Credit: Philippe Le Tellier

A 1965 article in Melody Maker described the Who as ‘linking their image with what they call Pop Art’. According to the music paper, ‘They describe their current chart success, “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere”, as “the first Pop Art single,” and they have started designing their own Pop Art clothes’. The Who’s claim to Pop Art was important for two reasons: first, it made a connection between popular music culture and the established art world, suggesting that we should treat popular music as seriously as any other art form. Second, it introduced to popular music an ambiguous relationship with commerce borrowed from the Pop Art movement.

British Pop Art was rooted in the 1950s work of the Independent Group within the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, artists responding to the growth of consumer culture and development of commercial design, influences which began to feature in their art. Through the lens of Pop Art, advertising, news and youth culture were all potential material for art. Were these artists offering a wry commentary on consumerism? Or was their work a genuine embrace of commercial culture? The elusive position of Pop Art was part of its interest.

By the mid-1960s, Pop Art and popular music had entered into a genuine relationship, rather than the latter simply providing material for the former, as with Andy Warhol’s 1963 painting of ‘Triple Elvis’. Warhol’s design for 1967’s ‘The Velvet Underground and Nico’ was followed by experiments in album covers by artists drawing on innovative design techniques: the cover of the Beatles’ ‘Sgt Pepper’ (1967) was designed by pop artists Peter Blake and Jann Haworth and pop artist Richard Hamilton designed the Beatles’ ‘White Album’ (1968). The mutual appreciation between pop musicians and pop artists was observed at the time by critic George Melly and in 2014 was wonderfully documented by art historian Thomas Crow in ‘The Long March of Pop‘. One result of such intermingling? Pop music was given a seat at the artistic table, able to draw from and be evaluated through values associated with art, including the concept of selling out.

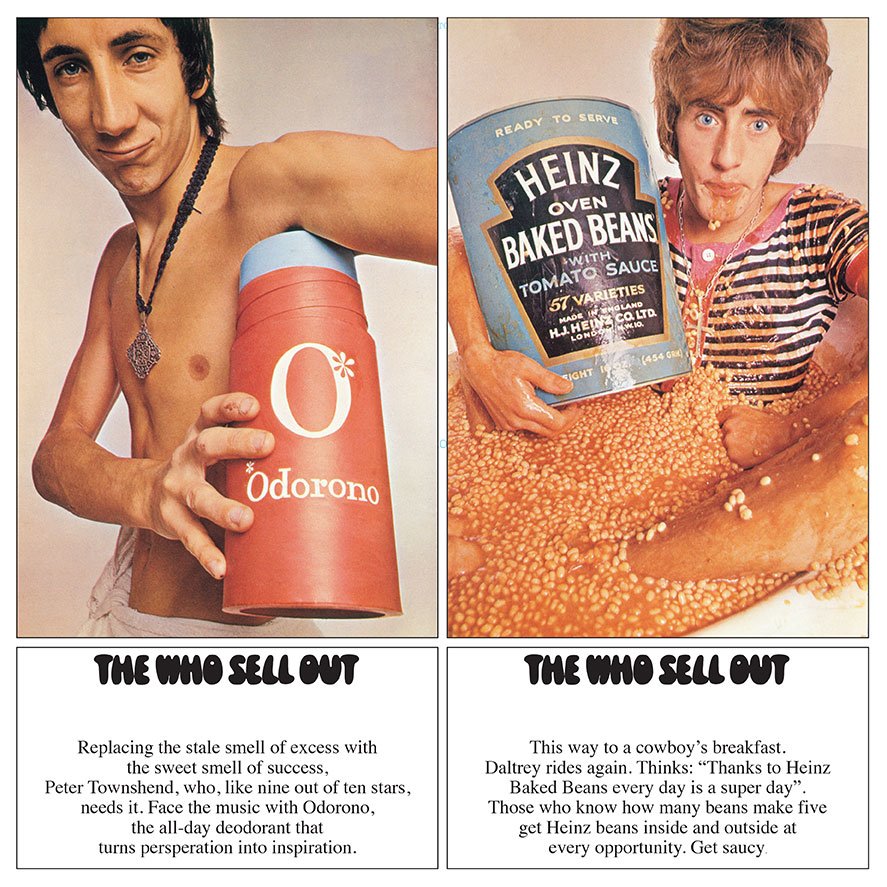

The idea of selling out, typically understood as compromising values for financial gain, was the focus of the Who’s 1967 album, ‘The Who Sell Out’. Presented as a pirate radio broadcast, the album played with commercialism through its concept and its cover. Townshend composed commercial jingles to separate the tracks and the cover featured the band members in four panels of ads for real and fictitious products. The album has been described by music writers as a “pop art masterpiece” and “rock’s greatest example of pop art“. And like other examples of Pop Art, the album’s perspective on commercialism is ambivalent and contradictory.

Interactions between pop music and pop art in the 1960s left a legacy for future musicians and music scenes, including in terms of what selling out might look like. As with Pop Art, popular music doesn’t claim to exist outside commercialism, but that doesn’t mean anything goes. The Who’s performance of selling out highlighted some of the real actions that could attract the accusation: product placement, brand sponsorship, making music for advertising. What counts as ‘selling out’ in popular music has varied across decades and genres, but it is unlikely to have become a meaningful concept without the mid-1960s flirtations between pop musicians and pop art, which helped musicians, listeners and critics to understand popular music as art, rather than mere entertainment.

This is the first in a series of posts about the concept of ‘selling out’ in popular music culture in advance of the August publication of ‘Selling Out: Culture, Commerce and Popular Music’ by Bloomsbury. Follow @bethanylklein on Twitter and register for the online book launch here: ‘Selling out – book launch. Culture, commerce and popular music’, on the 6th August.

Filed under: Music

Tagged with: art world, Beatles, Bloomsbury, commercial, Culture, movement, music, pop art, selling out, The Who, Warhol

Comments