This Is Not A Museum

December 2, 2015

Many museums across the UK allow the viewing public limited access to the facilities that house their stored collections. For the Birmingham Museums group, this means supervising scheduled visitors throughout a 1.5 hectare warehousing site on the last Friday of every month.

Should you wish to visit on one of these final Fridays, be forewarned that only two hours from 1.30pm – 3.30pm are allotted for your absorption of the visible portion of 80% of the city’s stored collections, and booking is required. Alternatively, private group tours can be arranged. Or, bide your time till the next of the Museum Collection Centre’s biannual open days, an option which affords ample allowance for ambling between the hours of 10am and 4.30pm, toll-free.

In 2015 the second and last of the year’s free open days took place on the 12th of September, and this writer took the liberty of dropping in. The Museum Collection Centre (MCC) had made provisions for the purchase of food, for the special entertainment of children, and for semi-scheduled transport to and from a bus stop outside SQ3 Lloyds House near Snow Hill train station. But it was a warm and breezy early-autumn day, so I walked the mile or so from the town centre to the edge of Nechells to take in the sight of Brummagem’s still-churning, gleaming refurbishment of millennium point.

Having recently undertaken some fascinating seasonal work at a packing warehouse, I was looking forward to immersing myself in a warehouse of an entirely different order. The MCC nestles amongst other industrial buildings and I chose to walk a winding path, so I got slightly lost. Briefly I stood watching scavenging birds through a mesh fence that ringed a recycling depot stacked with rotting, discarded plastics, which brought me swiftly back down to earth.

When I finally entered the MCC I struggled at first to make a value-based distinction between the plastic artefacts being carefully kept there in locked cabinets, and the plastic I’d just seen being pecked at by crows. I could not find the sense of reverent leisure I had been searching for, and no boundary emerged between the warehouse as a workplace and the warehouse as a museum.

In the text Is a Museum a Factory?, Hito Steyerl draws parallels between the histories of cinema, the museum, and the factory in order to cast the space of film and of the museum back into a realisation of their industrial existence as a site of social production where “even spectators are transformed into workers”.

Steyerl makes the following distinction: “While the classical space of cinema resembles the space of the industrial factory, the museum corresponds to the dispersed space of the social factory.” Positioning the dictatorial sovereignty of Boris Groys’s installation artist as a standard mode of production “in any social factory”, Steyerl’s text reiterates that the labouring multitude inside the bourgeois public sphere of the museum may be imagined as a cacophony of competing sovereigns. In this diagnostic, the sovereigns that are involved in museum production each labour from their respective subject positions of “curators, spectators, artists, critics,” architecture, and objects.

In historical or heritage museums the workers responsible for the initial production of the curated objects are often long deceased, nameless, or in some other way lacking agency of the kind that may be functionally ascribed to the rhetorically unalienated contemporary artist. In a curated historical archive, the interpretive agency of the camera-wielding visitor is limited by the eminent authority of the historian-curator. As such, the sovereignty of the traditional museum curator in charge of historic collections can appear to remain relatively shielded from the co-curational impulses of agents within their charge.

Not so in the warehouse. This is a museum archive that has withdrawn from the curator’s hand; the working space of the MCC buries any semblance of the curator’s dictatorship. On an open day or a tour, the material conditions of the main museum’s existence are the exhibit on display, whilst the Institution behaves like Groys’s Installation Artist who is permitted to try temporarily imposing their sovereignty on the productive, ostensibly public, space. The act of opening the bowels of the museums to public view presents the working space itself as spectacle.

A storage area, a space arranged by procedures that arise from the institution’s need to reproduce itself by ensuring the longevity of the museum and the objects it collects. As it often does, the Birmingham Museums group provided restoration workers on-hand to inform the public of what procedures are necessary to maintain its archive.

The warehouse is yet an aspect of the factory. The subject-position which manifestly produces the law by which industrial space is arranged, and so assumes the role of sovereign, is capital as “dead labour“. In the workplace, any human sovereignty can be subsumed by semi-autonomous logistical procedures, by institutional necessity. The prevailing law of the warehouse is that the working space operates under whatever dehumanised logic suits capital’s requirements.

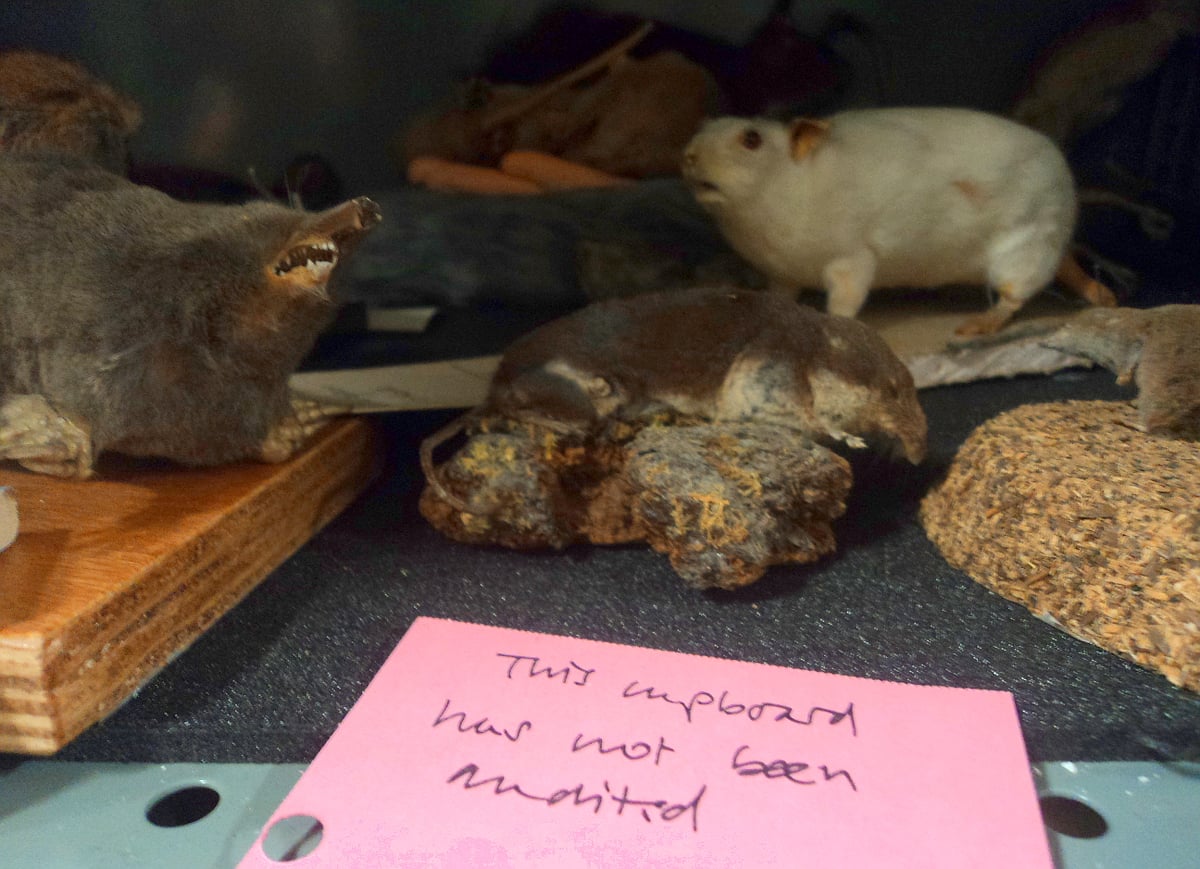

In the Museum Collection Centre, the caretaker institution is compelled to warehouse cultural capital at maximum efficiency. The institution operates under the law that it must store the objects that it captures even when there is currently no dedicated public gallery space in which these objects can succumb to curation. As such, objects at the MCC largely appear in a chaotic assemblage of colliding time periods, origins, and functions. Without a strong curatorial hand, the unguided visitors project their own lines of association, and many visitors were brightly discussing objects they had previously experienced in their own lives.

Parallels between the museum and contemporary industrial sites of production beam out at the spectator from the impersonality of the fittings: the crude metal grille protecting the small object lockers, the towering warehouse aisles, the fenced-off forklifts and restoration workstations. By proximity, parallels also appear between the varying types of prematurely antiquated machinery that are housed here: the machinery of war, of culture, of industrial production, of the home, and of the archive. But this space resists orientation around the aesthetic sensibilities or whims of a visiting gaze.

Utilitarian hazard signs, the physical invisibility of most of these stored objects, the fittings – all produce a disciplinary sensation which echoes that of the alienation given to labour in an industrial warehouse. A sense of enclosure, of agency’s limit. The sovereignty of the objects’ value as protected capital reigns far above the sovereignty of any democratic demand that may arise from the needs or desires of the visiting, volunteering, and waged public which labours as the living presence here. Visitors are asked not to touch the objects – physical integrity is at stake.

Visitors to the Birmingham Museum Collection Centre must suspend their expectation that a museum will attempt to consistently define and narrate the meaning of the objects it displays, and that it will do so for the immediate cultural betterment of the viewing public. By placing these objects in storage the museum has already positioned them in a state of exception. After all this is not technically an exhibition, and, in the words of a young child overheard in the Small Objects Room: “This is not a museum.”

When the ordinary state of things is suspended the exception can fulfill its role as delineator of the rule [1] , just as différance acts to define convention. In order for the institution to make the assertion that the museum operates for the benefit of the public, it is necessary that somehow the museum and its ordinary functions be temporarily positioned elsewhere, so that their sovereign characteristics might safely be asserted here.

By making public the private space of the museum’s storage areas a plea is entered: that the museum operates benevolently on the public’s behalf, and that the museum as an institution must be allowed to continue to sustain itself from within the implicitly vital subject position it currently occupies. In this act of disclosure the museum’s visitors, the museum’s staff, and every object it houses are all drafted into an abstract assertion of intrinsic value. In the Age of Austerity, the bourgeois heritage museum must insist on its sovereign right to exist.

As the visitor snakes between the aisles around these modest industrial storage facilities, the enduring human presence of museum curators can of course still be felt. Relics of past exhibition displays are scattered amongst the horde, and information regarding the provenance or nature of certain articles is occasionally provided, by some idiosyncratic lottery. But, there remains an inadequacy or lack which allows for the institutional impetus towards public benefit to be framed here as a meek, precarious animal, plaintively underfunded, stuffed by volunteers.

[1] For an overview on the sovereign and the state of exception, see: Giorgio Agamben, ‘The Messiah and the Sovereign: The Problem of Law in Walter Benjamin’, in Potentialities, p.160

Filed under: Art & Photography, Politics

Comments