Xavier Badosa from https://www.flickr.com/photos/badosa/9485872031

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

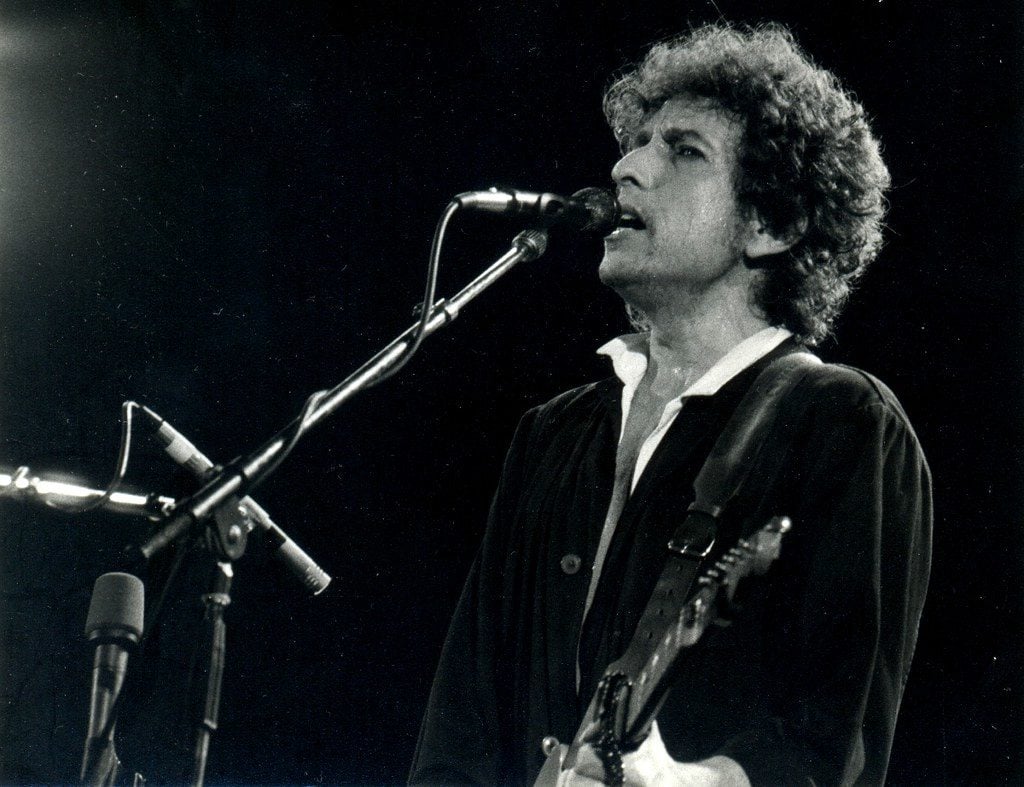

Michael Sutton shares the findings of his research on the complicated nature of Bob Dylan’s writing and what we can learn from it about literature as a whole.

Every narrative is fractured before it begins. No writer can encapsulate every aspect of a story. There will always be gaps. Things have to be left out. Some writers embrace this inherent reality of storytelling and look for ways to further fracture and distort their work. Bob Dylan is one of these writers.

Throughout his sixty year career, Dylan has blended standard storytelling devices with experimental techniques to shatter the narratives of his many stories, from his song lyrics to prose. This radical approach to storytelling is one of the reasons Dylan is considered by many to be one of the greatest literary figures of the last century, affirmed in 2016 when Dylan received the Nobel Prize in Literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”.

It is perhaps surprising that Dylan landed on this experimental style considering his initial influences, such as folk and country singers like Hank Williams and Woody Guthrie whose lyrics are beautifully crafted, though far from avant-garde. However, Dylan came to prominence in the 1960s, a time of great artistic experimentation and psychedelic surrealism. Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs are just a few of the poets Dylan recalls coming across and being influenced by in the early 60s. All of these poets make use of radical collage techniques in their writing, and this is a form of experimentation Dylan came to use freely over the decade in albums like ‘Bringing It All Back Home’ and ‘Highway 61 Revisited’.

This collaging is not only evident in Dylan’s song lyrics, but also in his first literary publication, the Burroughs-esque ‘Tarantula’, described by Neil McCormick as an “unreadable amphetamine-fuelled stream of consciousness blank poetic opus”. ‘Tarantula’ is certainly a bizarre and chaotic work. You can open the book to any page and find a passage of laugh-out-loud absurdity. The writing is so weird that Dylan was awarded the number one spot in the “Top Five Unintelligible Sentences From Books Written by Rock Stars” in the April 2003 edition of Spin magazine for the phrase: “Now’s not the time to get silly, so wear your big boots and jump on the garbage clowns”. I would contest that this is just the tip of the iceberg of ‘Tarantula’’s absurdism, where the fracturing of character and narrative verges on schizophrenic..

Dylan continued to use these techniques sporadically throughout his career, and this narrative fragmentation surfaced again in 2004 with the release of Dylan’s memoir, ‘Chronicles: Volume One’. The first thing to mention about ‘Chronicles’ is that, for what is supposed to be a biographical work, it is largely fictional. Since the very beginning of his career Dylan has been distorting the narrative of his own life. In his earliest interviews he claims that he gave up school to join a travelling carnival, among many other fabrications. He continued to make up stories about himself throughout his career, and in doing so he created a bewildering mythos out of his own existence. This mythos became even more entangled with the release of ‘Chronicles’, with many scholars, including noted Dylan biographer Clinton Heylin, claiming that the book has very little basis in reality.

Dylan is not only intent on fracturing his own narratives, but also the meta-narrative of literature that has developed over millennia. One of the defining characteristics of Dylan’s writing is its intertextuality, which includes him often inserting characters and themes from a vast array of literary sources into his work, from the ‘Bible to Moby Dick’. This proclivity for appropriation seems to stem from the folk and blues tradition in which his art is deeply rooted. But ‘Chronicles’ takes this feature of Dylan’s writing to an impulsive extreme, with some researchers stating they have ‘uncovered more than 1,000 items lifted from other authors’ in ‘Chronicles’ alone.

Appropriation is a fundamental aspect of literature. As Jonathan Lethem states, ‘literature has always been a crucible in which familiar themes are continually recast’. But by so radically fragmenting his writing with the words and ideas of bygone authors, Dylan seems to be making a statement about the relationship between this immense ‘crucible’ and his own artistic consciousness, showing how each constantly reflects the other, shining a new light on Dylan’s famous statement, “I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours”.

This mirroring is highlighted in Dylan’s lecture for his receipt of the 2016 Nobel Prize, in which he frames his work between the pillars of Homer and Herman Melville, ending the lecture with Homer’s words, “sing in me, oh Muse, and through me tell the story”. It seems that this ‘Muse’ is not only Dylan’s personal life, but every work of art that has come before. This is the true and encompassing fracturing of Dylan’s work; not only that of facts, time and space, or a surrealist fracturing of consciousness, but a fracturing of the history of the written word to create a powerful and profound poetic synthesis.

Filed under: Written & Spoken Word

Tagged with: abstract, Bob Dylan, fragmentation, literature, lyrics, music, Nobel prize, poetry, writing

Comments