On The Power of Images – a series

February 13, 2016

Here in the domain of film and TV, it is often easy to get caught up in an endless cycle of previews and reviews. However, one of our writer’s, Loïs Soleil, has offered an exciting, unique suggestion on how else we can utilise this platform. When Loïs sent in a fifteen page essay on the relationship between Hollywood cinema and 20th century advertising, it was initially difficult to see how it might slot in amongst the other content already up on the site. However, upon reading, it appears that the perspective offered is exactly what we need. Rather than feature pieces focusing on specific films or programmes, we are endeavouring to branch out and get some broader pieces of writing up on the site.

I present to you all the birth of the first ‘episode’ – a taster if you will – of Loïs’ essay on the representation of women in popular culture. To keep you on your toes, we will be releasing one every week.

The Power of Images by Loïs Soleil

This paper focuses on Classical Hollywood cinema (1917-1960) and twentieth century advertising. Its intention is to discuss how woman are represented and contemplated in popular culture and how this depicts the patriarchal context of the creation of these images. We will analyse the ‘male gaze’ laid upon the female figure as well as the concept of the ‘ideal women’ and discuss subsequently the gender positions created for the viewer (showing ‘woman as image’ and ‘man as bearer of the look’), as well as repercussion of the male gaze on: how women view themselves, and how they act in society. I will therefore draw a parallel between Laura Mulvey’s theory of the gaze in Classical Hollywood cinema and Jean Kilbourne’s speech at Cambridge on the established image of the ‘ideal women’ as a result of the powerful influence of the advertising industry.

“The first meaning of fascination is to “bewitch, enchant”.

‘To fascinate is to bring under a spell, as by the power of the eye; to enchant and to charm are to bring under a spell by some more subtle and mysterious power’. [Century Dictionary]”

The power of cinema lies in its delivery. Barthes explains our fascination for film and the magic of “cinematographic hypnosis” (the lose of self in the image). The ‘anonymously populated’ ‘darkness of the theatre’ (which disconnects the viewers from each other), the ‘inoccupation of the bodies’ as the ‘gleaming vibrations’ of the screen creates a hypnotic effect on the observer that entices him or her to listen and strengthens his/her attention to the implicit message of the moving images whilst still keeping him/her in a vague daze (not over analysing this message).

“It’s exactly as if a long stem of light had outlined a keyhole, and then we all peered, flabbergasted, through that hole.” – (Barthes)

Laura Mulvey argues that this given message in Hollywood classics reflects the patriarchal ideology of its time and is often repetitively stereotypical about gender positions. The spectator looking into the screen may forget he is watching through a perspective there to be seen, this illusion of looking into a private keyhole fulfils the voyeuristic fantasy of the spectator (for example: the opening scene of Hitchcock’s Pyscho, in which the observer peers into a couple’s bedroom whilst they are having sex).

Hollywood reflects the ideology of its time, ‘the psychic preoccupations of the society that produced it’ . Classical Hollywood narrative conveys a powerful blockbuster message, that perpetuates a patriarchal view (the psyche of the ruling power), structures ways of seeing and scopophilic pleasure. Classical H bollywood cinema reinforces positions on gender for the viewers, which have already been causally determined in some way onto the subject since birth. Laura Mulvey wrote ‘Visual Pleasures and Narrative Cinema’ after the beginning of the woman’s liberation movement (in 1917), and she talks of her paper as a document of its time.

Mulvey uses psychoanalysis (rethinking Freud from a Feminist point of view) as a political weapon to find out ‘how the fascination of film is reinforced by pre-existing patterns of fascination already at work within the individual subject and the social formations that have moulded him.’ She discusses the politics of representation of the female figure in Hollywood classical cinema as well as the mechanics of fascination. In doing so, she denounces the objectification of the female, the concept of ‘woman as image’ and ‘man as bearer of the look’ .

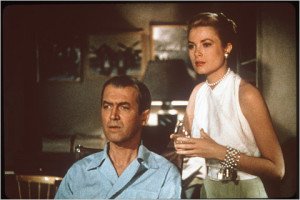

Hollywood classics cater uniquely for the heterosexual male’s pleasure: his fantasy and gaze. The women in mainstream film automatically symbolizes/signifies male desire (or fear ), she becomes a passive or eroticized object of the mise en scene (e.g. the pin up) illustrating ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’. Her role in the development of the story line is needless, contingent; yet she is linchpin to the décor. She stands aside completing it, leaving the labour of action to the more apt and stronger alpha male. She is ‘an element of spectacle’ , distracting the hero by playing on his scopophilic desires (his pleasure in looking) using her seductive looks. ‘Her visual presence tends to work against the development of a storyline, to freeze the flow of action in moments of erotic contemplation.’

The woman on screen is thus an erotic object for the (fetishist and/or voyeuristic) spectator as well as the male protagonist’s visual pleasure. While the scopophilic male protagonist observes the woman with desire, he interrupts his quest to sit next to the spectator, peeping in his turn (e.g. the show girl).

The male protagonist, created in a patriarchal historical context, cannot be seen a sexual object of desire on screen, therefore he embodies the spectator’s ideal ego (see Lacan’s mirror stage ). In the moving image, he is in control: he can do things better than the spectator himself. The spectator (male or female) tends to create a direct complicity with the male protagonist because the story is drawn around the male gaze, his psychological motivations and his point of view. The observer follows him throughout his quest, rendering the male protagonist as ‘bearer of the look of the spectator’. His vision often directs the camera movement, therefore the viewer watches the story unfold from a masculine point of view that controls the outlook of the story. The viewer (he or she) thus identifies with the male protagonist.

Therefore, classical Hollywood cinema reflects the socio-political context of its time, whilst it has the ability to challenge it. Its representation of gender depicts the inequality between men and woman in the twentieth century and women’s struggle in society.

End of part one

Unfortunately, this concludes today’s extract… if you’ve enjoyed reading this as much we have then do check back in at the same time next week for more on Freud, films, and femininity.

Filed under: Film, TV & Tech

Tagged with: advertising, cinema, classic, film, Freud, Hollywood, the image, women

Comments