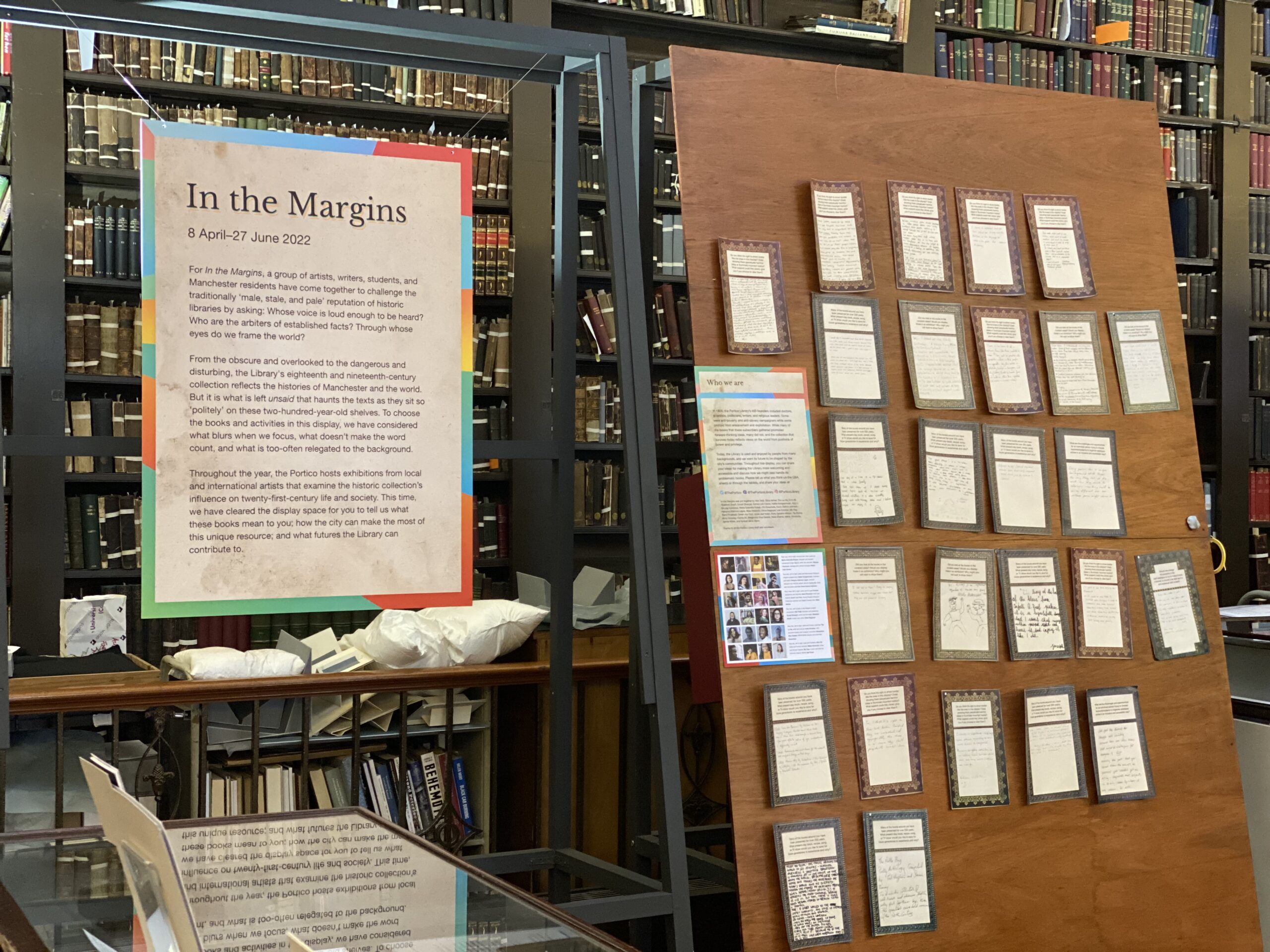

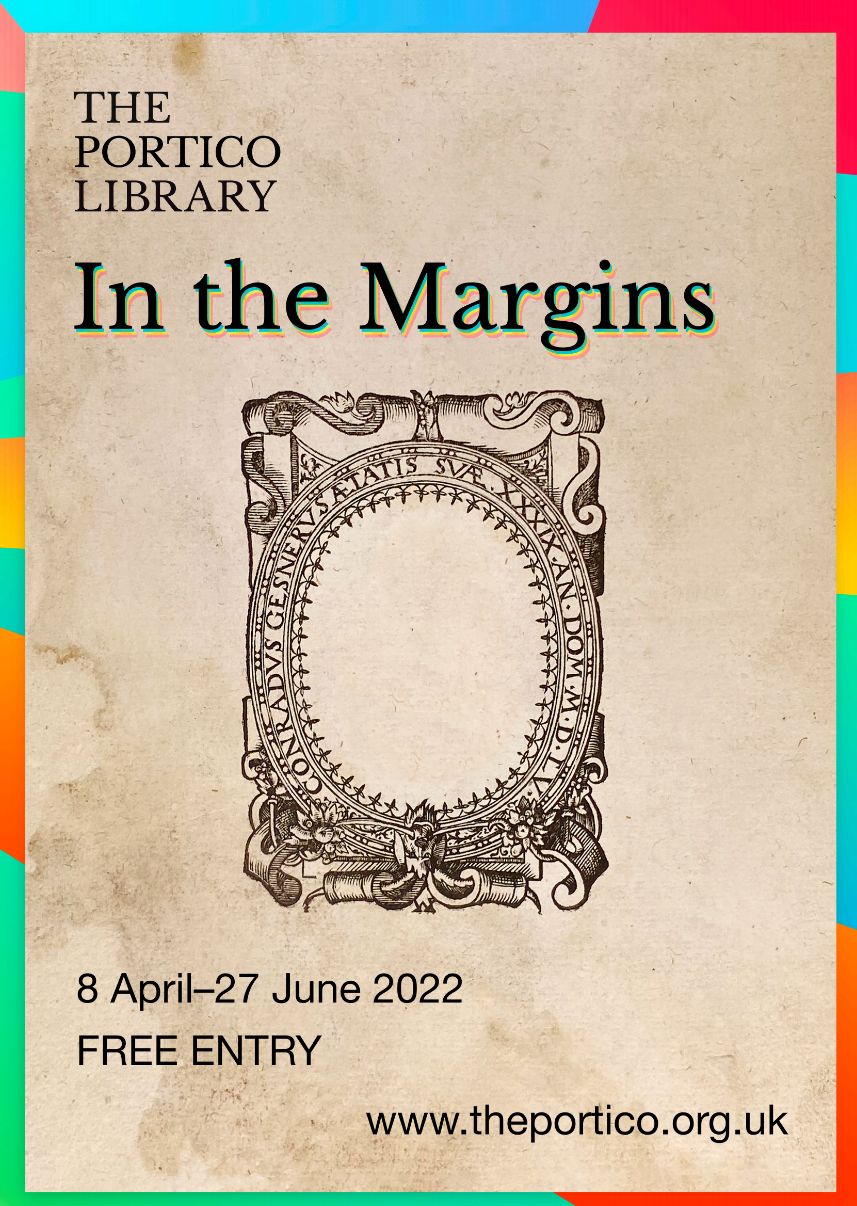

The Portico Library, hidden away in the centre of Manchester (right next to Manchester Art Gallery), is a 215-year-old institution holding over 25,000 books spanning a large variety of topics, themes, and eras. The library uses art to promote the library’s collection, to have conversations about the books, which take the form of workshops, talks, exhibitions and displays (one of which is open right now, named ‘In the Margins’)

With it’s beautiful regency-style architecture, stained glass, and wall to ceiling shelves of books, it’s easy to feel as if you have stepped into a dark academia Pinterest board. It’s free to enter, to explore (and to eat), so be sure to check it out whenever you’re next in town. However, there is a deeper history hidden in the shelves of this small Mancunian library. When it was first opened it was a membership basis only, which restricted poorer, working-class people and those whose first language may have not been English or been traditionally educated. Women couldn’t enter the library until 1870 and of the 25,000 books the majority were written by white, middle class, ‘Western’ men, even though the books in the library’s are of topics that span around the world. One of the best descriptions of the library I have heard, is that it’s like stepping into ‘the middle of a 19th century brain’.

As you can imagine, this leaves a skewed perspective of beliefs and morals in some which is being preserved in some books and illustrations within their collection. Ones that can be racially bias, sexist, ableist, homophobic…etc. But what do you do? Do you throw the books away? But if you throw them away, does that mean you’re denying responsibility?

This is what prompted me to speak to Apapat Jai-in Glynn and James Moss of the Portico library, to ask them how they are using art to change, but not erase, the narratives within their collection.

Apapat Jai-in Glynn, Engagement and Volunteer Coordinator.

James Moss, Exhibitions & Programmes Curator.

How does the Portico ensure multiple voices are present when encountering problematic works?

The Portico Library is a library and archive that utilises the expression of art to promote and deconstruct the books they have in their collection. They do this through direct artist collaboration and through providing access to art for everyone through holding workshops. This ensures everyone who they reach, can use art to freely express their own perspectives.

Through public programs, which consists of Off the Shelf articles on their website, public exhibitions, free workshops and more they can “select and invite more collaborators… to interpret the books”, as said by James. Interpret in a way they didn’t and couldn’t when the library was a ‘proprietary library’, where the Chairs of the library had full control of the way it was run.

It was their decision to make the library a ‘public resource’ and a ‘charity’ in late 2017, which has allowed them as staff and an institution as a whole to reach out and collaborate with other people. This has enabled them to, as James said: “decentralise… anyone in the library” and individually focus on the voices they wanted to collaborate with and boost. The library itself can now be used as a tool for exploration and promotion.

Why is art a medium you are using to explore the collections?

Apapat explained that the intentional use of art in the library setting, works as a more accessible “way to publicise the collection”, in a way that reading doesn’t. The act of reading requires you to be able to read the book first and foremost, it being in a language the reader understands to then comprehend the information. This hinders accessibility, whilst a visual exhibition allows multiple people to view at once. This ensures the work is more accessible, but also is a more fun and engaging for audiences, to view work and different perspectives in a “creative way and imaginative way”.

Using art to interrogate the contents of the books is a method the Portico uses to challenge historical biases.

What is the Portico Library doing to acknowledge and provide different narratives, particularly in terms of the sensitive and problematic contents in the collections?

James explains, why as a library, they believe it is important to engage with the community because “if you just left these books here without contextualisation or interpretation or attempt to interrogate them, that would be a political act in itself”.

If they are not interrogated, as an institution “you’re in danger of perpetuating” and validating the perspective of one individual, the author, or the artist and this is particularly important to interrogate when exploring sensitive topics, such as enslavement and racism.

It is an important part of the process for the library to facilitate this with the resources they have. As a library they are aware there is more to do, and they are actively engaging and supporting collaborations through community outreach. They have acknowledged they do not currently have a firm safety and support foundation, due to funding, but they are engaging with diversity and equity training, have a public program committee that exhibitions and ideas must run through, meaning they are reducing the risk of recycling the same viewpoints.

However, when speaking about inclusion within the arts there must be conscious awareness of ‘tokenism’, where a minoritized person or one perspective becomes representative of a whole group of people, because they are the only one to exist in that space. This erases the perspectives of other people who intersect that identity. To ensure tokenism does not occur, there must be a conscious effort to ensure multiple voices of people of various subgroups and identities are amplified.

As said by Apapat, they will not and “can’t force anyone to handle… difficult books” as they need to “willingly do it themselves”, particularly when dealing with artists and collaborators who are directly affected by the contents of a collection or whose heritage, culture or ancestors have been affected.

The aim of the library is to “provide a balance of creating as much… autonomy and agency and freedom for those artists, as you can”, which James acknowledges comes with “many interlocking steps”, which they are dedicated to continually put in place.

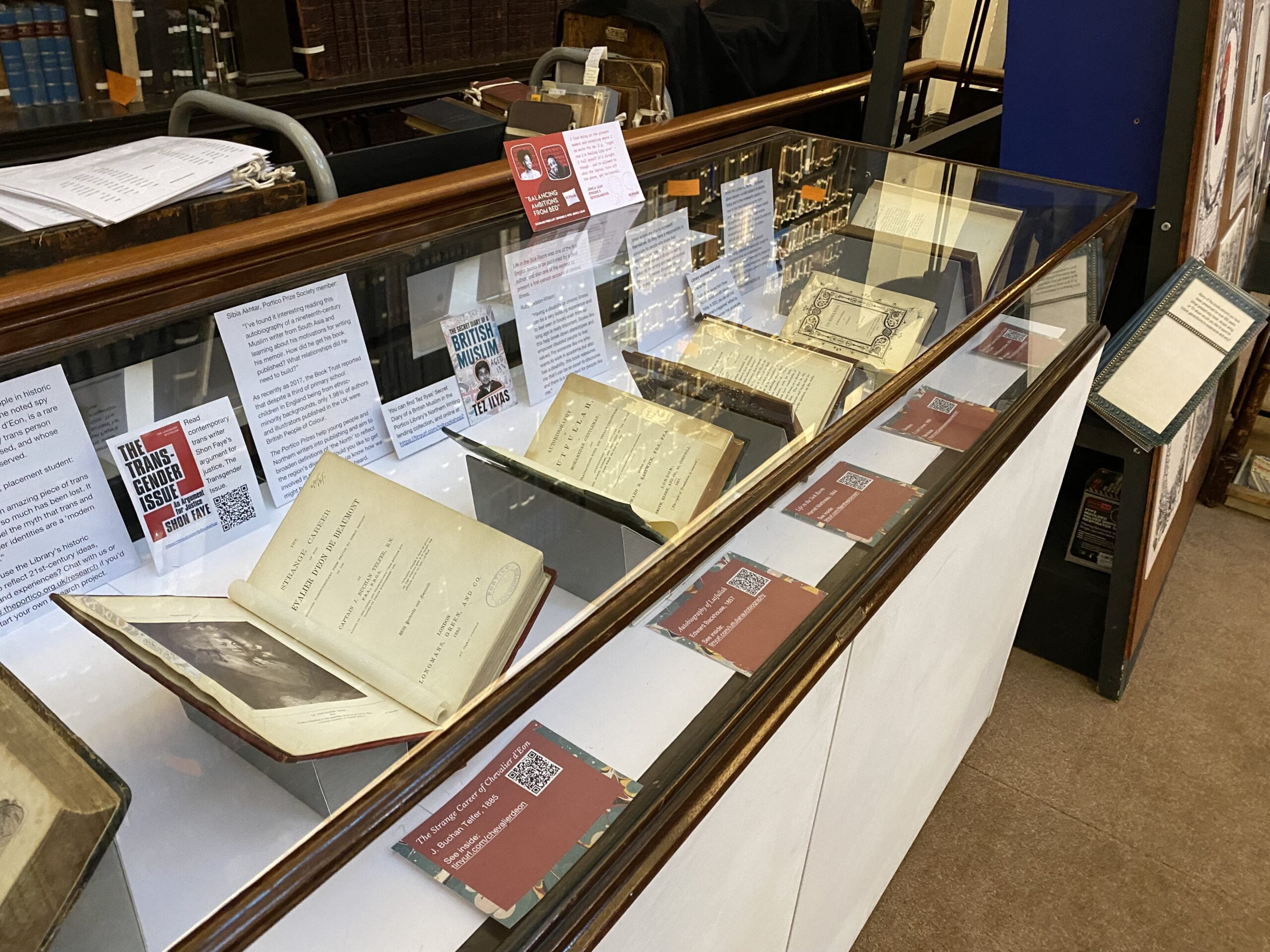

One of the ways the library is dedicated to acknowledging and not erasing some of the narratives present in their collection, is through art and exhibitions, which not only promote the collection but also create a community and a conversation about the books. It allows the collection to be accessible to more people, as the public can visually interpret a collection of books and interpret it themselves. It is opening the collection up in a way that has never been done before, rather than this information and history being gatekept in the walls of the library.

It is particularly important for people who have had their voices silenced or glazed over to take back control of their narrative and The Portico Library are taking steady steps to ensure this. There is a long way to go, but you’ve got to start somewhere, right?

***

From the 8th April-27th June 2022, there is a new display at the Portico Library named ‘In the Margins’, which displays and explores books from the collection. It’s free to enter, so if you’re in the centre of Manchester, press the buzzer by the door, go on up and have a look around.

Follow the library here, on their instagram and check out their website for more information.

Filed under: Community

Tagged with: art, books, colonialism, deconstruct, exhibition, interview, library, manchester, narrative, problematic, regency

Comments