings about Syria, images of women and children fleeing a bombing raid. In order to work out how I feel about something, I’ve always needed to make a visual response, that’s how I process. This all came to ahead when the UK voted to leave the EU and later Trump was elected president in the USA. I felt despair. I didn’t know how to respond.

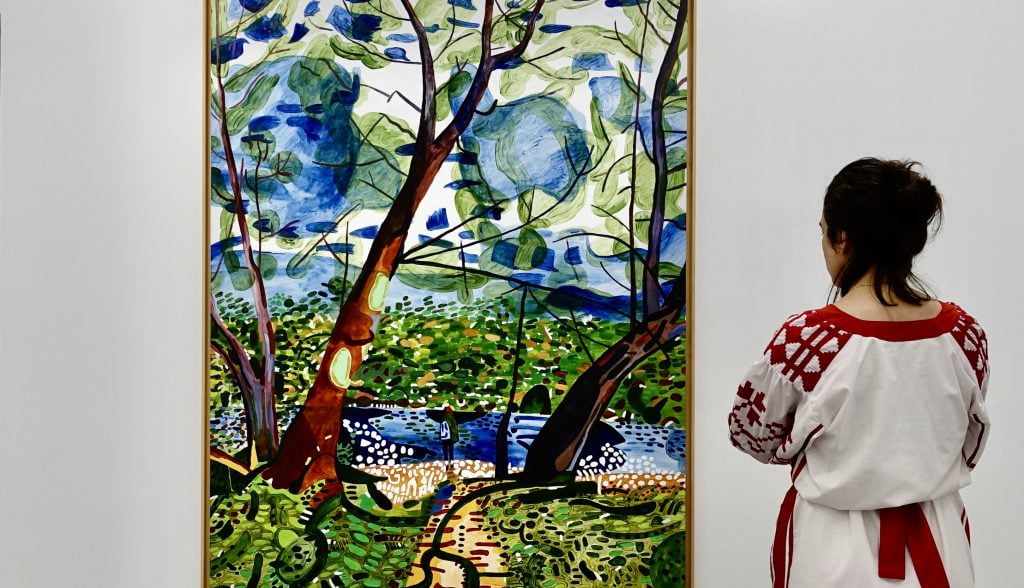

Out of all of this came a return to the land or the landscape. I made a large series called ‘Post Truth’, paintings based on my photographs I made in Pembrokeshire of the sea. I know the landscape, I grew up on the edge of Bristol, it was my playground. I felt I needed to connect with it again. I didn’t plan for it, it just happened.

The time gifted to us by the COVID pandemic was important for me. I had space to find my feet, to rebalance myself and focus away from myself. During this time I made a lot of work around my ‘Walking Ahead’ series. On the surface they might seem colourful and romantic, but underneath there is a strong seam of personal distress and perhaps themes of being alone or loneliness.

Two large paintings in progress in the studio as part of the series ‘Walking Ahead’.

Court: I know you’re a big fan of Sidney Nolan and Australian Aboriginal dot paintings. What is it about these that interests you and what other artists or historical references influence or inspire your work?

Phill: I am captivated by Nolan. I love the honesty and direct nature of his work. I love the adventure and excitement of both his subjects and his experimental use of materials. I think this is connected to my friend Julia, who went on an Operation Raleigh Expedition to Australia in the 1980’s. They were tasked with finding and registering aboriginal cave paintings before white farmers, whose land they were on, found them and whitewashed over them.

She was working for the underdog, and this really resonated. I’m interested in how with the hangover of white colonialism, we might see land, like the outback in Australia as empty. But having spoken to aboriginal artists, I understand that there isn’t an emptiness at all, but a complex connected system that runs through the whole of creation and the natural world. And the way those artists make marks and use symbols really excites me.

I also look at lots of other artists, Philip Guston, Robert Rauschenberg, Kiki Smith, Milton Avery, lots of German painters, David Hockney, Edvard Munch, to name a few. If I like the look of something, I just borrow it and use it in my own work.

Circa 1980 Phill Hopkins painting in the back garden in Bristol.

Court: You mentioned earlier that you grew up in Bristol. What was that like? And then did you go straight from school to Goldsmiths?

Phill: I loved growing up in Bristol. I come from a large post-war council estate in the south of the city. Looking back now, we were quite poor. My parents worked in labouring jobs and it was very hand to mouth. It was a safe place and full of adventure. I played outside and drew constantly, I had a deep relationship with the land and even in the middle of winter we would make igloos from the snow.

I didn’t do very well at school, but thankfully got to do an art foundation course. After a month I left as I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. I got a job in a warehouse, a bakery and a pub. But I started to make pictures again, drawings and constructions and 2 years after leaving, I went back to the course, and I loved it!

I visited Goldsmith’s and thought this is where I want to go. So I applied and they gave me a place. It was a wonderful three years, I was in the right place with the right people, although there were only a few of us with regional accents. It was heavenly.

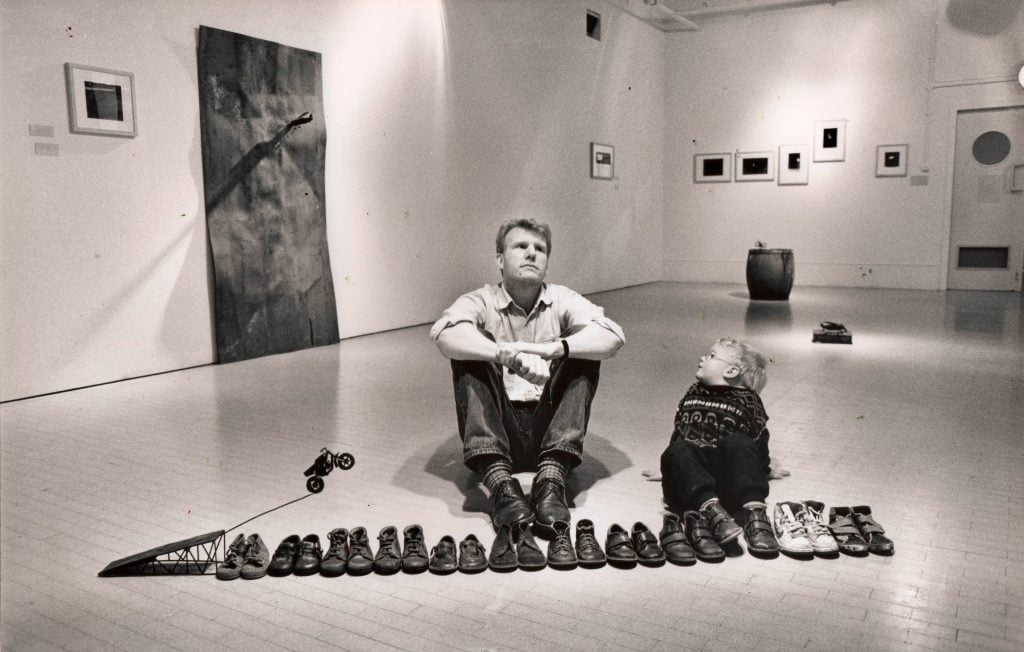

Phill Hopkins 1991 Leeds City Art Gallery – Flyers exhibition – with Joshua Hopkins and sculpture ‘Jumping Feet’.

Court: That great that you went away and then came back and got so much more from the experience. You’ve since gone on to shown in some incredible institutions and your work is in some impressive collections. What are some of your career highlights to date?

Phill: I remember how exciting it was to be included in the New Contemporaries at the ICA in the early 1980’s, when I was at Goldsmiths. I showed a large rug made from sheet steel. Time Out said I was a “figurative Carl Andre”.

My solo show at Leeds Art Gallery was a lovely experience working alongside Dr Terry Friedman, who was a great champion of my work. Works from that show were acquired by the Imperial War Museum and later shown at Kettle’s Yard, which was thrilling.

I was invited by Pangolin Gallery, London to show in ‘Carl Plackman and His Circle’; it was lovely to show alongside fellow alumni from Goldsmiths, like Damien Hirst and Jonathan Callan, also former teachers like Richard Wentworth, Alison Wilding and of course Carl himself. Connected to that show was an invitation to show in ‘Step and Stair’, co-curated by Dr Jon Wood, at Art Space Gallery in London, sharing the space with Carl and others including Basil Beattie and Leon Kossoff.

In 2021 Galeria Fernando Santos, in Portugal, asked me to make new work for a show. I worked like crazy and loved it. The show ‘Some Paintings with a Figure and Some Without’ opened in June 2022. I made twenty-five large paintings, ten A1 sized drawings and an even bigger painting for the show. I feel honoured and thankful to work with Fernando and his team and Porto is wonderful.

Work in the studio prior to the show at Galeria Fernando Santos, Portugal.

Court: Do you have a dream project you would love to make happen?

Phill: I’ve never been to Australia, and I’d like to go. I feel an affinity, if that’s the right word. I have messaged Aboriginal artists on Instagram but would like to meet them in-person to talk about painting and watch them make work. An Australian friend introduced me to the colour ‘Australian Sienna’, which I use a lot and I’d like to hold that in my hand. I’d love to observe and participate in the landscape and make work there. It’s too late now to meet Archie Roach or to hear him live, but there are others I’d like listen to. Having said all of this I’m deeply troubled by my colonial past and wonder whether I should just stay in Leeds and not make any more trouble.

The exhibition “Some Paintings with a Figure and Some Without’ at Galeria Fernando Santos, Portugal.

Court: I’ll have to give you some of the ochre an Aboriginal Elder gave me last time I was home. What are you working on at the moment?

Phill: ‘Town & Country’ has just opened with Jonathan Hooper at Cole’s Gallery, in Leeds. I’m delighted with how it looks. I discovered Jonathan in lockdown. He lives and works very close to where I am and instantly thought there’s an intriguing connection between our work.

I’ll be showing with Kadip Gallery at the Affordable Art Fair in Hampstead in May. I’ve just finished three paintings for that to go alongside a ‘Walking Ahead’ piece and an edition of prints.

Working with you and The Art Court is progressing nicely. We’ve got some interesting plans growing, including the Knaresborough Series, a suite of prints that have just been released and can be seen outside Indigo Mill on Waterside in Knaresborough or online.

Signing the ‘Knaresborough Series’ limited edition prints.

Court: What’s the best way for people to keep in touch and see more of your work?

Phill: I like Instagram, so there’s a lot to see of me there and my website has all the added extras.

Court: Thank you so much for having me over. It’s always such a treat to see what you’ve been working on.

Filed under: Art

Tagged with: Aboriginal art, art, artist, contemporary, dot, drawings, exhibition, Goldsmiths, leeds, photographs, sculpture, solo show, Studio

Comments