Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize 2014

July 5, 2015

One of the most overly used motifs when discussing portrait photography is to note the portrait’s Rembrandt-like qualities. It’s easy to see why the comparison is drawn; portraiture often relies upon the interplay between light and shadow, and with it the strange, subdued intimacy that exists between the observer and the subject. By referencing the figure many still view as the master of the portrait, the critic is able to both compliment and concisely detail why it is that they enjoy the work. It’s problematic, despite being cliched. Must we still look to the 17th Century for our artistic goals and values? Is photography at its most artful when it resembles painting? We demand a veneer, a distance; photographs that look like paintings that look like the real. We want verisimilitude, not reality.

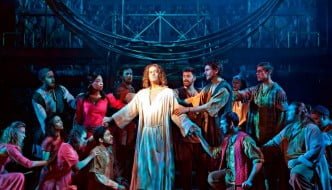

So when I read reviews of the “Rembrandt-esque” winner of the Taylor Wessing Prize, I was ready to be disappointed. Not that photographic portraits in that style aren’t beautiful – they often are – but because it almost represents a regression, a staleness, when the lead picture is an atmospherically lit close shot. All of this goes to show how wrong I was, and how short-sighted I was for building opinions of a work before I’d even seen it, purely due to a dislike of a slightly hackneyed art critic phrase. As soon as I saw David Titlow’s winning portrait, Konrad Lars Hastings Titlow, I loved it. The thing is, it does have a Rembrandt-like quality. But it’s so much more than that. It has an almost holy, biblical quality about it; beams of light illuminate the child’s face as he reaches forward to touch a dog that has likewise been lifted towards him. It is a depiction of innocence, and trust, and gentleness.

The second prize winner, a portrait from Jessica Fulford-Dobson’s series The Skate Girls of Kabul, instantly become my favourite. Vastly different to the Titlow’s winning portrait in both composition and subject matter, it combines an irresistible mix of feminism, young rebellion and vibrant colour. Fulford-Dobson’s portraits capture young girls learning to skateboard in Afghanistan, where it is illegal for women to ride bikes. The girl looks out at the observer, her steady, determined gaze framed by the rich blue of her clothing, her hand resting assuredly on her upright skateboard. She is immediately arresting, an image of calm confidence and quiet subversion, and I found myself drawn back to the portrait a number of times before I left the exhibition.

Jessica Fulford-Dobson © The Skate Girls of Kabul

Many of the non-placed entries are as alluring as the winners of the cash-prizes, with Karan Kumar Sachdev’s Vijay Rudanlalji Banspal a particular highlight. The portrait shows the eponymous guru, arms outstretched, grinning broadly, with softly glowing flood lamps lighting up the dusk. A sentence in the accompanying caption tells us he has sat on the chair meant for another subject in Sachdev’s ‘Yellow Chair Portraits’ series; the sheer exuberance of this spontaneous moment is what makes the photo so arresting, with the sunshine hued clothes Banspal is wearing highlighting the colour of the Sachdev’s chair. A more sombre, yet equally beautiful, piece is Graeme Robertson’s Blind Boy in Village Hut, which depicts Hamza, a young man who is blind and lives in a remote Ugandan village. The caption tells of his one wish: “that I will wake up and be back in school”. The portrait is deeply affecting; Hamza looks slightly away from the observer, his frayed t-shirt visible. We can do nothing, only observe. We know those in the portraits intimately, and yet not at all.

Vijay Rudanlalji Banspal © Karan Kumar Sachdev

One of the UK’s foremost photography prizes, the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize, has travelled from its home at the National Portrait Gallery to reside in Sheffield’s Millennium Gallery until Sunday 16th August.

Comments