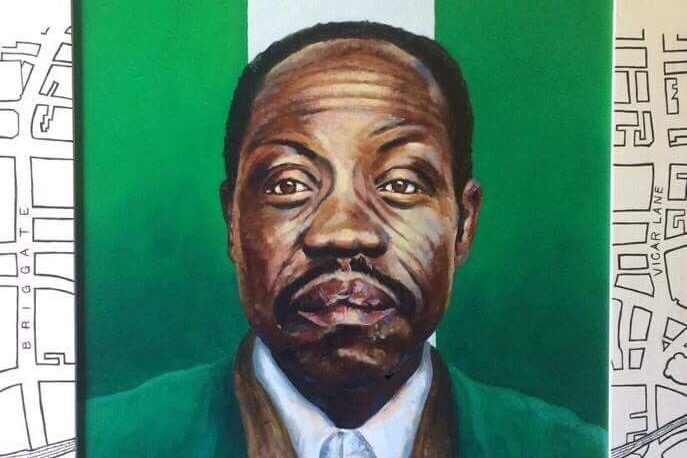

Credit: Lynne Arnison

Call Lane, a wide and meandering street in the heart of Leeds city centre, is a lattice of noise, lights, and smells. It is a patchwork of bars, restaurants, and clubs often spilling over with students tipsy from the ambiance radiating from the warm neon glow of the glass- fronted buildings. But, Call Lane and its characteristic red brick so steeped in the blissfully fuzzy alcohol drenched memories of many Leeds residents, is also the suspected setting of David Oluwale’s last moments on April 18th 1969.

David Oluwale, a British Nigerian man, came to Britain in August 1949 when he was likely 18 or 19; the same age as many who make the symbolic migration from home to University. However, Oluwale’s journey was different from the nervous car-ride pressed up against the window by duvets, pots and pans, and pillows. He arrived on the shores of Britain hiding on board a cargo ship destined for Hull. The British Nationality Act of 1948 meant that Oluwale and anyone else from the British Empire could settle as a citizen upon production of a British Travel Certificate. After spending 28 days in prison under the Merchant Shipping Act because he arrived in England as a stowaway, he travelled to Leeds as it is thought he knew people there.

A tailor by trade, Oluwale was nicknamed ‘yankee’ amongst his friends because of his love for American-style suits. Yet his future filled with sewing seams and hemming garments was not to be realised.

In 1953 Mr Oluwale had his first altercation with Leeds police. It is thought that he became involved in a fight and took a truncheon blow to the head. After going to jail he spent the next ten years in Menston Asylum, a psychiatric hospital, where he was given electric shock treatment and anti-psychotic tranquillisers. Upon release from Menston, Oluwale re-entered Leeds where, unable to hold down a job because of years of mental trauma, he became homeless.

It was during his time as a mentally vulnerable, homeless, poor Black man on the streets of Leeds that Inspector Geoffrey Ellerker and Sergeant Kenneth Kitching began to target him for two years. Beating him up, urinating on him, driving and dropping him forty-minutes away into the depths of Middleton Woods were just some of the ways in which Ellerker and Kitching tormented Oluwale. They made it their goal to humiliate, abuse, and eventually, according to witnesses, chase Oluwale to his death by drowning in the River Aire. His body, found two weeks later, had clearly been badly beaten. Later, he was buried in a paupers’ grave in Killingbeck cemetery with nine others.

The two police officers were, thanks to police cadet Gary Galvin who blew the whistle on what had happened, brought to trial in 1971 for the manslaughter of Oluwale. This was to be the first prosecution of British police for involvement in the death of a Black person. However, despite the charges against the two men, they were found only to be guilty of causing actual bodily harm with Ellerker receiving a sentence of 36 months and Kitching receiving 27 months. Race played little part in the trial despite the fact that Oluwale’s nationality was listed as “wog” on his charge sheet rather than “British”.

It could never actually be proved that it was Ellerker and Kitching who were the ones seen chasing Oluwale down Call Lane towards the Aire. Yet, in a way, the story of David Oluwale is not one about legalistic fact but the lived reality and legacy of his life as a Black, homeless man suffering from mental illness in post-war Britain.

The story of Mr Oluwale is symptomatic of the disease of negligence that permeated throughout post-war Britain with regards to Black colonial migrants who came to Britain. His life is one of being treated as the eternal ‘Other’; targeted in the first instance because he was Black and then because of his mental vulnerability and status as a homeless man.

Race, class, mental illness, and homelessness all intersect in Oluwale’s tragedy. All four facets are intertwined and reinforce each other leading to a complex spiderweb of systemic oppression and injustice.

Although today racism is less overt, there is less stigma attached to mental health, and there are avenues of help available to those sleeping on the streets, the legacy of this sticky and tangled web continues to cast a shadow over the present.

Credit: Max Farrar

—

I talked to Dr Max Farrar, Secretary to the Board of the David Oluwale Memorial Association and asked why Mr Oluwale’s story is still so important today: “Those issues from the 50s and 60s have only been partially addressed. There are rough sleepers everywhere in the city, though provision has improved. The huge psychiatric factory in which David was incarcerated has been closed down, but mental health services are overstretched. The police are less prejudiced, but mistakes are still made. Racism has changed its shape but is far from being eradicated.”

Why should those living in Leeds and around the country know about the story of David Oluwale? “If they care about the lives and traumas of ordinary people, if they care about racism, mental ill-health, destitution, rough-sleeping and police brutality, they should know about David Oluwale. His twenty years in Leeds exemplify all that was wrong in this city in the 1950s and 1960s — its failures in compassion and welfare, its ignorance of the role black people were playing in rebuilding the city, and its systematic racism.”

Since Oluwale’s death not a single police officer has been convicted over a Black person’s death in custody. Black people account for 8% of deaths in police custody whilst making up only 3% of the population. Whilst there should be no deaths in police custody, the disproportionality is nevertheless revealing. Between 2012 and 2017 statutory homelessness increased by 42% amongst Black households. With regards to mental illness, statistics show that Black African women are 7 times more likely to be detained than white British women under mental health legislation.

To understand the present injustices that continue to plague British society for Black people it is imperative to understand the past which created these deep inequalities.

So what more can the city of Leeds or those living in it do to remember and honour the name of David Oluwale? Dr Farrar said that “we have to redouble our efforts to combat all of David’s abjections that persist today, whether they are the result of discrimination based on a person’s class, colour or culture. Everyone, and every institution in the city can do more. In David’s name, the #RememberOluwale charity is building a Memory Garden in the city centre, near where he was drowned. It will feature a world-class sculpture, rising out of water, symbolising hope, joy and social progress. It will be a playful place, regularly animated by performance, music and spoken word, where people from every ethnic group will gather, eat together and converse. Everyone in Leeds and beyond is invited to contribute to this project, honouring this man whom history was about to forget, in pursuit of our common humanity.”

Finally, I asked if the recent reigniting of the Black Lives Matter protests will help bring attention to past injustices such as the death of David Oluwale: “In 2015 we supported the Black Lives Matter Ferguson tour of the UK and we fully support the May-June 2020 protests. There is a thirst among people of all ages and all colours to re-examine British history through the lens of slavery, racism and oppression. Because of the abhorrent killings in the USA we in the UK have been forced to note the over-representation of black people who have died at the hands of the British police over the past 50 years. This is a terrible history, but it has to be faced if we are to make progress.”

David Oluwale is both the victim and the product of a society and a city which failed him. His life may have ended in 1969 but his legacy must endure. Police brutality against Black people continues to endure in Britain as do the other systemic forms of discrimination that Oluwale faced. His name and life should act as a reminder of past sins and an admonition that much more is left to do.

Filed under: Community

Tagged with: Board of the David Oluwale Memorial Association, British, brutality, David Oluwale, homelessness, leeds, legacy, negligence, nigerian, police, race, Racism

Comments