The Story of Jazz-Funk, with Colin Curtis, Greg Wilson & Mike Shaft – podcast

March 12, 2023

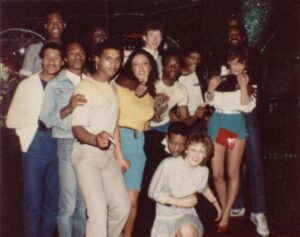

L-R: Greg Wilson, Mike Shaft, Cleveland Anderson, Richard Searling, Colin Curtis, Hewan Clarke, Jonathan Manchester at Tiffany’s 1983. Source: Greg Wilson

Music from Northern England has a vast history, immense impact, and is criminally under-documented. Whilst a few famous artists, scenes and cities get consistently cited, there are many other overlooked moments that tie the cultural tapestry of the North together.

The State of the Arts are proud to be starting a new digital exhibition project focusing on these moments that make up the North’s musical landscape. Through podcast interviews and written pieces, we’ll cover all the scenes that you need to know about.

To start, we’re focusing on the Jazz-Funk era of the late 70s and early 80s that took over the North and Midlands. We enlisted three key characters from the scene that drove its success in Manchester, the North West and beyond – DJs Colin Curtis, Mike Shaft and Greg Wilson.

Our discussion was recorded at Reform Radio, who aired it on 25th Feb. You can listen back to our conversation here, which includes some of the scene’s biggest tracks.

A version of the chat is available on our podcast (see page bottom), with music removed for copyright reasons. A transcript of this version is available here.

***

“Is it jazz? Is it funk? What is it?”

Colin Curtis recalls the early discussions about what to name the new style of jazz-based funk music (or funk-based jazz music) that he and his peers span out to crowds of thousands in the late 70s. It was only after the scene was in full swing that it was labelled Jazz-Funk, by which point it was much more than an intersection of jazz and funk, instead a genre-fluid zeitgeist with an ethos of obsession and experimentation.

From roughly 1976 to 1983, the Jazz-Funk scene gripped the North. People would flock to clubs and tune into radio stations religiously to hear the best Jazz-Funk selections that the DJs influencing the scene could find. It came just after Northern Soul, and just before rave, two of the most celebrated scenes in British music. And despite being just as important to those who lived through it, history has been much more attentive to these other events.

To retell the story of Jazz-Funk, we spoke to three DJs who orchestrated its success. Colin Curtis, one of the country’s legendary club DJs, who was integral to Northern Soul and still DJs regularly, performing his first Boiler Room in 2022. Mike Shaft, whose role as a radio DJ in Manchester brought Jazz-Funk to millions of listeners. And Greg Wilson, who alongside a celebrated DJing career has spent time documenting British music history himself.

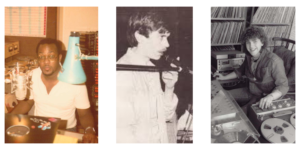

Mike Shaft (left), Colin Curtis (middle), Greg Wilson (right) at Reform Radio

The blueprints for Jazz-Funk were laid by Northern Soul. The soundtrack of the 1970s in the North and Midlands, Northern Soul was characterised by British DJs identifying obscure 1960s motown and R&B records imported from the USA, then playing them out to clubs of locals who would dance all night to this rare exciting music.

Then as the 70s progressed, so did the sound that Northern Soul DJs like Colin Curtis and some of his contemporaries were pushing. Their sets began to feature contemporary music at points in the night when experimenting was permitted.

This was a dramatic departure – Northern Soul had been all about rare, old imports for crowd-pleasing. But the 70s had produced a new breed of black music for dancing that couldn’t be ignored. Gil Scot Heron, Donald Byrd, Herbie Hancock, Lonnie Liston Smith and many more put out higher tempo, rhythmically interesting records in the decade that the DJs felt compelled to play out to crowds. Though not accepted by everyone at the time, the shift in musical style and focus on contemporary artists marked the start of Jazz-Funk’s dominant period.

“It was a changing of the guard,” described Curtis. “We’ve got 14 or 15,000 coming to the All-Dayers… they went from the baggy trousers and the t-shirts, to hawaiian shirts, plastic sandals and whistles”

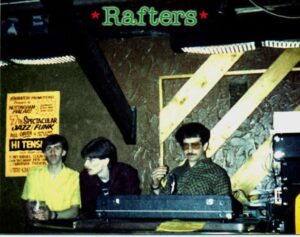

Rafters in Manchester, Colin Curtis (Middle) & John Grant (Right). Source: Colin Curtis

Meanwhile in Manchester, the nightclub Explosion was introducing the funk of James Brown to the likes of DJ Mike Shaft. Shaft took on this new style of black music and played it back to club crowds in Manchester; when Shaft took over the soul show on Piccadilly Radio in 1978, which was listened to by millions of people every day, the same breaking Jazz-Funk Mike was playing in clubs was shared with an even bigger audience.

The appetite for this music was established and the places to find it were being formed. The DJs soundtracked key Northern venues like Clouds, Legends, Blackpool Mecca, Wigan Pier and Berlin, descended upon by thousands of people across the region.

Whilst Jazz-Funk grew in popularity all over the UK, the venues and events in the North West proved its healthiest climate. Wigan Pier and Legends, owned by the same company, had exceptional sound and lighting systems hard to find in the world, let alone the UK.

Legends, Manchester. Source: Colin Curtis

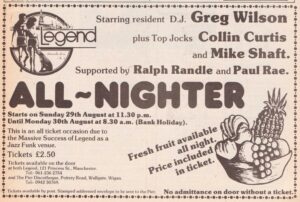

At Legend in 1981, Greg Wilson introduced a unique approach to DJing, with an emphasis on mixing records together, whilst playing examples of a new style called electro-funk. Such steps of innovation were typical of the Jazz-Funk philosophy, helping the scene evolve and stay relevant, whilst boosting the reputation of a club like Legends, which was the defining club of early 80’s Manchester. Legends eventually became the venue known today as Fifth, currently facing closure.

The sheer size of the Jazz-Funk scene and the change in sound in this period was most visible at the All-Dayer events. At the Blackpool All-Dayers at the end of the 70s, Northern Soul – which had soundtracked the Mecca for so many years – was being pushed into the smaller rooms, whilst jazz-funk was finding audiences of 2000-strong.

Legend All-Nighter poster from 1982. Credit: Greg Wilson

All-Dayers provided an extended day-long party that brought in the best DJs around. And with the DJs came the crowds. Coaches of people would flock to events on Sundays and bank holidays from Manchester, Leeds, Merseyside, Birmingham and all over the North and Midlands to experience their favourite DJ. All-Dayers would even feature live act headliners like Lonnie Liston Smith or Roy Ayers, consolidating the love for the newly imported Jazz-Funk that the local DJs had impressed upon these Northern audiences.

Between these venues and events, Jazz-Funk was thriving. It had found its home in the North, and became the dominant club culture sound of the time.

Although not a club, the record store Spin Inn was critical to the scene’s success. Fitting between 6 and 8 people, the Spin Inn would stock up on new music and became the essential resource for the DJs. They would head to the store and take home the best records for sharing on radio shows and club nights – Mike Shaft’s show ‘Taking Care of Business’ on Piccadilly had such reach by this time, that when he picked up records at Spin Inn, he urged the owners to order as many copies as possible ahead of him playing it on air, which was guaranteed to drive demand for the record.

Spin Inn Records, Manchester. Source: Colin Curtis

There were only a few record stores in the country like Spin Inn. And they were a vital organ in the local music ecosystem, connecting new tracks to their main marketing tool – the Jazz-Funk DJ – and the audience that would hear the record, dance to the record and buy the record to bring commercial benefit back to the artist.

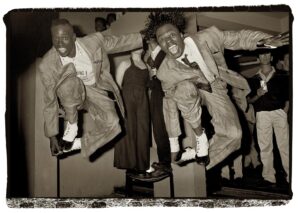

The audience for the Jazz-Funk scene was uniquely diverse. Whilst Northern Soul had a white audience, jazz-funk attracted young people of all backgrounds. Dancing was an essential part of the scene – and not dancing as it’s done today. Dancing was an expression of individuality, and the more energetically creative the dance, the more special you were. Groups of Jazz-dancers in crews would battle it out at events. Dancing, performing, was intrinsically tied to identity.

The dedication of the Jazz-Funk audience to the scene meant thousands were willing to travel miles across or outside their region, to dance at as many events as they could. Colin Curtis recalls giving someone a lift from Wigan to Keele services, so they could get back to Birmingham, and asking him, “What are you going to do with your life?”. They’re response: “Well, I’ll just be dancing all my life”.

Foot Patrol at Hacienda. Credit: Ian Tilton. Source: Greg Wilson

This sonic era would not have been the same without the exceptional music released at the time. At the start, the departure from the strict motown oldies to play contemporary soul was a controversial move, but the quality of new music being produced at the time couldn’t be ignored by the DJs – as Colin Curtis explains, the scene’s success was thanks to the “vast amount of intelligent music coming out in this era, most of which has stood the test of time”.

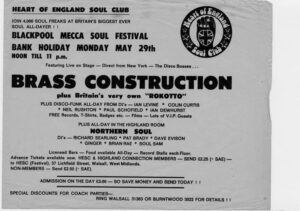

Jazz-funk profited from the reputational decline of disco, at the hands of Saturday Night Fever, which had made it commercial, crass and “un-cool”. DJs instead turned to jazzier funk records, or funkier jazz records, coming fresh out of the states from the likes of Donald Byrd, Lonnie Liston Smith, Gil Scot Heron, Roy Ayers, the JBs and many more. Brass Construction, whose seminal debut album topped charts upon release in the mid-70s, exemplified the speed and the sound of jazz-funk.

Poster for Brass Construction, Blackpool Mecca. Source: Colin Curtis

Brass Construction influenced important artists from Britain producing their own brand of funk, such as Hi-Tension, Light of the World, Level 42 and Incognito. These artists were being played out by the jazz-funk DJs and performing at the all dayers, bringing them into the Jazz-Funk fold and signalling the birth of Brit-funk.

As the decade progressed, Jazz-Funk’s peak eventually passed, giving way to new sounds and styles that culminated in the late 80s rave era.

With rave came the dissolution of audience dancing as it had been seen during the Jazz-Funk years. Clubs like the Hacienda became too packed with white locals to fit the dancing black audience that required space. This of course altered the demographic of the Hacienda and of rave, which began being properly documented from 1988 onwards, so evidence of its early black audience is scarce.

Wigan Pier Jazz-Funkers with Rose Royce members 1981. Source: Greg Wilson

The sound was changing again, as it had from northern soul to Jazz-Funk. By the mid-80s, electro was seeping in thanks to DJs like Greg Wilson, and Colin Curtis was bringing Chicago house to the masses. But this change in sound was in keeping with the jazz-funk philosophy. Whilst you had the quintessential sound of Brass Construction, it was a fluid genre which allowed DJs to play reggae, Latin and all sorts in their sets. Mike Shaft insisted on sharing slots on his Piccadilly show with other DJs who could hone in on one style for 15 minutes. The open mindedness of the DJs was what helped the scene to keep evolving, and eventually branch into new dominating scenes and sounds.

Like any great musical movement, it was of course the places, the punters, the imports that elevated it. But at the centre of the scene were the people making it spin. The DJs, like Colin, Mike and Greg, a small selection of experts responsible for curating the events and tracklists that tied everyone involved together.

The willingness of the DJs to take risks with merging sounds, expanding beyond the genre-d words ‘jazz’ and ‘funk’, making room for Afrobeat, Latin, soul, electro and more, was their guiding ethos, and made them push their audiences into new directions whilst making sure they kept dancing.

Mike Shaft, Colin Curtis, Greg Wilson. Images from Greg Wilson.

The influence of Jazz-Funk has been immense, informing British scenes since from rave, to acid jazz after it, to the British jazz explosion of today. All the prominent people growing up in this era, affected by the variety of Jazz-Funk, such as Gilles Peterson, who consciously or subconsciously shares its ethos, best demonstrated by the We Out Here festival (headlined this year by Brit-funk icons Cymande).

All these years later, do the architects of the Jazz-Funk scene appreciate their impact? “Hell yes!” says Mike. “If we the DJs didn’t have the knowledge, the scene would not have happened.”

Jazz-Funk may be eclipsed somewhat in our historic memory by earlier or ensuing scenes, but it was essential for the evolution of British club culture and musical identity. As time passes, the significance of what Colin, Mike, Greg and all their contemporaries achieved will only become more evident.

***

Tracklist from our recorded conversation:

The Message, by Cymande

The Bottle, Gil Scot Heron

Movin’, Brass Construction

Come With Me, Tania Maria

Dirty Talk (USA Connection Instrumental Mix), Klein & MBO

Love Money, TW Funkmasters

Nightlife, Blair

Central Park, Chic Corea

Space Princess, Lonnie Liston Smith

For more information on Jazz-Funk, check out some of Greg’s writing here.

Filed under: Music, SeeHearRead, TSOTA Podcast

Tagged with: Blackpool, British music, club culture, clubbing, Colin Curtis, dancing, dj culture, djing, electro, funk, Gilles Peterson, Greg Wilson, jazz, jazz dancing, jazz-funk, manchester, Mike Shaft, music, North West, Soul, Wigan

Comments