“The Wrong Sex” – Rediscovering Fanchon Fröhlich: The Unsung Abstract Expressionist

April 24, 2023

The best thing about walking into an exhibition of an artist you’ve never heard of is that it opens up new territory – especially when the artist is described in the blurb as “forgotten”, which usually indicates they are worth remembering. So it proved to be with Fanchon Fröhlich (1927-2016). Not forgotten by her many friends, but by the art world to which she dedicated her wide-ranging creativity and curiosity.

Fanchon Fröhlich lived a life that defied categorisation and containment, so it might seem reductive to do so now. But some of the labels that can be attached to her are necessary to convey her polymath talent and passions. Here are a few: abstract expressionist painter, printmaker, philosopher, scientist, Buddhist and Bohemian.

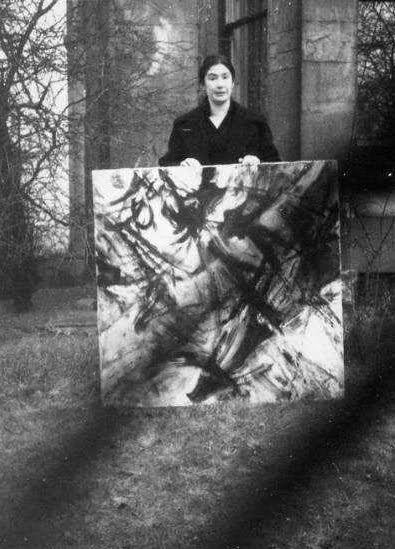

Fanchon painting. (Image Property of BADA)

The exhibition “Fanchon Fröhlich: The Wrong Sex”, aims to directly address how she was overlooked in her lifetime and to open up her impact across artistic, scientific and philosophical spheres. Fanchon, née Aungst, from Iowa, USA, arrived in Liverpool in 1949 where she was introduced to the scientist, Herbert Fröhlich, who was Liverpool University’s Chair of Theoretical Physics. They married a year later and lived in Toxteth for the rest of their lives.

The title of this exhibition makes reference to the one categorisation Fanchon could do little about – that of being a woman. She was told that the main reason for not being taken seriously as a scientist or an abstract expressionist painter was that in those male dominated worlds she was “the wrong sex”. Thankfully, the times they are a changing (to riff on Dylan’s lyrics) and the aim of this exhibition is to posthumously reverse that prejudice.

The opportunity to do so has come about largely thanks to Fanchon herself, who never threw anything away and then had the foresight to bequeath her archive to another artist, her friend Terry Duffy, and the charitable arts organisation he founded in 1986, BADA (The British Art and Design Association). When I spoke to him, Terry explained that the Toxteth house, where Fanchon lived for decades, was overflowing with her life’s work, much of it in a ruined state, such that he felt it was only another artist who would recognise the importance of it all and have the empathy not to bin the lot. Many of the things stored in the damp basement were lost but there is still a phenomenal amount that BADA has saved and which is now professionally archived.

In collaboration with the Exhibition Research Lab (ERL) at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), where this show is held, the rare display of archival documents makes this exhibition more than a presentation of Fanchon’s paintings, prints and drawings. This is a life exposed. It can make for an unsettling experience – the viewer becoming voyeur, particularly when leafing through her journals and sketchbooks. These reveal intimate details of her life and loves in all their complexity and profundity of thinking and philosophising.

Fanchon Frohlich Installation View (Credit: J Schofield)

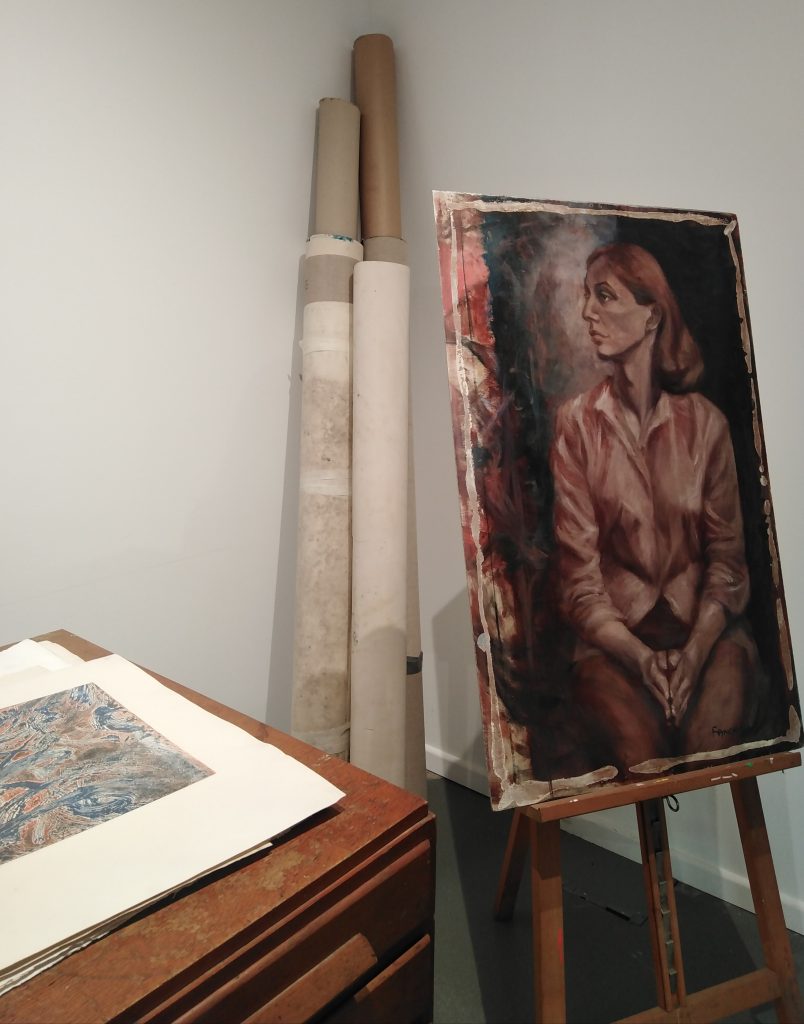

The centre of the spacious and bright room is filled with large, vibrant abstract paintings hung back-to-back from the ceiling, much as they were in her studio. These exemplify the type of abstract expressionism Fanchon favoured – that of dynamic, spontaneous brushwork and mark-making. Her process also involved what became known as ‘action painting’, through its performative nature of dribbling or splashing paint onto the canvas rather than directly applying it – a technique immortalised by Jackson Pollock. Other artists working at the time, such as Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, were also classed as Abstract Expressionists but produced compositions using blocks of colour. More examples of Fanchon’s works on canvas are leaning against the walls; others are rolled up and standing in the corners, next to paintings on easels she made of Beryl Bainbridge and her husband, Herbert.

In shallow display cases, here and in the approaching corridor, there are examples of her powerful charcoal drawings, her sketchbooks with illustrations of how she scientifically worked out her abstract designs, and photos of her at all stages of her life. On shelves are key books from her extensive library showing her wide-ranging interests. Nearby on a plans chest are piles of her prints, with the original etching plates also on show. On one wall, Fanchon has been rather spookily brought to life, through a huge projected avatar of her transitioning from child to older woman, smiling out at us.

Dr James Schofield, one of the curators of the exhibition, explains that “The Wrong Sex” will not be a static presentation: “Much like the artist and her own way of working, the display will be dynamic and changing throughout the lifespan of the exhibition”.

A description of her work written in 2008 by friend and poet, Jeremy Reed, is also borne out in this current exhibition: “Her work, always celebratory in tone and driving in energy, is the unstoppable example of an artist working with courage at the edge, and one who is prepared to accept all experience as subject matter for art”.

Painting by Fanchon of Beryl Bainbridge (Credit: Lorraine Bacchus)

Fanchon applied her adventurous experimentation to all aspects of her life. For decades, she and her husband were at the centre of what became known as Liverpool’s ‘Bloomsbury Group’, i.e. Bohemian. The eclectic mix of visual artists, distinguished scientists, writers and composers who made their way to the rambling house on Greenheys Road makes for extraordinary reading and imagining. They included Erwin Schrödinger, John Cage, and Liverpool author, Beryl Bainbridge, who was a life-long friend of Fanchon’s. The friendship between the two women survived various ups and downs, as they say, including Fanchon’s affair with Beryl’s husband, the painter Austin Davies, who had been her tutor during her postgraduate degree at Liverpool Art College.

She seems to have had a homing instinct that led her to the greats in whichever area she chose to expand her artistic practice. It’s all so easy now with the internet but back in the 1960’s this wasn’t the case. Yet she was a consummate networker, finding her way to Paris, for example, to study printmaking with William Hayter at his legendary Atelier 17. During this time she exhibited her abstract prints alongside such giants of the time as Marcel Duchamp and Joan Miró. She was right there amongst them all and respected enough to exhibit with them. Prior to her time in Paris, Fanchon became part of the famed St Ives artist community in the late 1950’s, where she was invited to work alongside the renowned post-war abstract painter Peter Lanyon. As Terry Duffy explains, this was a crucial time for Fanchon: “Lanyon, the St Ives set and, I believe, the introduction to a more free international abstract expressionism became a stepping stone to Paris and beyond”. This connection between Fanchon and Lanyon led to his major mural commission, “The Conflict of Man with Tides and Sands”, at the University of Liverpool, which can be seen in the Department of Civil Engineering.

The organisers hope that this multi-faceted retrospective exhibition is the start of an appraisal of Fanchon’s work and her place in the Western canon – as well as the possibility that it will inspire a new generation of artists.

‘The Wrong Sex: Fanchon Fröhlich’ is on show until 4 May 2023 at the Exhibition Research Lab, John Lennon Art and Design Building, LJMU, Duckinfield Street, L3 5RD.

© BADA (The British Art and Design Association)

Filed under: Art & Photography

Tagged with: abstract, art, artist, BADA, creative, curiosity, exhibition, Expressionism, forgotten, liverpool, painter, philosopher, remembered, scientist, wrong sex

Comments