Hellen van Meene, ‘Untitled (79), (2000)’

The late John Berger described obstacles faced by women in the arts thus: “men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Female form, he argued, appeared as a sugary, idealised object to be admired or consumed rather than understood. Writing in 1972, Berger’s theory paralleled a surge in feminist photography, which challenged status quo values that had for centuries rendered women’s views on women nigh on invisible.

It is the legacy of these criticisms on display in the all-female photography exhibition, Terrains of the Body, at the Whitechapel Gallery. The collection, lent by the National Museum of Women in the Arts (Washington, D.C.), showcases two-dozen works by seventeen artists from five continents who turn the camera on themselves. Reclaiming the body as a medium for expression, they each explore its personal and cultural associations to tell compelling stories that resonate with wider female experience.

To renegotiate historical representations of women many of the artists focus on the emotional states that arise at different points in a lifetime. Justine Kurland’s ‘Waterfall Mama Babies (2006)’ presents women with their children naked in a verdant environment in a scene that recalls classical paintings of nymphs cajoling in natural springs. Kurland’s women, however, attend to their children and do not indulge prying eyes of the viewer, instead immersed in joyous experience of motherhood.

Justine Kurland’s Waterfall Mama Babies (2006)

Framed opposite, Hellen van Meene’s portrait series delves deeper into the awkward, teenage gap between childhood freedoms and adult responsibilities, often unexplored in art history. Distant, enigmatic expressions complimented by soft, dreamlike exposures appear to let out a reflective sigh disassociated from the carefree attitude usually attached to young girls. Like Kurland’s photos, they present a narrative that wouldn’t fit between the tight parameters of male expectation that dominated prior centuries and still linger in popular culture today.

Further deconstructing canonical roles laid out for women within artwork, Marina Abramoviç presents herself in an equestrian portrait most commonly associated with valiant men. Astride a white stallion in an open Serbian landscape, the inimitable performance artist wields a white flag, her staunch pose infused with strength. Titled ‘The Hero (2001)’, Abramoviç’s portrait reimagines the conventions of heroism; woman replaces man and white flag, here a symbol of truce rather than surrender, restores harmony to land assaulted by war.

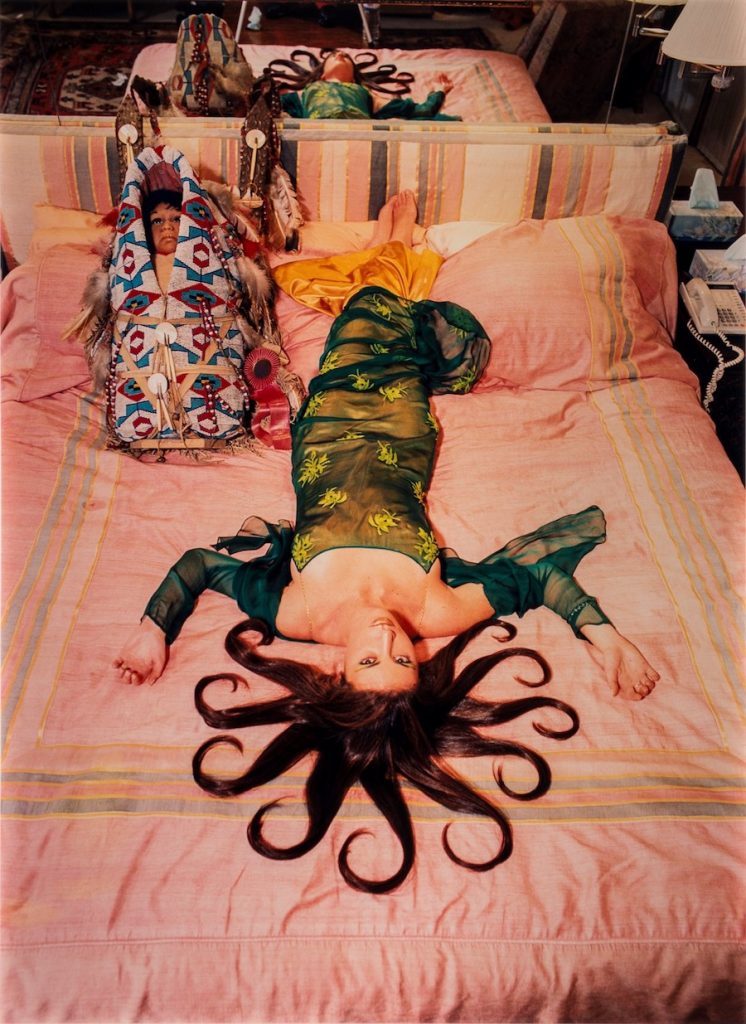

In many cases, whilst conveying the nuances of feminine experience, the artists successfully collapse boundaries between documentary and conceptual photography. The private moment of contemplation in Nan Goldin’s bedroom self-portrait is so tangible we forget her dual role of photographer and subject involved a construction of that moment. Others toy with conventions to create surreal encounters that set the viewer on guard. As a modern Medusa, Daniela Rossell adopts persona of the seductress, languid and writhing in a sumptuous interior. But, static from the neck up to keep her meticulously arranged hair coiled in place and her eyes locked onto ours, Rossell disrupts any opportunity to freely gaze upon her body. Sleek and evocative, her uncanny theatricality is douses the image in uncertainty. It feels at once posed and organic, not of this world.

Daniela Rossell’s ‘Medusa’

Playful manipulation is put to overtly critical purposes in the unmistakable symbolism of a caged woman silhouetted into anonymity in a still from Eva Sussman’s film ‘Rape of the Sabine Women (2005)’. Although only a momentary shot, the staging spectacularly captures the sense of confinement felt by women still searching for identity. Likewise, Kirsten Justesen’s ‘Portrait in cabinet with collection (2013)’ underscores feelings of powerlessness as the artist shelves herself alongside historical figurines to draw upon the absurd reductionism of female status to object. The simplicity of such imagery recalls work by their 1970s feminist predecessors, much of which is on show at Photographer’s Gallery, London, until 29th January.

The title ‘woman’ that connects the photographers at Whitechapel can be a difficult, uninvited categorisation, one many artists resist for fear it will impose an expectation of specific behavioural set, agenda, and attitude in readings of their work. Anchoring the exhibition, however, it dispels such ludicrous assumptions by affirming the world of women is complex, multifarious, and self-investigative. Traversing the lifestyles of various American subcultures in her ‘Project’ series, Nikki S. Lee adopts new personas with chameleon-like dexterity and provides insight into collective diversity. Collaborative duo MwanghiHutter’s panel piece ‘Shades of Skin’—four photographs that begin with the head and end on the feet, digitally mastered to darken skin tone in each respectively, that reveal scars across the body—asks us to consider an individual’s identity as capable of multidimensionality. By deconstructing the power for labels to be wholly defining, the exhibition invites a more fluid reflection upon self-definition, for both artist and viewer.

MwanghiHutter’s ‘Shades of Skin’

Needless to say, Terrains of the Body has opened during turbulent times. This weekend, an estimated 200,000 women marched on Washington D.C. protesting the inauguration of a President whose repeated, violent defamation of women did little damage to his reputation but has instead licensed misogynistic rhetoric and behaviour in society at large. It is clear that, to some, the female form is nevertheless a site to be exploited.

The work at Whitechapel may not directly address cultural oppression that motivated the earlier generation of feminist photographers, but this does not detract from its strength to challenge regressive values. The insurmountable sense of self, exhibited by every one of these artists in their ceaseless curiosity of the relationship between subject and medium, already defies any suppressive constructs that may arise with the new World Order. Woman as history has written her is a myth; her reality could never be narrowed beneath such a one-dimensional, umbrella identity. The female form may still be a territory hotly contested over, but it is one expanding and diversifying with such force that to conquer it is now impossible.

Filed under: Art & Photography

Comments