University of Chicago Press, 2020, based on graphic by Hanna Rose Shell.

You may already know what ‘shoddy’ is, or perhaps you use the word to describe a badly done job, like hanging a shelf that can fall down at any second. But there is a whole other meaning to shoddy, and one that, to Hanna Rose Shell, has opened up a whole new world of textile history and research.

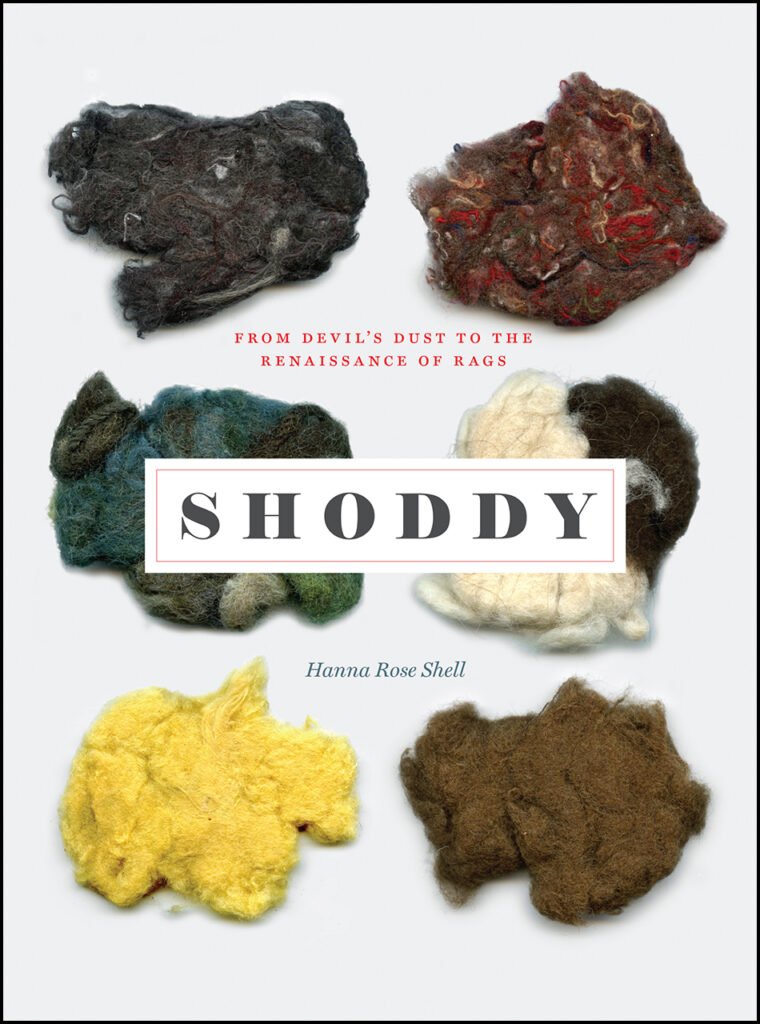

Hanna has recently published the book ‘Shoddy: From Devil’s Dust to the Renaissance of Rags’, which I found out about through a friend who knows I love anything related to textiles. We quickly got in touch, worked out the time difference (Hanna is based in Colorado) and eventually sat down for a lovely, long Zoom conversation about what led her to ‘shoddy’ and kept her there for the last few years.

Shoddy is the method in which “recycled wool, or more specifically wool that made it into clothing, worn for years and tossed when threadbare, was resurrected and sometimes along with wool fresh from the sheep, spun into new cloth” with the use of machines called the ‘devils’.

Self-described as “a historian of science, technology, and art technology as well as a filmmaker”, Hanna’s interest in textiles started early: “I always loved second-hand clothing: going to thrift stores with my dad was a big thing. But in 2002 I got really interested in talking to people at second-hand stores, hearing their stories about what had brought them there. I teamed up with a great friend and collaborator of mine, Vanessa Bertozzi, and we started making an experimental documentary film. At that time, my interest, and the film project that came out of it, was pretty unusual. In fact, I proposed the subject as my dissertation, since I was in grad school at the time, but it was considered too unusual a project.”

Photo by Hanna Rose Shell, Petionville, Haiti

Then came a film, made with Vanessa Bertozzi about the flow of second-hand clothing between the US and Haiti, focusing on globalisation and immigrants, and what that meant for them socially and culturally. ‘Secondhand [Pèpè]’ was a big project that we finished in 2007. The film played at film festivals, museums and galleries. While I was doing the research for it, I came across this term shoddy. I came upon a newspaper article about uniforms made of “shoddy” that were mass-produced during the first world war.I was really transfixed by the word shoddy and what seemed to me at the time a very unusual usage. I had grown up thinking about “shoddy” only in terms of it being an adjective meaning “badly done,” but here it was as a noun. From there, I did the preliminary research, and learned of its origins in the textile industry in West Yorkshire.”

That may have been the first lightbulb moment but it took Hanna a while to come back to the concept of shoddy, once she finished her dissertation, as well as the book that grew out of it, titled ‘Hide and Seek’, about the history and theory of camouflage. “As soon as ‘Hide and Seek’ was done, I decided to take a trip from Boston, where I lived at the time, to West Yorkshire. I just showed up and as soon as I did I started to meet people.”

I asked Hanna how she knew who to talk to, because despite Yorkshire having been the textile centre of the country, this still seemed like a niche topic. “I read about a local historian from Batley named Malcolm in an article online and then I looked up his phone number. He met me at the train station, and showed me around; his enthusiasm was incredible. After that I just started showing up at places, like at a textile shredding company. I think a lot of people were interested in the topic and were happy that I was interested in it too, and in who they are. They were pretty open and even gave me bits of textiles. I spent a little time at the archives in West Yorkshire, but also did a huge amount of research based in the United States.”

Photo by Allegra Boverman

The initial idea after Hanna’s trip was to make a film but this morphed into a book project due, in part, to the fact of her professorship, and its requirement for her to publish a second book. “In the end, I think the book format actually ended up being really ideal. In it, I tell three different stories about shoddy – I call them “Acts” with the titles “Devil’s Dust,” “Textile Skin” and “Lively Things” – and it would’ve been hard to make these work together as effectively in a single channel film format.”

The book focuses on the beginnings of the shoddy industry, its role in army uniforms, war photography and war more generally, the question of cleanliness, ‘miasma’ and disinfection in relation to textiles, and the potential future of shoddy in our contemporary world.

“Right now because the book is out and I have the freedom to make art, I do think a lot about doing that. I wanted to spend last summer in England both talking about my book and going back to West Yorkshire. I had wanted to do some more filming and ideally to organise screenings or events in Leeds, Bradford and the surrounding region. But then, of course, the pandemic happened. It’s still not clear when I’ll be able to come, but I’m hopeful for summer 2022. I’m hoping to do some in-person book readings, events and some artworks. Zoom just doesn’t work for me.”

Photo by Hanna Rose Shell, West Yorkshire

It’s interesting talking about a textile material, which by its very nature is tactile and has all of these identifying qualities like smell, weight, colour, without actually handling it. The chances are we’ve all actually seen, touched and used shoddy at some point in our lives, but I asked Hanna to tell me more about it – there is something fascinating about describing tactile qualities over a Zoom call. What’s the material when you handle it, what does it feel like?

“There are all different kinds of shoddy, I’d say that handling them is really different. One kind involves at least some level of waste wool so when that’s first being made, it can be kinda oily, dirty and smelly, it smells like wool. But other types of shoddy can be really powdery, or as a material can feel really fluffy.”

“You can see that on the cover of the book, these are all different kinds of shoddy materials that are more traditional. Old kevlar and bulletproof vests, that feels a bit like fibreglass. Then there is khaki, army cloth that feels like wool. But shoddy clothing which traditionally was old boiled wool, army coats, British navy coats, army blankets – that just feels kind of rough.”

Hanna’s book looks at many historical examples of shoddy use and we can see why at the time this may have been seen as the best way of ‘recycling’ old textiles. But the key question is: is shoddy still being used now?

“Shoddy is used in all sorts of interesting applications, for example carpet padding, or mattress stuffing. A lot of mattresses are stuffed with shoddy material, so in Yorkshire there is a big bedding industry. Even though the wool is gone and England’s got some post industrial issues, there’s this bedding industry and the processing of second hand clothing industry, and a lot of that second hand material goes into mattresses. Which is kind of gross actually.”

Photo by Hanna Rose Shell, West Yorkshire

This is something I’d been wondering about since we began our conversation, perhaps partly induced by the need to disinfect and clean inspired by our current circumstances – did anybody clean shoddy, or was it just left dirty? Would someone just sleep on a mattress filled with dirty second-hand material? “This is a huge fascinating question. There was always this concern about second-hand clothing and shoddy – not just about whether or not it had germs, but did it have the spirit of dead people?”

“Even before people knew about germs there was already this question, because a lot of the people who give up old clothes are dead, so were there bad spirits in it? Germ-based theories of disease developed and spread starting in the 1850s and through the 1870s and 80s. Rags generally, and the shoddy industry specifically, became part of the larger debates about whether it was true that disease was caused by germs, transmitted by so-called ‘fomites’. Clothes and fabric were seen as possibly a hugely important class of fomites. There were big debates about it, and whether clothing can carry germs or transmit disease. It finally became clear that germs can live on clothing, there were questions about how you disinfect it, and people would pretend that they kinda disinfected it. You could cook it, or maybe people thought you just heat it up and shred it.”

“I still think about it all the time: when you’re dealing with a really low value good, most of the second hand clothes are low value things that can’t be sold in another way, but you have to put a lot of effort into disinfecting it. A lot of people would claim they did, and especially if it’s stuffed inside a mattress, who’s going to check it? Are you gonna cut open your mattress to smell it?”

“There was a lot of concern about how to regulate it. In England one of the seminal, important moments for this question of disinfection was during the cholera epidemics in Exeter in the 1830s, and then London in the 1850s. The state started confiscating clothing from everybody who was sick. And so people would burn it, there were these big burn rituals.”

The concept of burning sick people’s clothing in the form of a ritual doesn’t seem too unlike burning witches. “That’s exactly right, there’s something very witchy about it. With shoddy in general, in a way it’s just this very base material but it’s actually really uncanny and witchy. People have worn these clothes and they have all their sweat, all their crude life, and then… they get remade.”

Photo by Hanna Rose Shell, West Yorkshire

“This question about disinfection is very interesting. In the US there’s a big Goodwill industry, and I’ve been to these sorting facilities and asked: ‘Do you sterilise these clothes?’ And they’d always say ‘Yes, of course we clean them, they’re very well cleaned before we put them back on the shelf!’ I took tours and never saw where that happened, but I didn’t wanna press too much. How do they clean them? And if they are collecting second-hand clothing, and selling the t-shirts for 50 cents, where would they find the money?”

It seems ironic then that high street shops have ‘recycled’ ranges or eco clothing lines which are so much more expensive than the brand new ones. “Yeah! That all started in the last 5 years in all of the high street shops like H&M and Zara. Until a few years ago they weren’t really getting that much pressure, it was a marketing idea. These clothes are more expensive and more prestigious because you’re buying into a political statement. It’s a class issue too, by buying it you’re supporting some kind of good cause and a sense of comfort that you’re doing something good for the planet. Realistically though you’re just giving money to H&M.”

Hanna says that she’d love to turn the results of her research on shoddy into an installation, although “other people could see it as political. Saving the world is hard, and I think shoddy in and of itself is fascinating without that aspect.”

Moving on, I asked Hanna what’s been the most surprising thing she learned during her research was? “I think that I really found it surprising that my inquiry that began with learning the etymology of the word “shoddy” provided an entry, a portal, into an amazing world, and a totally unique way of connecting so many different aspects of history and culture. I think that was really surprising that it could connect so much, including so many things I haven’t even explored yet.”

The other surprising thing and something that Hanna would love to do a project about is shoddy weeds. “I found all of these people in West Yorkshire who were really fascinated by shoddy weeds: they’re seeds that came in from foreign countries that would come in on the fleeces of sheep. They would get processed out and become the waste that would end up in shoddy heaps.” [Shoddy heaps are quite literally what they sound like – heaps of dusty waste material, left on the edges of fields, waiting to be used as fertiliser – take a look at the photo below.] There is a whole group of people who seek out and collect the weeds, like a lady that Hanna found in Scotland, who has collected and preserved shoddy weeds from the early 1900s. They go out to the shoddy heaps and look for them every spring. “There’s this issue of post-industrial decline in England and the nostalgia for the textile industry becomes wrapped up in these shoddy weeds. The wool on the heap itself is covered in so many preservatives and disinfectants that the seeds are killed, so all of this was fascinating to me.”

Photo by Hanna Rose Shell, West Yorkshire

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, can shoddy have a future? Does the idea and process have any way of surviving in our current times of excess? Could we perhaps find new uses for it?

Hanna thinks “it can be used as a metaphor that is a really useful way to apply to lots of industries and material processes that allow for the regeneration of waste. I think that’s its future, although this may just be wishful thinking. If my book takes off and everyone gets on board with my idea that shoddy, as a thing, as a process, and as metaphor, is super rich.”

“In general, once shoddy is not just about wool but all textiles, I do think it has a bright future. It can be used for insulation and recently it seems that textile reuse and ideas of mending and repair seem really prevalent in the art world. There are a lot of artists and craft fashion designers working with it. There may be a way to do it in such a way that it’s cost effective, so it’s not this prestigious fashion. And maybe eventually it will become a way for people to get dressed.” I like that idea, it’s tangible rather than just a floating ideology. “Shoddy’s history is not about ideology and environmentalism but is actually about the nuts and bolts of how to make the economy work and how to get dressed. It was based on this really capitalist idea of ‘let’s find a way to make money off the waste product and not just throw it away.’”

“But my real, optimistic hope is that shoddy itself, as well as the concept of shoddy and its unique history can inspire us as we all work together to frame a movement towards a sustainable future, both in relation to the fashion and clothing industries and more broadly.” Let’s hope it can and that we can remake our future on this planet with its help, even if just a little bit.

You can buy Hanna Rose Shell’s book ‘Shoddy: From Devil’s Dust to the Renaissance of Rags’ here and learn more about her research.

Comments