The Long Read: “Speaking to the people” – interview with Joe Nice

Transatlantic Dubstep pioneer Joe Nice talks with Theo Freedman about building coalitions, confronting racism, sound system culture, and ripping UK Garage Dubplates from AOL Messenger.

The effervescence of Joe Nice is the first thing that you cannot leave unnoticed. As soon as we logged on to our call, Joe was visibly bubbling with anticipation as he expressed his excitement at an opportunity to “share with the people” which he maintains is “a wonderful thing to do”. His lucid, incisive provocations and discussions were interspersed with his frequent proclamation that he was “thoroughly enjoying” being able to have the opportunity to have a free-flowing discussion where no subject was off-limits.

Over the period of our almost 140 minute call (too apt and poetic to be deliberate), we covered the rewriting of the US Constitution, the oral history of FWD>>, Fred Hampton, the relative melancholia and beauty of Sade and Billie Holiday’s voices, austerity, and more. For a man largely responsible for the export of Dubstep to North America, Joe’s humility is entirely sincere, manifesting as thoughtful engagement with my questions and never once erring into the twin dangers of contrived false modesty or arrogance, a pitfall which many in dance music circles fall afoul.

We began our conversation in Baltimore, the city where Joe’s inimitable tenacity for new, interesting music was so efficiently developed. “My first love”, Joe says with an earnestness that really does communicate ‘love’, “was Baltimore Club and Soulful House. I still listen to Masters at Work, Todd Terry, Blaze, Josh Milan… there’s something about it that’s never left me. But in 1998, a friend brought over a UK Garage CD and I just thought “Wow, this is fresh!”. We’re talking MJ Cole, Mike ‘Ruffcut’ Lloyd, Norris ‘The Boss’ Windross, DJ Luck & MC Neat. You know? Proper UKG!”

It was at this point that Joe revealed to me that it was this wave of UK music that actually cut his DJing sabbatical short and got him back in the booths, forums, and record shops. Much like Joe’s interest and understanding of important transatlantic connections and collaborations in regards to building broad, “multi-racial” coalitions, taking on global capitalism, and fighting racism in the UK and US – so too, it was his engagement with the low-end frequencies of Croydon, Norwood, Brixton, and Transition Studios that played a vital role in his reinvigorating of the Baltimore music community.

When discussing this global transfer and exchange of cultural innovations, we go on to focus on the power of music to unite people across borders and provide grounding in harsh economic and political times but before doing so we touch on the amusing, frivolous anecdotes that really encapsulate the organic nature of Dubstep and Grime. “We’re talking AOL Messenger, yeah that old! It would take me 2 hours to get a tune sent over on dial-up broadband from the UK… which I then cut on to dubplate so I could play them out”. Here he touches on a really significant turning point in June 2002 in the Invasion tent at Starscape festival where “Hatcha played a 1 hour set, 45 minutes of which purely on 10 inch dubplates. And he’s rinsing out tunes! He was going deep! And I stood there thinking: what on earth am I listening to?” This is just one of a smattering of key moments in that early noughties sweet spot that evidently inspired Joe to build and maintain such strong bridges with the burgeoning dance music scene seeping through from the subterranean underworld of South East London.

And that inimitable, murky London sound becomes a real sticking point in our conversation. It is clearly evident that Joe Nice has a deep political understanding of subcultural phenomenons. Despite living in Baltimore during these years, he freely admits that the specifically UK sound of Dubstep – mirroring the backfiring car engines and sirens of London via the bone-jangling sound systems of Leeds West Indian Centre, the DMZ all-nighter parties at St. Matthew’s church in Brixton, and the FWD>> parties at Plastic People in Shoreditch intertwined with the patois drawl of many thousand diasporic African-Carribeans – reflects the never-ending clash and conflict between social classes, demographics and stratifications in London and compares them to similar fractures in American cities during the Golden Age(s) of Hip Hop.

Careful not to fall into what he identifies as a “romanticism” or an overly nostalgic view of musicology, when asked if it felt momentous being so utterly central during the fever pitch of FWD-era Dubstep, he clearly communicates that at the time it was just a case of going to “play records with friends, maybe have a few drinks” and that the realisation of the epoch’s massive significance for ears to come was there as a subtle backdrop but that in the moment it was less ceremonial and more casual than that. These sentiments are echoed by the recently unearthed Kode9 footage of Mary Anne Hobbes’ historic Dubstep Wars event in which the jovial, relaxed atmosphere between a group of friends is plain to see.

Moving sideways from Dubstep to delve into Grime, I propose to Joe that “Grime really is a product of grotesque inequality and grotesque poverty” but that even then, prospects for young people in the UK and US were better than they are now. Those same youth centres that gave life to the bubbling, vivacious Grime MCing scene of East London have now been cut to shreds by successive neoliberal governments. A grim vision sadly modelled stateside where wages continue to stagnate amongst rising living costs for American youth, disproportionately from BIPOC communities.

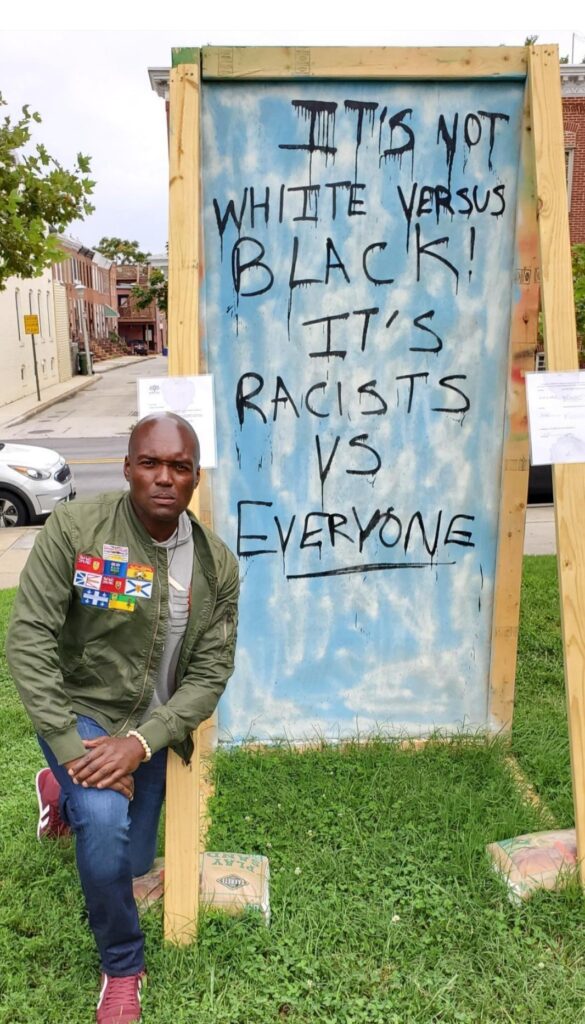

We turn our focus to current affairs in the US where Joe speaks of the need to move away from a political culture defined by war and neoliberalism as catalysed by Bush, Obama, Hillary and Bill Clinton, he adds acerbically that “Bill Clinton was the first Democratic president to ‘out-Republican’ the Republicans”. This clear understanding of what Joe calls the “duopoly” of US politics in Washington that we must deviate from and use as motivation to build a better model of democractic, economic, and sociopolitical power. Citing Bolivian truck drivers, the Gilet Jaune and Gilet Noir movements in France (and in an effort to raise awareness and show support, Joe wears a yellow vest on Saturday shows), British trade unionists, and the ever-hopeful but sadly vain Bernie Sanders’ campaigns as flashpoints; Joe seems to comprehend that a groundswell of public antipathy towards this rapacious global politics exists and that in order to harness it towards gaining political power we must “take control of our communities by having conversations outside of our social circles, discover agreements with those other people, popularise the agreements, and enforce the agreements with policy. Joe exclaims that we must “stand up for our brothers and sisters”. These are rousing words that come from Joe’s demonstrable record of activism and community engagement in racial justice and workers’ rights struggles but are not merely tangentially related to the way he views music and its power.

Certainly the spirit of solidarity and cultural exchange is central to his tireless work ethic in importing UK dance music and making connections across borders to enhance the global listenership of primarily working class, underrepresented, and BIPOC voices. Moreover, the way he talks of music as a unifying force from the “melancholia of Sade” and the “talent of Prince which you simply cannot deny” is built upon a non-written but inalienable commitment to democratised music and culture for all as a soundtrack and enabling tool alongside emancipatory politics.

When asked how he felt whilst witnessing the January 6 scene of Trump supporters storming the capitol he told me earnestly: “anger, disappointment, shame. Angry with the inequalities with which the police handled the situation.” Here Joe’s real political vision is borne out. Rather than falling into the trap of liberal hand-wringing and the kneejerk defence of American liberal democracy which he objects to in its role apparent as “judge, jury and executioner in the law of morality”, Joe immediately frames the Capitol events in the language of police oppression and racial justice. He compares the soft treatment of law enforcement towards largely White Republicans with the brutal, racialised state murder of thousands of Black, indigenous, and people of colour across the country. In order to address this divide, amongst others, I am told we need a “cultural autopsy of all the institutions of American life” and a “re-writing of the US Constitution” towards a bill of rights that actually reflects matters of racial, economic, and social justice such as reparations for American Descendants of Enslaved Africans, demilitarised police forces, nationalised healthcare, and tangible coalition-building, and political education on the exploitation of minorities in the states.

We compare notes on the glaring inequalities that many Britons face along different but related lines and conclude that a great deal of private capital and media bylines have gone into obscuring the fact that “poor Black folks and poor White folks have a great deal in common ”. Something that Joe tells me “Fred Hampton understood”. Here I raised examples of working class solidarity across lines of identity such as Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) where certain socially conservative elements in mining communities were brought on-side to LGBT liberation in response to the tangible support they received on picket lines from young LGBT activists with whom they would otherwise not interact. At this juncture Joe tells me that to create a “rainbow coalition” of working people, we are going to have to build those coalitions with people who we disagree with, understand their concerns and use them to strengthen our movement. Whilst vehemently opposed to his presidency, Joe freely concedes that Trump was a break from the norm and even cites his opposition to certain neoliberal trading policies such as NAFTA on protectionist grounds as reasons for his working class supporter base that any useful left wing political project must confront and engage with.

Joe Nice is a man dead set on building bridges and coalitions and being part of political change and this is possible due to his solid comprehension of material concerns of working class people be they in Baltimore, Beijing, Brixton, or Bogota. Even a brief glance at his contribution to both UK and US music and culture will tell you that his attitude toward music and its unifying power is inextricably linked to his view of the world and his desire to build a better one in the decaying ruins of neoliberalism. If Joe didn’t play music, the world would still be blessed by his political existence and if his political life was not significant, his music would still be deeply important. Somehow, when the two converge; we get an insight into an incredibly talented and ambitious empath who, whether via his epic Instagram politics videos or his dulcet tones on Sub FM, I hope will never tire of “speaking to the people”.

Comments