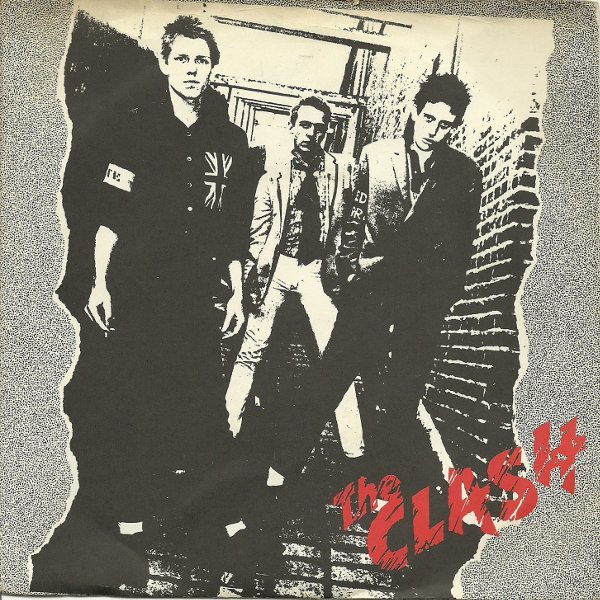

The Story of ‘Selling Out’: major labels, independence and The Clash

‘Remote Control, the Clash, 1977

The choice to sign to a major label or not was central to selling out debates for punk and indie scenes of the 1980s and 1990s. Bands who were seen to turn their backs on independent scenes by signing a contract with a major label were branded sell-outs and dropped by some earlier fans. But major labels had not always been viewed as the corporate enemy and independence in production and distribution was a relatively recent development. The story behind the Clash’s 1977 ‘Complete Control’ single sheds light on growing distrust of major record labels: the perceived threat to artistic freedom eventually blossomed into successful networks of independent labels for the punk scenes and descendants of punk scenes that followed.

Early examples of independent record labels were largely unconnected to the politics of art and commerce that underline selling out debates. In the 1960s, labels like Joe Meek’s Triumph or Andrew Loog Oldham’s Immediate operated much like, and held the same values as, the majors. While some independent labels formed to accommodate artists considered too controversial, risky or unprofitable for the majors, a successful independent label could expect to be purchased or otherwise supported by a major without objection. Even early punk groups held no ideological opposition to major labels: the Sex Pistols and the Clash were both signed to major labels, and while Sire was technically independent when it signed the Ramones in 1975, it had major label distribution deals and was acquired by Warner Bros in 1978. However, the control major labels were believed to assert over output left some musicians and fans wary.

The case of Clash songs ‘Remote Control’ and ‘Complete Control’ encapsulates the struggle. As Jon Savage describes in the excellent and richly detailed ‘England’s Dreaming‘, in 1977 CBS went against the band’s wishes when it released the track ‘Remote Control’ as a single. ‘Remote Control’ was unsuccessful in charting but successful in raising questions about the artistic independence specified by their contract. The group responded to the situation with the song ‘Complete Control’, released on the US version of their debut album, and featuring the lyrics “They said we’d be artistically free/ When we signed that bit of paper/ They meant let’s make a lotsa mon-ee/ An’ worry about it later”.

Resulting discussions about major label power and control galvanised many musicians to seek out alternatives: as David Hesmondhalgh and Leslie Meier argue, ‘the debate about such “selling out” helped to fuel the growth of a new generation of labels, inspired by the Do It Yourself ethos of punk’ (2014: 98)/

Following punk’s peak, many musicians and fans took up the bid to release records independently and, by the 1980s, independent labels were a key component of multiple scenes stemming from early punk. Some independent artists voiced explicitly anti-corporate values and located independence (of music-making as of thought) as central to identity, and labels like Rough Trade and Factory in the UK and K and Dischord in the US offered a natural home.

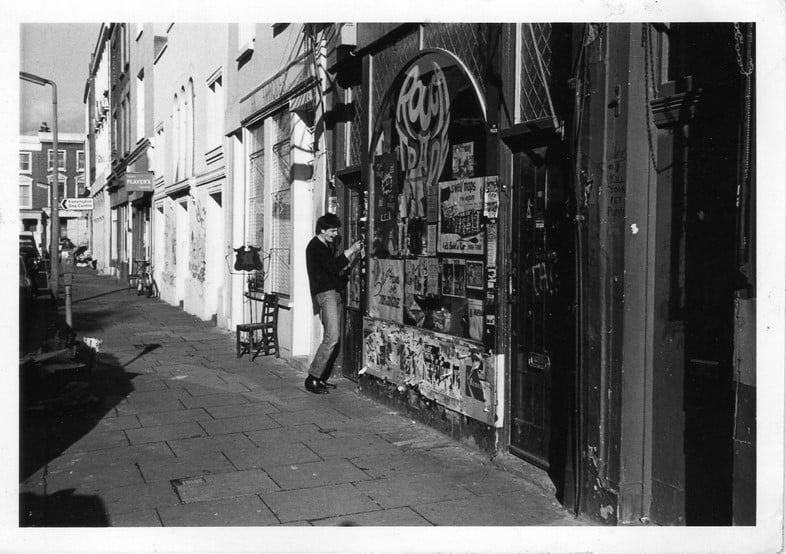

Rough Trade Records

While less accessible sounds produced by some scenes (for example, US hardcore) made mainstream appropriation unlikely, the more successful sub-genres of punk and indie found themselves courted by major labels under marketing terms like ‘alternative’ or as ‘indie’ but with the connection to independent production severed. The examples of Nirvana and Green Day, whose leaps from independent labels to majors resulted in global success (alongside accusations of selling out), led to a signing bonanza. Formerly independent music was incorporated into major label rosters and distribution so thoroughly in the 1990s that the categories ceased to make sense, and debates about ‘signing’ receded. Even so, cultures of independent music making around the world continue to highlight the value of doing it yourself in order to avoid the complete control of a major.

This is the second in a series of posts about the concept of ‘selling out’ in popular music culture in advance of the August publication of ‘Selling Out: Culture, Commerce and Popular Music’ by Bloomsbury. You can read the first post, which considers popular music, art and the Who, here.

Follow @bethanylklein on Twitter and register for the online book launch here: ‘Selling out – book launch. Culture, commerce and popular music’, on the 6th August.

Filed under: Music

Tagged with: book, book launch, Commerce and Popular Music, Complete Control, england's dreaming, john savage, major labels, music, punk, selling out, Selling Out: Culture, Sex Pistols, the clash, the ramones, warner bros

Comments